MARIAN VAN EYK McCAIN – GREEN LIFESTYLE, GAIAN SPIRITUALITY & WRITING BOOKS

I interviewed Marian Van Eyk McCain who, on her Elderwoman site, discusses women aging and ‘sage-ing’. Marian describes her women-centred writing as “An advertisement for

In the Rhyme of the Ancient Mariner, the mariner touches the shoulder of the wedding guest, beginning his story with “There was a ship.” When the wedding guest objects, the mariner hypnotises his unwilling subject with a fixed and glittering stare.

Using a similar but much lighter technique, the great master of hypnotherapy, Milton H Erickson, developed the ‘handshake induction’ designed to produce a gentle trance. Erickson would distract his client at the start of a consultation by gradually withdrawing his hand and touching the wrist so gently that his subject couldn’t quite tell when the contact ended.

In both cases the goal was for the subject to pay attention to hints and suggestions normally passed over, and focus uncritically on a single train of thought. In the process, the subject would discover hidden truths about the self or personal experience.

The story of my cross-dressing was similar.

It developed from an ‘interrupted move’ – the dream-feel of a dress worn in a wood – and the long-term memory (still with me today) of heightened flow and wellbeing. Dressed up, I was nicer, fuller, more glamorous and in touch. I’d come across something special, I was fascinated, and wanted more.

After that there were whispers, voices in my head telling me to try it, to go back to the wood, to do what I liked and find out where it led…

Years later, having been outed by the papers, I was on the corridor of a London Comprehensive saying, “Why not?” to a girl who’d asked me to explain. I was married, with children, I was political, educated and a survivor-teacher. My reply was intended as a challenge, turning the tables, but in some secret part of me I understood what she meant.

From the start I’d called it my own funny habit. There were various ‘explanations’, words and phrases I’d used in my internal arguments and struggles not to ‘do it’ – it didn’t have to touch me, I was going through a phase, it was nothing really, an act I’d developed that really wasn’t me. I’d reasoned and protested, tried bullying myself, but ended giving in. And the habit became obsessive, beginning with a petticoat taken from a drawer, a small piece I liked and viewed in the mirror like a woman in a shop, then all sorts of underwear with skirts and blouses, squeezing into heels. That was when the house was empty, ‘going the full way’ when my parents were out shopping. More often I tiptoed across the landing to sneak-thief an item and take it back to bed. In the dark I was hidden, I’d a girl in there with me, I was lucky to have her and no one could touch us. And afterwards, when I ghost-walked the carpet to return my item, I prayed my parents wouldn’t hear me.

In fact I prayed quite a lot when they were out, splitting myself into angel and devil and getting red-faced and shouty, pleading for the strength not to do it. I was in the danger zone, the route ahead was dark, but a Faustian curiosity drove me on. Looking back now, I can feel the loneliness. This was unheard-of, I’d no points of reference and, like the mariner, the weight of my secret marked me out.

I was lucky not to get caught. Aversion therapy, using pictures and electric shocks, was the ‘treatment’ at the time. It only took one item misplaced or a tell-tale stain, and the questioning would begin. So although it didn’t happen, I’ve a film in my head of my parents’ disbelief, their shock and disgust, the hospital visits and the silence that would follow.

Later I discovered Robert Stoller’s ideas of primary femininity and the long history of transgendered people, but I still knew when I answered the challenges at school that wearing women’s clothes had its stigma. Films like Psycho had made sure of that. At best it was considered silly, a kind of regrettable, narcissistic, pumped-up self-indulgence. “Is it really necessary?” was the question behind what I’d been asked. And the girl had asked it in a tone that brought back my parents saying “You’re not like that.” There were other voices too: cynical colleagues who saw me as naïve, that I’d given the press their story, so what did I expect? Or puzzled, well-meaning friends who were worried, advising caution with world-weary smiles. Then there was the voice of social responsibility: what about my children, how did they feel, and did my wife really let me do that? The finger was pointing and I was to blame.

At school I didn’t talk about history or respecting choices or understanding difference. I couldn’t really. It wasn’t straightforward, there were so many stereotypes, and time was too short. And like an actor in the spotlight I had to play my part, be authoritative and deliver my lines. But in hindsight, if I had to explain, speaking as my own advocate, this is what I’d say:

Cross-dressing is part of a spectrum, it has its own place and belongs to the rainbow.

So why not enjoy it?

Next week, the story of my cross-dressing concludes with MY OUTING Part 5 – MY STORY.

ABOUT LESLIE TATE’S BOOKS:

I interviewed Marian Van Eyk McCain who, on her Elderwoman site, discusses women aging and ‘sage-ing’. Marian describes her women-centred writing as “An advertisement for

I interviewed artist, writer, curator and educator Sarah Chapman who led and directed The Arts Institute in Plymouth. Sarah tells the story of working with

I interviewed Ray & Bev Langton, team leaders and founder members of Shrewsbury Morris, where people “Dance, Laugh, Have Fun, Repeat.” Bev & Ray talk

I interviewed Tamsin Lillie CEO of Medic to Medic, a charity that supports trainee health workers in Africa. Tamsin, who studied at London School of

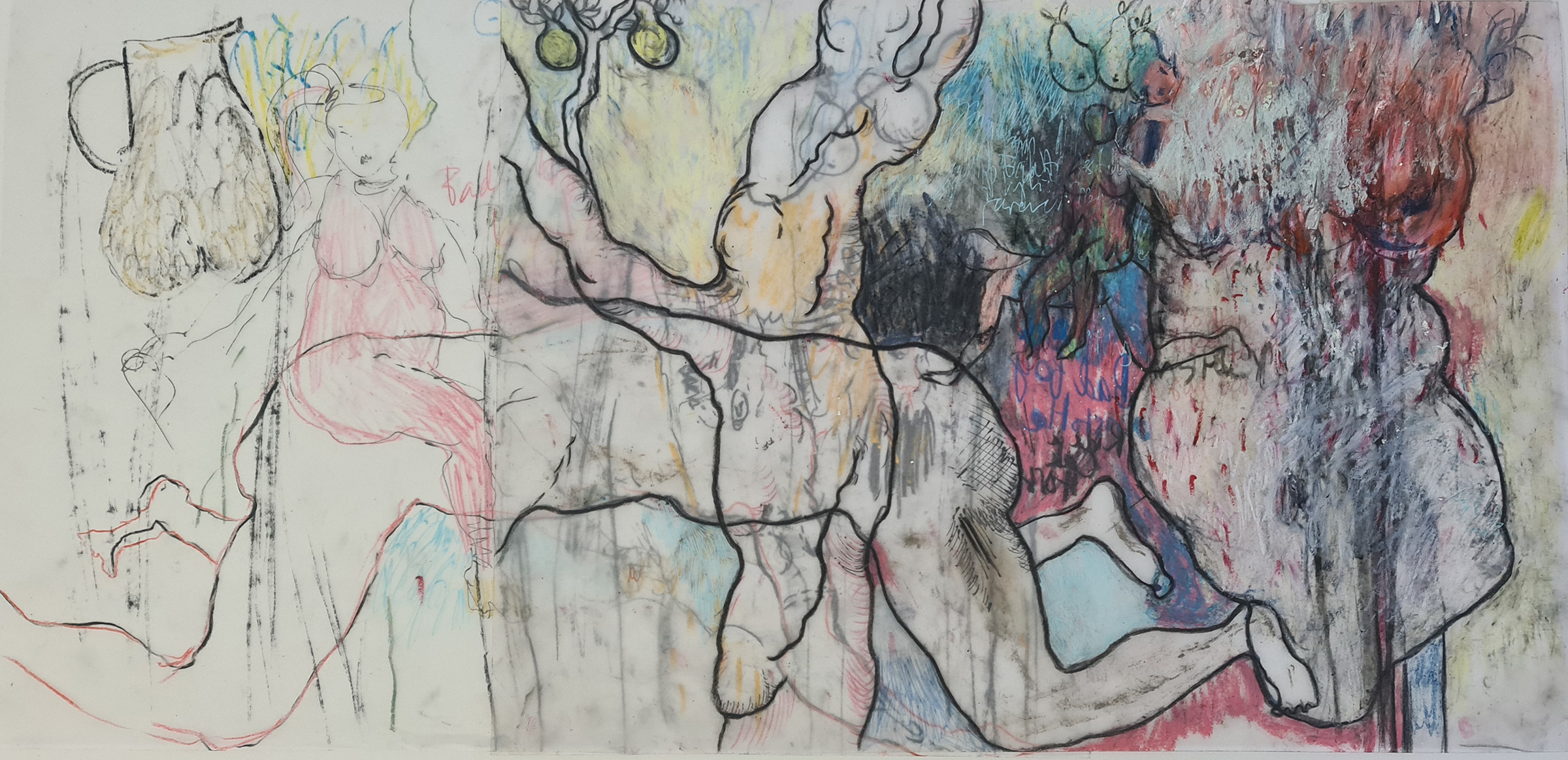

I interviewed artist, researcher and poet Becky Nuttall who creates powerful images around women’s identity. Becky, who comes from an artistic family, sometimes collages parts

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |