SARAH ROSS-THOMPSON AND THE ART OF COLLAGRAPHED PRINTS

I interviewed artist Sarah Ross-Thompson whose exceptional Collagraphed prints use fabrics, lichen, porridge and string to create images of the dramatic Scottish Highlands where she

I interviewed international poet and translator Mark Statman about Volverse/Volver, his 14th published collection. Mark, who has won national arts awards, is Emeritus Professor of Literary Studies at Eugene Lang College of Liberal Arts, The New School, NY, and now lives in San Pedro Ixtlahuaca and Oaxaca de Juárez, Mexico. Part One of the interview covers the relationship between his new ‘third voice’ collection Volverse/Volver and Exile Home and Hechizo.

Mark’s Wikipedia entry says, “His writing has appeared in numerous anthologies and reviews. Statman is a dual national of the United States and Mexico.”

Leslie: Why did you call your latest poetry collection Volverse/Volver?

Mark: Volverse in Spanish means to become. Volver is to return. I was trying to get at a bunch of different ideas at the same time.

The first had to do with a big picture of where this book stands in relation to the first two Mexican books, Exile Home (Lavender Ink, 2019) and Hechizo (Lavender Ink, 2022). I wrote Exile Home out of the sense of excitement we felt, I had felt, at the move Katherine and I made to Mexico in 2016, as well as facing the death of my father. It was an excitement that because of being in exile and having exiled ourselves from the US, I somehow sensed I had also come home. The death of my dad in 2018 fit into that narrative. The book starts with the long poem for him, Green Side Up. That was the way my dad lived his life, always optimistic, always seeing the good side of things. In a lot of ways, his death made me have to think about what that meant to me, being optimistic in a world I wasn’t always sure I understood.

In Hechizo, there was more yin than yang. In that book, I respond a lot to the awful of the first Trump presidency, tempered too with the pendulum swing from the excitement of the move to Mexico to the realization that as good as life was seeming, there was a need to return to looking harder once again at the world—in particular the rise of authoritarianism, ongoing environmental devastation, all that. I needed as well to take a harder look at my own personal demons, in particular my alcoholism, which because of the move I needed to see again in a clear light. The hechizo, which is a spell that can be for the light or the dark in any of us, was cast by many very different forces. Overall? It was by Mexico itself.

So Volverse/Volver tries to reconcile all those different forces. There’s a sense of what in Hebrew we call teshuvah, which is a return of the self to its origins, and in that idea, a going forward. It deals with recognition and amends, with hope, forgiveness, balance, beauty.

A key element in Volverse/Volver is the notion of grief anew—my mom died in 2022, which was extremely hard and yet less difficult than the death of my dad because I had just gone through that grief for my dad and I had a better sense of how to understand it. The years between the deaths of my mom and dad gave me and my mom a chance to talk more, to become even closer, and I saw her own sense of what her death would mean for her. It was her own becoming and return, her deep belief that her death would mean being with my dad again.

Does it matter if I thought it true? That they are together? I hold the metaphor of their after-this-life togetherness, their love, very closely.

The section dealing with grief, which is called Dolores/Dolor—my mom’s name is Dolores and dolor in Spanish means pain—also gave me the chance to write about David Shapiro, one of the great poets of our time, who had been my teacher and more importantly my friend. I also dealt with the death of my friend John Polce, who had been extremely important—he still is—in my sobriety.

The book also faces my growing identity in Mexico as a person of the two places. I became a Mexican citizen, which is a very big deal to me. In the opening notes to Volverse/Volver I wrote: Mexico is…a great nation and my love for Mexico, very different from my native country, is quite deep. The country fills me with a kind of wonder and awe and it has since my first visit here in 1986. William Burroughs wrote that something falls off you when you cross the border. Some weight, some burden. I read that before my first visit here but as soon as I arrived, I felt it. I felt somehow more myself, more alive. It felt like a return, as if there was something here for me that had been waiting. In Hechizo, I have a poem, my grandfather in Mexico, in which I talk about how much my grandfather loved being here: am I living his dream?

In a sense, Volverse/Volver gives me the chance to plant a different flag in the earth, not one of a single nation but one that stands for a commitment to love, social justice, and beauty. My good friend, the poet Joseph Lease, and I have spent a lot of time on the idea of soul-making, which goes to Keats and his idea of what this world is. My vision is for a poetry that allows me to engage with the world, the world engage with me, and somehow out of that comes something powerful and meaningful.

Leslie: In a nutshell, what have been the key changes in your personal circumstance since you left the USA that drive this collection?

Mark; Nutshell has been my ongoing recovery, which started long before in the US but I needed to understand again given all the changes in my life, my becoming a Mexican citizen, a greater engagement with poetry—writing, translating, reading—and a deeper engagement with the world in a physical, emotional, and spiritual sense.

Really major in my life is that shortly after we moved to Mexico, we started to create the space that we call Rancho Alegre Apolo, named after our chocolate Labrador Retriever, Apollo. It started as a small house with some land, known then and still as Casita Cannonball, for our black Labrador who moved down with us in 2016 but died six months or so later. We bought more land after a neighbor farmer sold his farm to a developer and we were able to recover a lot of that—it would have been environmentally awful for the community especially in terms of waste disposal and water use. Then, we bought a house that was next to the first house. It had a small outdoor sculptor studio. We turned that house into a studio for Katherine, with a reading room/writing space for me. The sculptor studio we expanded into an outdoor performance space for readings and concerts, and we set up a part of Katherine’s studio space as a space for exhibitions. So we now have a small cultural arts center, the Centro Cultural Liliana Loth, named for Katherine’s paternal grandmother, where we have a couple of events a year.

The rancho matters to me a lot. It’s close to Oaxaca city but is very rural. Our neighbors are all farmers and shepherds—what makes it a rancho is that the neighbors use the land we bought from the developer to graze their sheep, goats, and oxen. Their turkeys, roosters, and hens also seem to enjoy the views…

It’s absolutely beautiful there. I don’t think I’ve ever felt quite as happy and peaceful as I do when out there, reading, writing, going for long walks with the dogs. This is the place where I get almost all my work done. Truth is, when I’m in centro Oaxaca, I’m way too happy to socialize, meet up with friends, all that. So I like the solitude the rancho gives me. Our colonia is very small, I can socialize that way, but it’s very easy to go about the day and see no one, save Katherine.

Less fun circumstance? In early December 2023, Katherine fell and suffered a severe concussion. She still suffers from the effects of it. Only recently has she been able to paint or write. Just awful. I’ve been invited to Cuernavaca to read at the big poetry festival in November and we’re hoping that she’ll be able to make it. It will be her first time traveling since the concussion. A nightmare.

Leslie: How would you describe the developing ‘third voice’ of these poems? In writing them, how did you experience the grieving process? What helped you to come to terms with both world politics and your own ‘personal furies and lizards’?

Mark: Leslie, that voice that has emerged in some ways is hard for me to figure out because there it is—a kind of short lined unending flow of language, a wall of sound as it were—and while I work really hard on it, it isn’t always clear to me how it developed so quickly after moving here.

I know that before, in my last few books of poems written in the US, especially That Train Again (Lavender Ink, 2015), I had started thinking a lot about the ways to accelerate the line, to give it another kind of emotional and physical force. I was interested in how William Carlos Williams did that so well. It has to do with breath and movement. I think a breakthrough for me became the realization that I didn’t have to worry about the line stopping at the end of the line, that it could move to the next line and that with rhythm and breath I could make something happen that way.

One challenge was to do it with as little punctuation as possible. I didn’t want those marks littering the page.

What I didn’t expect to happen? That as I became more confident with that way of writing my voice would become more confident about saying things I thought would reflect both experience and meaning. In earlier books and poems, I was pretty content to write about what was going on and let the reader go where the reader wanted to go. Then I started to realize that there was more I wanted the poem to do than be a reflection of my experience. I wanted the poem to become a greater experience itself.

Is it always working? I don’t know. I’m still working on it. What it does allow me to do though is say things that I think matter. Maybe it’s a function of age. I think I have some wisdom. And I’m no longer teaching! There’s stuff I want to say. And sobriety maybe. I’m interested in being as present as possible.

Next week, in Part 2, Mark Statman talks about his Latin American poetic influences, Mexico and Volverse/Volver.

ABOUT LESLIE TATE’S BOOKS:

I interviewed artist Sarah Ross-Thompson whose exceptional Collagraphed prints use fabrics, lichen, porridge and string to create images of the dramatic Scottish Highlands where she

Part 2 of my interview with Mark Statman looks closely at Mark’s Latin American poetic influences, his life in Mexico and ends with an extract

I interviewed international poet and translator Mark Statman about Volverse/Volver, his 14th published collection. Mark, who has won national arts awards, is Emeritus Professor of Literary

I interviewed Lisa Dart, finalist in the Grolier, Aesthetica and Troubadour Poetry Prizes and author of The Linguistics of Light (poems, Salt, 2008), Fathom (prose

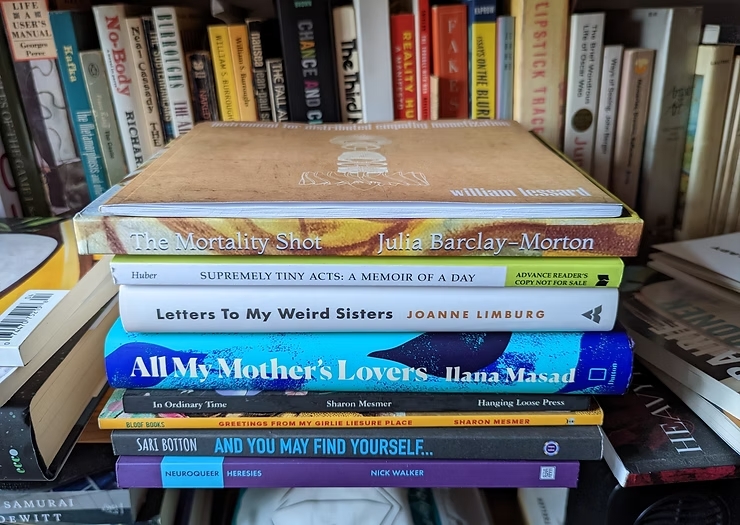

I interviewed writer Julia Lee Barclay-Morton about her experience of autism. Julia began as an experimental dramatist in New York, moving to the UK to

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |