Part 2 MARK STATMAN: MEXICO AND THE POETRY OF GRIEF AND CELEBRATION

Part 2 of my interview with Mark Statman looks closely at Mark’s Latin American poetic influences, his life in Mexico and ends with an extract

Authors don’t often talk about their failures. They might, in order to keep their audience guessing, channel their mistakes through a comic character or an unreliable narrator, but giving things away is a high-risk strategy and playing the fool invites disrespect. ‘Never apologise never explain’ is the standard trope and a whiff of ‘oversharing’ or ‘sentimentality’ can be enough to dismiss a book.

So for authors, keeping a deliberate distance avoids being ‘explained away’. Take, for example, Freud’s theory of creativity, which he saw as a release for forbidden wishes, driven by neurosis. Commenting on this speculation, Saul Bellow said, “You don’t build a skyscraper to hide a mouse.”

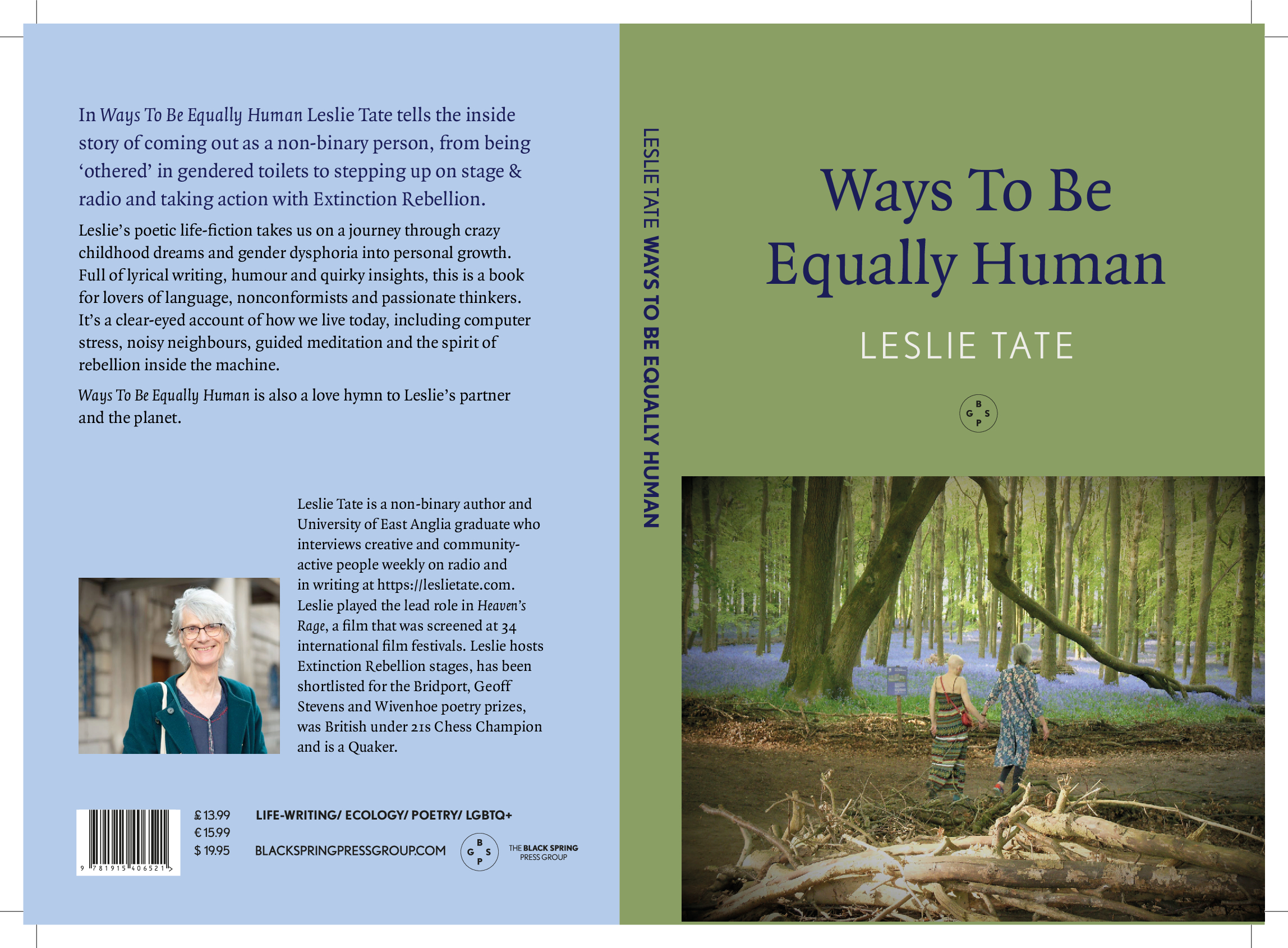

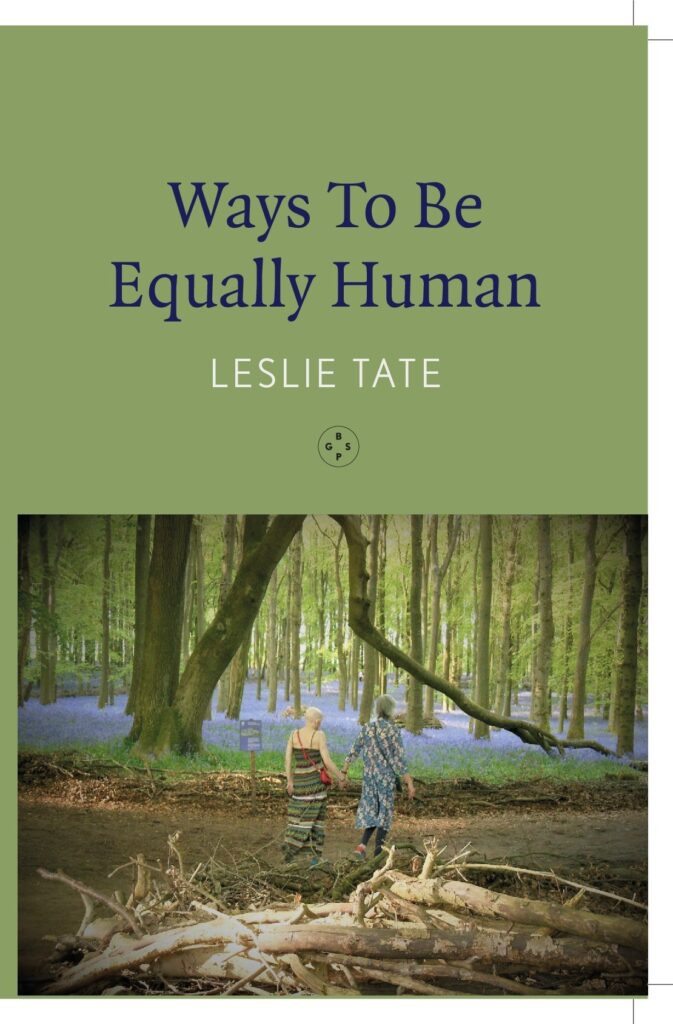

But today, other tactics are possible. For instance, when it came to writing about standup, I knew that some alternative comedians are willing to expose their own inadequacies. So I tried to capture their mindset in Ways To Be Equally Human, at the beginning of the comedy section pp. 86 – 87.

My name’s Tagalong. I’m not a bot and my friend’s a stand-up comedian. I’ve known him all my life. He’s small, slight, cheery-eyed, spotty all over (let’s say I’ve seen him in the shower) and young – although in fact he’s forty-ish, jobless and sponging off his mother. She calls him Toots, though his real name’s Trevor, which he says with a long E and a round-mouth O, laughing like a toff, then TREV when challenged by a heckler with who do you think you are? Trev the trucker and Trev the brickie, he says, for chewing in your mouth. But then he’s baby-face again, all apologies and talking about his fuck ups. He calls it his anti-comedy, where you don’t quite know if he’s acting the lad or really messing up. Sometimes I think he’s not quite sure himself. He’s like one of those old-fashioned clocks with figures on the hour popping out – the one that appears is usually a surprise.

“Comedy’s an attitude,” he says.

“Bad?” I ask.

He shakes his head.

“Then what?”

“It’s a way of being serious. Saying stuff.”

“You mean said the actress to the bishop – that kind of thing?”

“Pretty much. The naked truth.”

“But you set out to shock, yeah?”

“Yes indeedy. Throw in a few rocks. Keeps ‘em awake.”

“Which means it’s a wind-up?”

“Or if you’re thinking what I’m thinking.”

“So it’s really about pushing buttons?”

“Yup. And it can hide depression.”

I usually base these monologues on personal experience. For instance, I’m the alter ego behind this short story from Ways To Be Equally Human pp. 110 – 112:

Una Corda

It was his secret. Because it was absurd and couldn’t really happen it belonged to those voices he’d made up as a child, speaking of being chosen. There was always a chance, anything was possible; he’d believed that then. At four he’d his own private world, a place off-limits where everything was simple and the voices in his head told him he was a name – so why not at forty? Of course, as an adult he’d had to take a view, put himself out there as sensible and limited – D. Whittle, HR Manager, who people could depend on. Around the office he gave out advice, knew about procedure, told stories about panels who argued or didn’t know how to score, and only touched on something real when he chatted during breaks about after-school clubs and children learning music. Then he was warm and bright and quietly made up. And in that mood, he could go the whole day with pieces he was practising running through his head – usually scales or early Mozart. But mostly it was meetings and meetings, with agendas and progress reports and emailed spreadsheets and the need to be in charge, so that his passion only showed when he closed his door. That was when he smiled. And his smile grew, becoming fixed and dreamy, as he slid the bolt and returned to his desk. This was his place, his own secret studio where he held out his hands, just above the surface, leaning forward. And when his hands began moving, he was the keyboard whizz, practising his pieces for his debut appearance.

But inside he was cold.

At home he waited until the children were in bed then began his practice with the soft pedal down. He called it his hour, but continued many more while his wife watched TV. There was strain now in his playing, a tremor, as he imagined her watching. She was in the audience, shaking her head and refusing to clap. More likely, of course, she wasn’t much interested. So when he heard her on the stairs he carried on playing – quietly determined, expecting nothing. And when he finally joined her, Hazel was asleep and turned to the wall.

Next day she was curt.

“It’s Friday, Daniel,” she said while the children dressed.

He knew. This was her pass-out evening – a kind of payback, really, for what she put up with.

“Don’t worry,” he replied.

“I’m not,” Hazel shot back, as if in surprise.

“Not?”

“I don’t.”

“You don’t?”

“Won’t.”

“Won’t what?”

“Worry.”

Sometimes, he thought, they talked across each other like rival announcers.

“Seven o’clock,” she added, and busied herself with the children.

During the day while Dan went to the office, Hazel worked from home. It suited her. There was no fixed timetable so she could input graphics and add to products while looking up TV times and messaging friends. She even sent an email to Dan checking how he was. And when he came home, she asked about his day then mentioned Denise and Sam, who’d both had issues at school – small stuff, of course, but something to watch for.

That evening, when she’d gone, Dan talked and played with the children and read a bedtime story before taking them upstairs. “Now clean your teeth and snuggle down,” he called. “And sleep tight.”

Afterwards, as he crept downstairs, he was in the clear. The children were asleep, Hazel was out, and in a moment he’d be playing. Sliding the door shut, he sat down at the keyboard. The room was quiet. Taking a breath, he adjusted his cuffs. This was his chance.

Suddenly, he was alone. He’d nothing to give, and as for the music – he’d never really played it. There was a gap between him and the piano. The keys – what were they? – black and white and silent. And if there’d ever been an audience, they’d all walked out. He was D. Whittle, HR Manager, who moved his hands and made up what he did.

It was his secret.

As you probably guessed, Dan’s secret was mine as well, but I added the imaginary audience and how I felt as a teenage cross-dresser. I also drew on my time as a college middle-manager when fatigue and overwork made writing impossible.

So, contrary to the advice given at the start of this piece, I’m happy to speak openly about my failures. In this case Dan’s story comes out of my own desire, as a late-life author, to be ‘discovered’ after I die and awarded posthumous recognition (LOL).

Or to put it another way: in adapting experience to a book, we change who we are.

If the main myth of our times is the rise and fall of the wunderkind, then we’re all individualists on mission impossible. For me, to record that journey may be risky and the mindset complex but what counts is the person we become – and the qualities it brings to a book. (Ways To Be Equally Human p. 72).

If you enjoyed my blogs about writing my latest book, you can buy a signed copy of Ways To Be Equally Human here.

You can also catch LESLIE TATE IN CONVERSATION at Chapter Two Bookshop 10 High Street, HP5 1EP Chesham, United Kingdom on June 27th at 19.00. Event details: Ways To Be Equally Human: Leslie Tate In Conversation | Facebook

Next week, I interview Cumbria Wildlife Trust Writer in Residence Susan Cartwright-Smith

Part 2 of my interview with Mark Statman looks closely at Mark’s Latin American poetic influences, his life in Mexico and ends with an extract

I interviewed international poet and translator Mark Statman about Volverse/Volver, his 14th published collection. Mark, who has won national arts awards, is Emeritus Professor of Literary

I interviewed Lisa Dart, finalist in the Grolier, Aesthetica and Troubadour Poetry Prizes and author of The Linguistics of Light (poems, Salt, 2008), Fathom (prose

I interviewed writer Julia Lee Barclay-Morton about her experience of autism. Julia began as an experimental dramatist in New York, moving to the UK to

I interviewed Gillean McDougall from Glasgow, who edited the collaborative projects Honest Error (on Charles Rennie Mackintosh and his wife Margaret Macdonald) and Writing the

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |