SARAH ROSS-THOMPSON AND THE ART OF COLLAGRAPHED PRINTS

I interviewed artist Sarah Ross-Thompson whose exceptional Collagraphed prints use fabrics, lichen, porridge and string to create images of the dramatic Scottish Highlands where she

Part 2 of my interview with Mark Statman looks closely at Mark’s Latin American poetic influences, his life in Mexico and ends with an extract from Volverse/Volver, his most recent published collection.

Mark, who has won national arts awards, is Emeritus Professor of Literary Studies at Eugene Lang College of Liberal Arts, The New School, NY, and now lives in San Pedro Ixtlahuaca and Oaxaca de Juárez, Mexico.

Leslie: You have a long-term relationship with Spanish-American poetry, history and culture. Who have you been influenced by, and what are the key elements of your personal ‘in betweenness’ that have gone into the writing of Volverse/Volver?

Mark: It’s hard for me to say, at this point in my life—I’m 67 years old, which is sometimes hard for me to understand or imagine, since I do feel I’m still just starting out, still in the middle of everything—who influences me right now. I think it has more to do with what I’m interested in. It isn’t that I can’t be influenced, it’s just that influence feels a little beside the point.

As a younger poet I think I was always looking to be influenced. It was a form of learning. What I was saying about Williams before, for example. Although in this case it was seeing him doing something and wondering what I could do with that. I could name a lot of poets over the years who helped form me. It starts with Whitman, of course. Dickinson. Where American poetry starts.

You’re right in seeing that poets who write in Spanish mean something to me. That seems to have been largely situational. And personal. My dad’s family on my grandmother’s side is from Cuba. Some of them were for Fidel, some against, but everyone eventually left the island. My great-grandparents are buried in Havana. Lorca had a profound effect on me because of translating him. In a lot of ways, translating Poet in New York (Grove, 2008), with Pablo Medina, was a real turning point for me in understanding how much larger poetry was than I understood before. And in a more intimate way, getting under his skin—that’s how Pablo would talk about it—meant he also got under mine.

As I said, though, these days it’s more interest than influence. The Mexican poets. As part of becoming Mexican I’ve felt a happy need to learn more about them. So I’ve been reading Mexican poetry very deeply. Some are obvious, some less so. Some write in Spanish, others who write in what here are called lenguas originarias, of which there are over 60. A Mexican poet who continues to move me is Gloria Gervitz, whose Migraciones is one of the finest books of poetry of the late 20th/early 21st century in any language. Myriam Moscona, who writes both in Spanish and ladino, has been on my reading list. So are Maria Baranda, Araceli Mancilla, Efraín Velasco. I should note that the latter three are folks whose work I’ve translated or been translating—so it makes sense my active interest in them.

The substack I started early this year, Poet in Mexico, has been really important. It’s been a way for me to get somewhat out of the META/MAGA Facebook/Twitter/X world and still write about what’s going on with my poetry and politics thinking. I’m also on BlueSky.

Each week with Poet in Mexico, I try and feature a poet whose work has meant something to me. They’ve included poets who are contemporaries of mine. They’ve also included poets who were just ahead of me and who kind of helped me along. And they’ve been younger poets. Or poets whose work I’ve recently gotten to know better and better.

Someone wrote me and commented that a lot of the poets I’m publishing are some pretty heavy hitters in the poetry world. They’ve wondered about how I’ve been able to do that. I have to admit that I don’t quite think that way. It’s more along the lines that these folks are my friends. You get to spend 50 years or so in the poetry world, you meet a few people.

They are folks who mean a lot. It’s really wonderful to be able to do this. Your readers can find it at https://open.substack.com/pub/markstatman.

As for the in-between—I’m not sure I feel so in-between anymore, at least not in the way I did when we first moved here, and not in the spirit that moves Exile Home and Hechizo. I think one of the things that the reconciliation of Volverse/Volver marks is that I’m pretty comfortable with where I am right now in my life. It doesn’t mean I’m not constantly reaching and exploring. Just that I’m more active in the present. I remember talking with my psychiatrist during those times of Covid when I was getting tired of waiting for this all to be over. I came to the realization that waiting for that was a kind of fool’s strategy. No one knew what was going on so the idea needed to be to live in the moment. That thing that was kind of a cliche of the 60’s—Be here now—started to resonate with me in an unexpected way.

The divisions in myself that I felt a lot—the in-between—seems less a problem for me now. Here’s something I wrote in a recent Poet in Mexico; I’m reflecting on what the month of September in Mexico—el mes de la patria—the month of independence from Spain, this year marks the 215th anniversary of that—means to me. The ideas can go much bigger than this moment, though.

Here, in southern Mexico, and throughout the country—though I admit this is less true in the more northern, industrial, desert parts—I feel this engagement, I feel this closeness, I feel this song and this flight. I feel life.

It isn’t just the histories of Mexico which fascinate me. It isn’t just the poetry, music, art, food, all those things of my everyday life. It isn’t just the sheer physical beauty of the country. It isn’t just the people.

It is all those things together. And it’s more. A resonance beyond language. Here I am, a güero, light-skinned, light hair, blue eyes. A New York Jew. I’m obviously different. Except, most times, when it comes to it, no one makes me feel different. I’m a mexicano gringo. I feel a funny stirring, despite its violence, when I hear the Himno Nacional. Listening to the presidential press conferences every morning, I feel a kind of pride in nuestra presidenta. September, this our mes de la patria, I fly a Mexican flag on the car.

I like the dynamic changes going on here, culturally, politically, socially. Mexico is a country whose democracy is very messy. In many ways its still very embryonic. US media reports talk about cartels and borders. Living here, being here, there’s something else going on. I feel it happening. And it amazes me. Makes me feel proud I can participate in this growth. Growth of a country. Growth of myself.

Becoming a citizen was a logical part of the evolution. Physical presence. Emotional connection. Spiritual clarity. I wake up each morning and go through the days with a sense of purpose. And fulfillment. I live in Mexico. I’m Mexican. I belong in it and it in me. I’m home. Like Brooklyn. Just much further south.

Leslie: Although Volverse/Volver is a single, unified text, can you select a short, representative section and explain how it fits into the whole, please?

Mark: I’m thinking: you and I have done a few interviews over the years and this has got to be the hardest question you’ve ever asked me! At first I thought maybe the poems directly about grief but I kind of talked about that before. So maybe just the poems that end the book? In a certain way, they answer your question about my in-betweenness. I think they also give a sense of the ways in which I’m ready for whatever excitement, whatever grief and joy, life nexts wants to dish out. So, the final poems seem a good way to end an interview?

stranger

exiled language exiled

spirits who listen

to far off voices questions

what why sea

green the world happens

we write in notebooks

on amate on papyrus

sweat clay sperm

letters and pictures of

unknown flora fauna

weaknesses for the

strange weakness for

conquest arriving

and burning boats

sacrificed and fire

animals children

say no and no and no

all in flames

in waves and terror

meditation beads the

gods and heroes

seeded teeth in the

earth paper and

breath and dreams

of return heavy clouds

first thunder then

lightning it’s bloodless

disappear and

our ever weakening

arms hands legs

spiral high we

keep moving

destiny and chains

we never get it

right ongoing music

orchestra divided

by the which of our

regretting and the how

smaller shadows

morning path

revolution of tigers

casting revolutions of

flowers revolutionary

days brimstone calls

to order to soldiers

who go off to other

sides of the world

home provides

beer arsenic

how to love

God if I don’t

love you the

calling cards of

change our actions

speak louder

than words thresh

cantar desert olvidar

they trumpet naked

before the gods

chocolate and calla

lilies we kiss naked

before the night

Pacific and poppies

what to tell the

lives coming home

what to say about

undone and grace

it’s okay to stop

okay to go

these paths we

make forever

strewn with

spices roses

calling cicadas

scattered orchids

a wild sun

without wings

Si hubiera Dios no

existirían los humanos..

—José Emilio Pacheco

world made we

made the world

God world the

wastrel world

vaudeville vagabond

wasted cried for

out cried against

to with what’s it

like to be human

apostles of peace and

war apostle epistles

no missive

to the world like

jacaranda lilac

lily of the canyon

this world deals in

princes of peace aces

of spades why do

we all have

to be in this together

cast one vote

for one king two votes

for the lady in

black the lady in white

the sacred brawls between

the bandit children and

the children of bandits

I haven’t stolen

anything today (yet) I

haven’t had a

drink watched a

movie blamed anyone

in the news for

anything (yet)

we fall to infernos

we have no wings the

waves and wind

swallow and snake

us to our homes

we fail ourselves

amaze each other

our countless worlds

upside down I

hear sirens call a

rooster accordion

I can hear the

temporary violin slither

dream footsteps

of furies and cheats

the bastards come

embroidered in flight

I’m out the

door and on the

road a bandit prayer

hemlock and bread

you’ll get nothing from

me I’ve given all

I’m headed south

come with come

along come gone

ABOUT LESLIE TATE’S BOOKS:

I interviewed artist Sarah Ross-Thompson whose exceptional Collagraphed prints use fabrics, lichen, porridge and string to create images of the dramatic Scottish Highlands where she

Part 2 of my interview with Mark Statman looks closely at Mark’s Latin American poetic influences, his life in Mexico and ends with an extract

I interviewed international poet and translator Mark Statman about Volverse/Volver, his 14th published collection. Mark, who has won national arts awards, is Emeritus Professor of Literary

I interviewed Lisa Dart, finalist in the Grolier, Aesthetica and Troubadour Poetry Prizes and author of The Linguistics of Light (poems, Salt, 2008), Fathom (prose

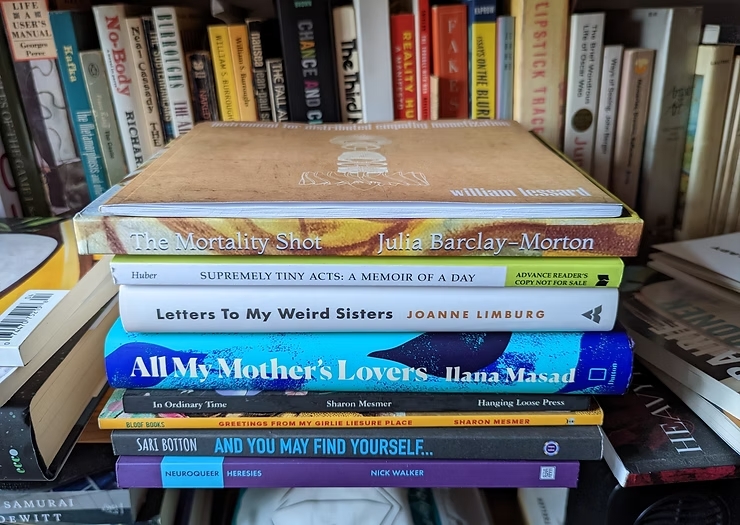

I interviewed writer Julia Lee Barclay-Morton about her experience of autism. Julia began as an experimental dramatist in New York, moving to the UK to

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

2 responses

Thank you for this interesting interview and introducing me to modern poets of Mexico. much appreciated. warmest wishes Barbara Bloomfield

🙂 🙂 🙂