Part 2 MARK STATMAN: MEXICO AND THE POETRY OF GRIEF AND CELEBRATION

Part 2 of my interview with Mark Statman looks closely at Mark’s Latin American poetic influences, his life in Mexico and ends with an extract

When I interview musicians on my radio show, there’s a question I avoid. Partly because it’s a cliché, similar to, “Which comes first the words or the music?” but also because of where my question might lead.

Let me explain. The question I’m thinking of is, “Do musicians hide behind their instrument?” In itself it’s nothing, merely a standard riff. But it might take us into difficult territory – for instance, how it affects their music or (even) whether my guests are bad actors. So I keep it to myself, partly to play safe but also because when I’m in the studio I’m using the mic as cover myself. It makes me think of shy actors who hide behind their part.

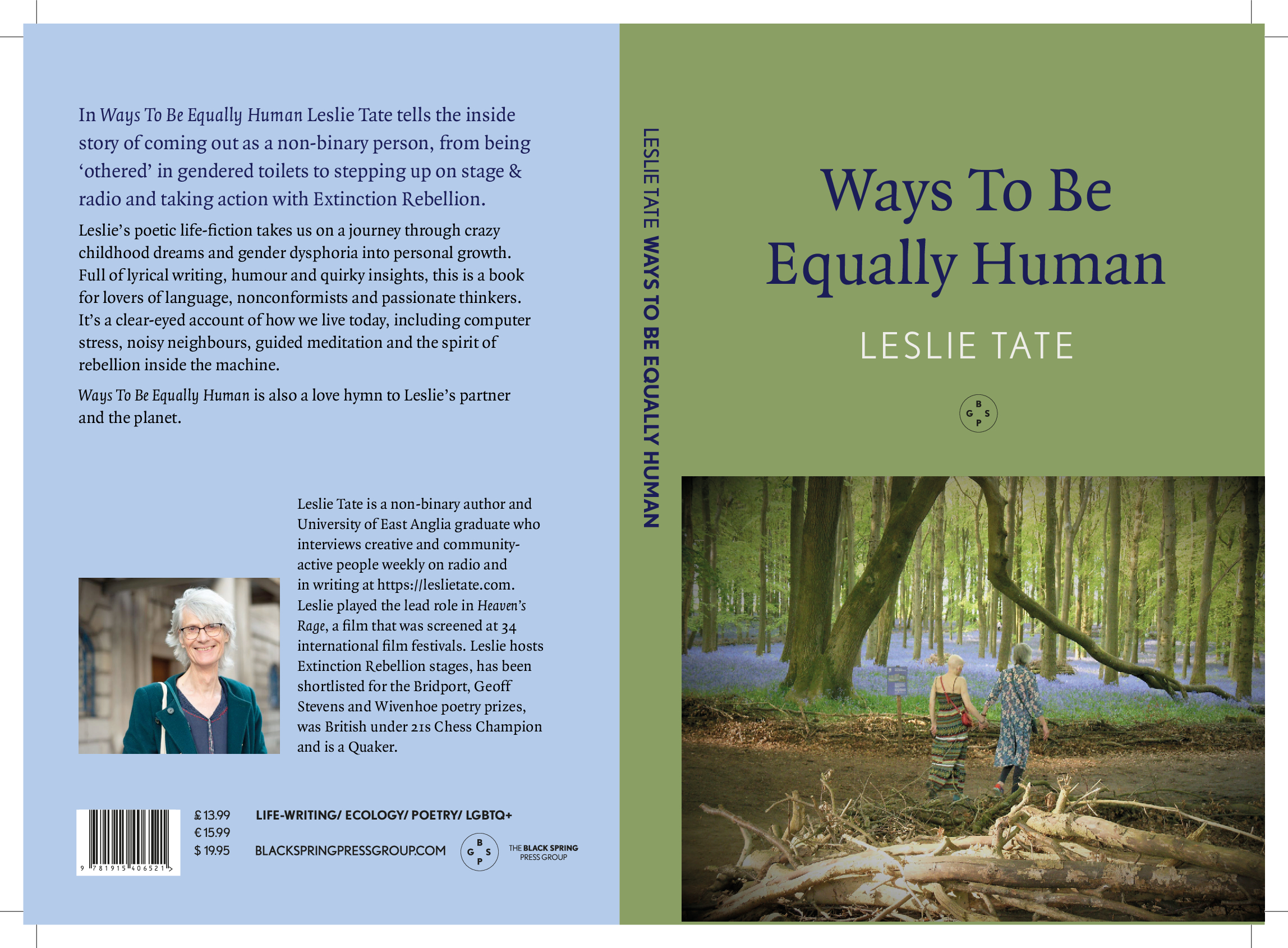

The same question comes up when I’m writing. The voice I’m projecting is something artificial I’ve worked on. I want it to sound natural, alive and present, but also weighty, filling up the page. In Ways To Be Equally Human, p. 95, I’ve described it as the voice that shifts between the spoken and written registers…

The slow way is to put it in writing. Word by word – crafted, examined, looked up in the dictionary and recast again and again. It’s a double deck of cards, shuffled and dealt out in a game of patience – one that never ends. And behind the writing there’s a guessing game, a back-and-forth shift, attempting to find a way. If it’s in writing, then it has to be perfect.

BUT when you speak, you’re in the hotseat. At the turn of a switch, it’s live and there you are! There’s presence and connection. The voice leads, pausing and repeating and putting in ‘you knows’ and ‘sort ofs’, and sometimes struggling for a word or a placename. Then, without warning, it all comes out in a rush.

Writing’s more accurate, of course – quotes and looking up facts, checking for meanings and weeding out redundancies – but what makes a book is the coming together of disciplined telling and random asides. It’s the oral-in-the-written, the trained voice on-air, the formal and the casual. All that, and the edit, brings the book to life. The trick is in the mix.

So however we tell a story, there’s a sleight of hand involved. And unlike academic essays, stories don’t list their sources. So when I write about the radio in Ways To Be Equally Human, I use first person, but stretch it to capture the physical reality of the studio. It’s calculated and it’s emotional. I’m trying to squeeze in enough detail to substantiate and universalise the story without losing the personal voice. And to keep it alive, I intersperse the narrative with occasional metaphors.

So here’s the complete story from Ways To Be Equally Human pp. 72 – 76.

I present an internet radio show where I interview local guests and play their musical choices. It’s a 24/7 station, going out from a studio in a rundown building next to flats at the top of a hill. To enter the studio, I type in codes on a keypad and switch off an alarm, then cross a large room to a doorway in the corner. The studio’s in there, sealed behind glass like a space capsule. Inside its white-walled box there are computers, monitors, control boards with lights and sliders, photos of presenters, and three oval-shaped mikes hung like lightbulbs from metal arms.

The studio door usually stands open, so sometimes the broadcast picks up ghostly noises from the next-door dance class, or chatter from the big room. It’s a sign of the radio station’s openness. It’s also the only way to stop the studio overheating.

Today, as usual, I arrive early. The big room feels like an entrance hall. It’s a meeting place for techies, creatives, chatterers and people on a mission. But this evening it’s quiet except for a trickle of sound issuing from the studio. I put down my bag then poke around with a USB behind a computer. I’m rehearsing the interview in my mind. Glancing at my watch, I go to the studio and check the main screen. Reading its blue and pink bars, I see there’s an overrun, but I’m nervous of correcting it. Is it OK to delete? Do I know what I’m doing? And if I bin some tracks, can I restore them? Finally I do delete, one track at a time. A voice inside me says it’s fine, but another voice is telling me I’ve blundered.

The doubt continues when I return to the big room to prepare my show. Sitting at the computer, I work my way through a succession of searches, playbacks, conversions, numbered carts and edits, using headphones occasionally to monitor my work. When I’ve finished, even though I’ve got half an hour to go, I’m unsettled. There’s a fear that one click too many or a wrong command might end up in silence.

I did silence my show once. I was trying out effects with sliders. It was the first time and I forgot about the voice mikes. The music faded and I launched into what I thought was a jolly-jolly announcement. Switching to my guest I continued chatting without realising no one could hear us.

But today my guest is a musician, and that’s comforting because J has recorded several albums, so he understands radio. I do know he’ll have to tune up and then hit the note, which makes his job harder than mine. With that comes a thought: maybe he’ll want sound that’s super-high quality? For a second I’m reminded of my weekly comedown after the show. But everything changes as he walks in.

J’s lean and chiselled, slightly bearded, young and rugged – a perfect indie rocker – and surprisingly diffident. But get past that and he’s deep, as I soon discover. Speaking sotto voce, he says hello and I show him to the studio, asking about his music. After tuning up and a mike check, we talk about the interview. There’s a gentleness about him and a hint of sadness. It’s as if he’s searching for a lost song. Maybe he’s been unlucky in love or he’s on a long journey, there’s a hidden story that makes him who he is.

Our on-air session goes quickly. We’re both performers, so we fill up every moment with words, songs, guitar riffs and stories. It’s unscripted and surprising. There’s a polished, high-energy power to J’s music – he’s a singer/guitarist with a big band – but when he stops playing he reverts to his private self.

“I have these moments… Minor key stuff. You might call them downs.”

My reply is a prompt. “Downs? You mean something like The Bends, Radiohead?”

J’s answer begins slowly, like a filler, then changes tempo. “The truth is, yes. Or sort of yes. It’s more like doubts, really. I’ve always had anxiety. It’s the thought that at any moment things might fall apart. And the doubt itself can bring on just the thing you don’t want. It’s about being alone – maybe thinking too much – counting all the losses.”

“So how does that work when you go on stage?”

“Oh, performing clears it. That’s when I get to let go. Every gig’s brilliant.”

“So, don’t think about it, just do it, eh? That’s a quote, by the way. Pink Fairies.”

“Yes, I get that…” Again, his voice slows, then switches up: “But I’d also like to say, that anxiety has its uses.”

“It does? Can you explain?”

“Well, all my songs are about it, one way or the other. It’s a drive. Because when I get worried, I sing about it. I think I’m filling a hole, heart on a sleeve, whatever. My music’s full of it.”

I nod and thank him. I say it’s good for the listeners to know. I find myself using words like where it comes from and making it happen as I ask him to play again. Not because we need to fill up time but because what he’s just said is one of those special, off-the-scale moments: a radio first. It stays with me as he tunes up and I joke about how musicians fuss. It accompanies his performance and my applause at the end, and remains in the background as I thank him and wrap up the show.

When we’re off air, I check that he’s happy with how it went.

“Happy,” he says.

“The stuff about anxiety – that’s OK?”

He nods. As I watch him pack up his guitar, I feel something flattening inside.

“Great show,” I say as I set the alarm and usher him out.

We part in a bare concrete space beneath a broken street lamp. Behind us the radio block is lit from inside. I know that light. It’s that special place where the voice in the air speaks and anything can happen. I know it from inside, like a child sheltering in a cave. It’s a world on its own full of dreams and special effects. Though in fact, what I can see is the glow of the alarm through holed curtains.

“Dark out here,” I say.

“But the show goes on,” he says, pointing to the block.

My last glimpse as I drive off is a man on a motorbike with a guitar strapped to his back. On the way home I listen to the radio. The song I hear is Joy Division, Transmission.

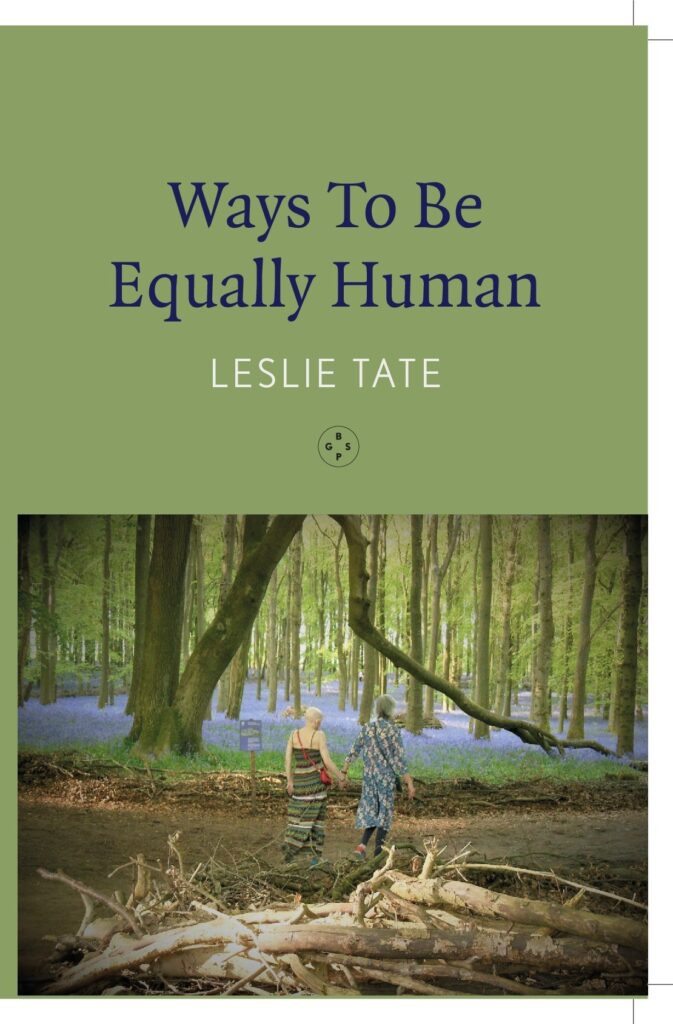

You can buy a signed copy of the book at WAYS TO BE EQUALLY HUMAN – Leslie Tate

You can catch LESLIE TATE IN CONVERSATION at Chapter Two Bookshop 10 High Street, HP5 1EP Chesham, United Kingdom on June 27th at 19.00. Event details: Ways To Be Equally Human: Leslie Tate In Conversation | Facebook

Next week: part three of the trilogy about writing & Ways To Be Equally Human

Part 2 of my interview with Mark Statman looks closely at Mark’s Latin American poetic influences, his life in Mexico and ends with an extract

I interviewed international poet and translator Mark Statman about Volverse/Volver, his 14th published collection. Mark, who has won national arts awards, is Emeritus Professor of Literary

I interviewed Lisa Dart, finalist in the Grolier, Aesthetica and Troubadour Poetry Prizes and author of The Linguistics of Light (poems, Salt, 2008), Fathom (prose

I interviewed writer Julia Lee Barclay-Morton about her experience of autism. Julia began as an experimental dramatist in New York, moving to the UK to

I interviewed Gillean McDougall from Glasgow, who edited the collaborative projects Honest Error (on Charles Rennie Mackintosh and his wife Margaret Macdonald) and Writing the

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

6 responses

Well done 👏 for the great work you’re doing .

🙂 🙂 🙂

Hi Leslie, thank you for this interesting article. I am always interested in how other creatives do things.

Thank you, Robbie!

Fascinating post. Thank you. I really related to the responses about anxieties – and how they disappear on performing.

Thanks, Jeff. Performing is a strange double-take experience! Now you see me, now you don’t.