In part two of their interview neurospicy crime writer Suzy A Kelly talks about their physical conditions, gender ambivalence and creative processes. Suzy’s writing has been commissioned by the National Library of Scotland and her short stories have been published in New Writing Scotland, Northwords Now, Gutter Magazine, and by the British Fantasy Society.

Leslie: How do you manage your physical conditions and remain creatively active?

Suzy: I’ve been diagnosed with ME/CFS for over 20 years. It causes debilitating pain every day. It leaves me so exhausted that I often need help to walk, dress, cook or otherwise perform simple human activities. It makes every step feel like I’m walking on burning, needle-filled quicksand. My mood, concentration, and memory are also affected. Terry Pratchett referred to Alzheimer’s as ‘an embuggerance’ and I think of ME/CFS the same way, except people don’t tell Alzheimer patients that their disease is purely in their imagination.

This means that my writing days must be carefully planned. Christine Miserandino created the Spoon Theory in 2003. In short, chronic illness patients wake up every day with a set amount of spoons which they can use for daily tasks and pleasures. If my energy levels are the equivalent to five spoons, then I’m forced to choose what I’m willing to spend those five spoons on. The accounting is specific. There’s no wiggle room. Say brushing my teeth and shoogling into clothes demands 3 spoons, and brushing my hair demands another spoon, this only leaves me with 1 spoon to work with for the rest of the day. So I can either cook something to eat and have no spoons left for writing, or I can order my lunch in and use that 1 available spoon for writing. But without extra caring support, I couldn’t even do that. For me to sustain a creative practice, it means my favourite person has to take over the housework without help from me. All while sustaining their own creative practice. It’s taken decades for me to learn how to work with these physical and mental needs without feeling guilty or like an utter failure.

Then, at the age of 46, I was diagnosed with ADHD which comes with its own extra bag of tricks. It’s more than just the ability to make glaringly obvious mistakes or indulging in impulsive behaviours, or being unable to stop talking or interrupting people. It also brings executive dysfunction, rejection sensitivity, emotional dysregulation, and burnout. These things can leave writers paralysed with inertia and fear, unable to put words on the screen for weeks or months at a time.

Before I knew what it was, or why I thought in the ways I did, I beat myself up for it. I called myself terrible names. I starved myself or overate. In my younger days, my dopamine deficiency caused me to punish myself with sex, drugs, and too loud rock and roll. It left me feeling like I’d failed at being human and that I deserved to die, which culminated in a botched attempt to stop living.

After a tour of stimulant medications, and a brief sojourn into the land of serotonin syndrome, my ADHD is finally controlled. This means I can read and research for longer bursts. Although the ME/CFS means I still run out of spoons, I have more clarity in my thinking, which means my editing skills have improved. My word count is never over 500 words per session and it doesn’t need to be. I’m not in competition with anyone. Writing is my lifeline. It’s the only way for me to build a life for myself outside my sickbed. Robert Louis Stevenson inspires me in this regard. I think of him as a poorly wee boy, staring out his window on Heriot Row and imagining life beyond, and it encourages me to keep going. The trick is to embrace the present writing moment and to enjoy every word you can muster onto the page, even if you’re writing a murder-ridden historical crime novel, like I am right now.

Leslie: How has gender affected your life and your writing?

Suzy: I was born in the mid-1970s, the time of the pat-the-bit-of-crumpet-on-the-bottom type of sitcoms. Ladies-in-lingerie were also considered a vehicle for comedy chases. Meanwhile, the hands that did dishes were expected to belong to a specific type of human and these humans were expected to have very soft faces too. It was all very confusing. I didn’t have the words to express who I was growing up. It bewildered me that men at that time expected different behaviours from me and my sister than from my brother or male cousins. ‘Why are we expected to do the washing up while the others sit around drinking beer or playing Nintendo, Mum?’

When I was a bit older, I didn’t understand why it was considered odd to dig around in the dirt, feel uncomfortable in a dress, and to not want babies. I was a ‘tomboy’, apparently. A failure at presenting myself to the world in the accepted girlish way. Rather than being a still, silent child, I chattered nineteen to the dozen about every subject that fascinated me. I cartwheeled along neighbours’ walls. I wanted to be Officer Poncherello from CHiPs careering down the highway on a motorbike, chasing bad guys. If I kept up the gymnastics, I was sure I could be a stuntman like The Fall Guy. I didn’t want to be Amy flirting with the Faceman. I wanted to be riding in the van as an integral, fighting member of the A-Team. This meant the girl gangs weren’t keen on having me and neither were the boys. I couldn’t understand why being one or the other mattered so much. I never felt much like either. I mean, I had the parts that were assigned to me, but why did it then follow that I should act in a certain way, think a certain way, dress a certain way, or be referred to in a certain way because of my genitals or ability to reproduce in the future? I understood that the gender I was assigned had been prevented from having things like voting rights and that there were political movements that sought to prevent women from maintaining full control of their bodies. I knew all of that historical injustice was wrong and that it was only right for everyone, regardless of their gender, to bandy together to fight such misogyny wherever it was found.

I still feel the same way forty years later. Yes, sex chromosomes affect particular biological functions. Yes, neurodevelopmental conditions like ADHD affect those assigned female at birth differently. But I’m not female. Neither am I male. I have no need for a particular gender. It’s a privileged position, I know. But I am, first and foremost, a Suzy and I do not care who is using the bathroom next to me. As long as they’re safe and their privacy is respected.

But I was forced to flip between binary gender performances growing up. You needed to in order to survive the council estate marbles-in-socks, lets-have-a-rammy-on-the-beach era of the 70s and 80s. You had to be physically able to fight while remaining soft and able to charm your way out of danger. You had to be able to tell the filthiest of jokes with the sharpest of wits while knowing how to plait the tail of your My Little Pony.

School bullies and internet bullies have no patience for such ambivalence towards gender these days. The discourses are fever pitched and usually cruel in their attempt to pathologise those who don’t conform to narrow expectations of gender. I’m in the privileged position of not hating my physical self because of its particular sex parts. I mostly despised it because of its size. It was too small and then it was too big. It was too scarred. It was too lined. In short, it was too imperfect.

To my mind, the imposition of fixed genders caused, and causes, irreparable harm. Some humans are the gender they were assigned at birth. Some are not. So what? We know who we are. You just need to show us love and respect. I’m lucky to be married to a gender fluid person. Sometimes he inhabits the world with a more masculine energy, sometimes she has a more feminine energy. They are my favourite person. Sometimes they wear combat trousers. Sometimes a dress. Accepting people as they are is the kindest, most harmonious way of inhabiting the universe. There is no justification for hate and, at the end of the day, it’s no-one else’s business what you keep or don’t keep in your underpants.

This also feeds into my creative work as I’m comfortable writing from any gender position and none. I think it leads to a stronger, more empathic, understanding of character.

Leslie: What have been the most helpful and least helpful things you’ve learned from your creative writing courses/academic studies?

Suzy: I would begin with the caveat that writers do not need academic qualifications in order to have their work published. Some of the best contemporary writers have extensive backlists and have no need for an MLitt.

My own studies began with the Open University and it took eleven years and two changes of university before I got my degree. I then went straight from graduation to the MLitt in creative writing at the University of Glasgow. Two years after that, I wangled a place on their doctorate to write an historical crime novel and an accompanying thesis. I’ve also attended countless online writing courses, local writing group courses, and several week-long stints at Scotland’s creative writing centre at Moniack Mhor. So you can say I’ve experienced all levels of creative writing courses and I’ve still got lots more to learn.

What creative writing courses are best at providing is community. You need to surround yourself with like-minded souls who understand the emotional demands of releasing creative work into an uncaring publishing world. They will commiserate with your every rejection and they will cheer on your every success. When this is formalised in a university setting, you also learn to give and receive critical feedback with these same creative cheerleaders. It teaches you to become less precious about your work. You also learn to slaughter your darlings pretty quickly without taking offence. It helps you to build a creative practice that specifically works for you. Do you need to sit for six hours and complete two thousand words before you consider it a good writing day? Good, you do that. Do you need to sit and fret for several hours before writing five hundred good words? Then do that without apology.

Writing within a university department gave me the confidence to create my own writing rituals. It helped me develop my own thinking around literary theory, about other writers, and about the world in general. It exposed me to works that I might not have thought of reading on my own. Sure, I hated some of them, but I learned to understand why. You learn which techniques work for you and those that do not. I never thought I’d enjoy the lyric essay but now I’m writing a thesis that cannibalises lyric essay elements.

Formal study in creative writing also provides great practice in meeting deadlines and creating a professional writing self. As a neurodivergent writer with chronic illness, my ability to meet deadlines varies. It’s not something I always have control over. But I’m open about my struggles and I’m happy to explain this to whoever’s setting the deadlines. Sometimes people are patient. Others are not. But perhaps if enough of us do this, then the publishing industry can work to become less ableist.

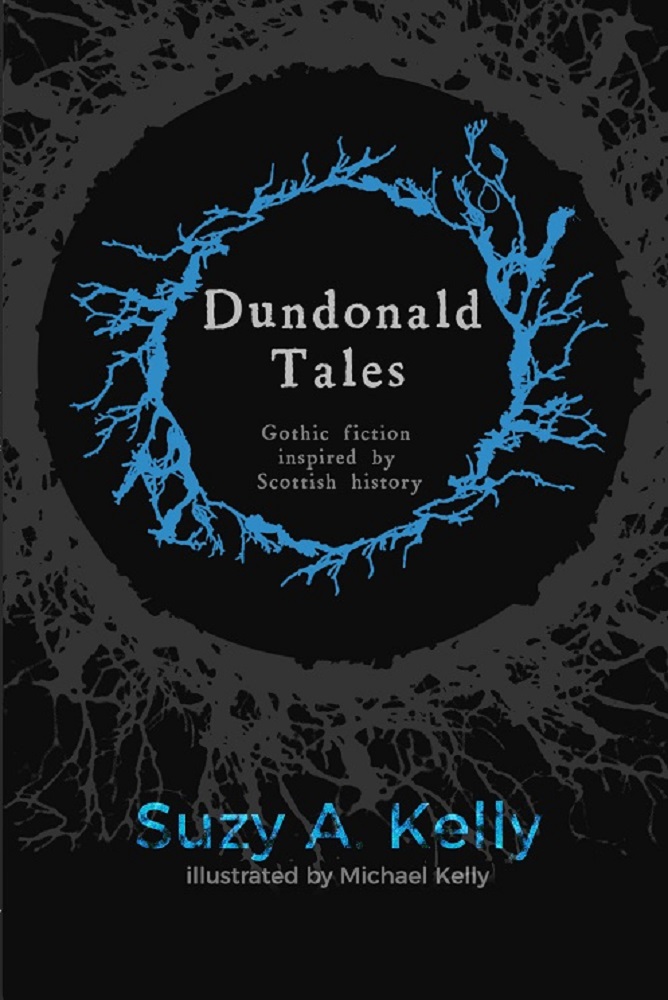

University study also gave me the opportunity to pursue projects that most excited me. As part of the MLitt, I worked on an illustrated book. ‘Dundonald Tales’ was a gothic historical fiction collection which I wrote and my favourite person illustrated. It was based on my village’s church session book from 1605 and it centred around its history of witchcraft trials. This project allowed me to experience the huge amount of work involved in self-publishing, but also to know the joy of creative freedom. It also meant I was able to have my first book launch in a medieval Royal Stuart castle and that will always tickle me. Creative writing courses taught me how to love the editing process, too. No, I’m not joking. Editing is my favourite part. It’s where you get to refine, restructure, add layers and subtext, and shape the heart of your story whether it’s a novel, a short story, or a piece of flash fiction. I love working with editors to make the work as good as it possibly can be. It’s a gift. Sometimes plots or character development falls flat. Sometimes the structure is weak. Other times you’ve phrased something really awkwardly and it ruins the reader’s understanding of your story. An editor will help you kick that baggy story into shape. It’s a joint endeavour, which all of my studies prepared me for.

One of the more unhelpful aspects of creative writing studies is the financial burden involved. Grants and stipends are precious few, which means it’s the reasonably well-off who get to attend and benefit from the most prestigious courses. However, places like Moniack Mhor do bursaries for writers like myself on low earnings. I would not have experienced their week-long, fully immersive courses without this help. And the hobbit house ceilidh night (go find out for yourself) is something a writer never forgets.

There is also a lot of snobbery involved with academic creative writing studies, especially from other disciplines. You soon learn to justify why you’re researching what you’re researching. I laugh when people show excitement at me studying a doctorate, and then their face falls in confusion when I say it’s in creative writing. ‘Oh, can you do a PhD in that?’ Yes, you can and I’ve been doing it successfully for the last three years.

The most helpful courses formed the bedrock of my creative writing. I chose undergraduate courses in other areas across the humanities, arts, and sciences. From learning to speak and write Gaelic, to the history and folklore of Scotland and beyond, to the Romantics, to developments in psychology and sociology, works of gothic literature, heritage and culture studies. I made it my business to read as widely as possible. It gave me the confidence to write whatever I want in whatever genre I choose. It also prepared me for the huge amounts of research required to write a Victorian crime novel that flits from industrial revolution Glasgow to Belle Epoque Paris, to Gilded Age New York. Nothing is ever wasted.