Part 2 MARK STATMAN: MEXICO AND THE POETRY OF GRIEF AND CELEBRATION

Part 2 of my interview with Mark Statman looks closely at Mark’s Latin American poetic influences, his life in Mexico and ends with an extract

Prize-winning poet, Harriet Levin Millan writes about what she has learned from listening to the stories of refugees, and how she has turned that experience into literature.

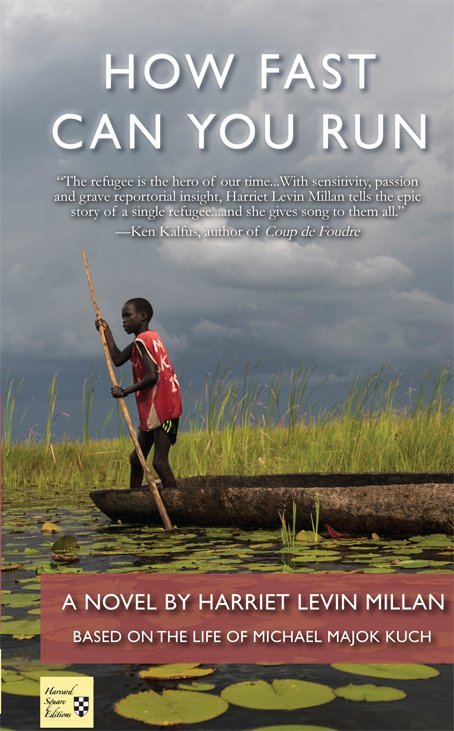

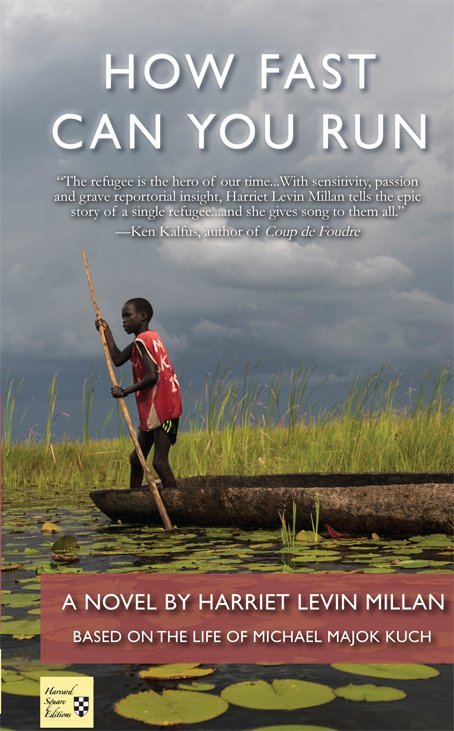

How Fast Can You Run, Harriet’s debut novel, based on the experiences of Michael Majok Kuch from South Sudan, has been selected as a Charter for Compassion Global Read and as a Forward Indies Best Book of the Year finalist in three categories. Harriet is also the author of two books of poetry, with a third to appear in 2018. Among her prizes are the Barnard New Women Poets Prize and the Poetry Society of America’s Alice Fay di Castagnola Award. She holds an MFA from the University of Iowa and directs the Certificate Program in Writing and Publishing at Drexel University.

Harriet writes:

Ten years ago I received a phone call that literally changed my life. It was extraordinary. Gerri Trooskin from our city-wide book club, One Book, One Philadelphia, called me with a most unusual request. She asked me to choose ten of my undergraduate creative writing students to interview ten Sudanese refugees and that these interviews would be serialized in Philadelphia’s City Paper. I remember thinking at the time that the word refugee was unnecessarily harsh. Why was she calling them refugees? I knew a lot of immigrants. I grew up in a pretty much completely Jewish neighborhood and a lot of my neighbors and friends were the children or grandchildren of Jewish people who had immigrated here from Russia or Eastern Europe either around the beginning of the 20th century or after the Holocaust. But no one referred to those people as refugees. It would have been considered impolite.

I teach writing and literature at Drexel University. Many of the students in my classes are from other countries, some of them are international exchange students, but others did come here under perilous circumstances. And even though I learned their stories in the essays they wrote, because in my classes my students are always required to write about themselves, I would have never called them refugees and they certainly would not have referred to themselves as refugees. They didn’t even like to be called immigrants. And I know this because I wanted to teach a class called “Your Immigration Story” and very few students signed up, but when I changed the name to “Your Global Story,” it was swamped. So even though I was surrounded by refugees both as a child and now as an English professor, I was really unaware of the movements taking place in the world around me until I met those ten Sudanese refugees and heard their stories.

After I picked the students who would participate in the interviews, I decided that we would hold them all together just in case anyone of them needed help. After all, these were American kids who had grown up in Philadelphia and they were going to be talking to adults who had just escaped from a war. We met in the local Starbucks because it had a second floor and there was plenty of room to space people apart. Some of the refugees we interviewed had arrived in Philly only in the past week, some from Darfur, and they were still traumatized from having seen people getting killed in front of their eyes and in fact narrowly escaping their own deaths. I did a lot of hugging that day as the refugees grabbed for my shirtsleeves as I ran up and down the staircase getting to all the different groups. I don’t want to say that my students were at a loss. They were wonderful, but it was good I was there that day to help out and comfort people.

“Compassion pulls you into the present,” says Karen Armstrong, the founder of Charter for Compassion a worldwide movement calling on the world’s religions to support a compassionate stance toward the world. Recently I read an article that a journalist wrote in which she said that learning about refugees, fills her with more gratitude for her own life and the privileges she enjoys, And when I read what that journalist wrote it upset me because it seemed like she was showing compassion for refugees but she wasn’t. She was thinking of herself. She was seeing refugees as unfortunate people and herself as a fortunate one. We know this view. It’s the one that continues to alienate us from the suffering of others. It’s the view of our parents telling us to eat our vegetables because there are starving people in Africa, as if our finishing the food on our plates could ever compensate for injustice.

I want to put forward a different view. I named my novel ‘How Fast Can You Run’ instead of a more poetical title. I want my book’s title to reverberate: this can happen to you, it can happen to anyone.

The word refugee is so pejorative the author Chimamanda Adichie, herself a refugee and a former student at Drexel, wrote an essay recently in which she said, “nobody is ever just a refugee. Nobody is ever just a single thing and yet today in the public discourse we often speak of people as a single thing, Immigrant. Refugee.” She proposes a new narrative, one in which we see truly the complexities of the people of whom we speak. Perhaps you are familiar with her Ted Talk called “The Danger of the Single Story.”

This year’s Pulitzer prize winning author, Viet Thanh Nguyen, recently published a really interesting essay in the New York Times called “The Hidden Scars all Refugees Carry.” In it he says that his Pulitzer prize winning novel The Sympathizer is not an immigrant story. He writes that he is a refugee who like many others, has never ceased being a refugee in some corner of his mind. “Immigrants are more reassuring than refugees because there is an endpoint to their story. By contrast refugees are the zombies of the world, the undead who rise from dying states to march or swim toward our borders in endless waves.” He says in this essay that he wants people to see those scars. He wants to proclaim being a refugee because there was a time when the world thought he was less than human and he wants to remind the world.

My grandparents, all four of them, were refugees thought they never used that word. They never spoke about their scars. Although all four of them were among the most spirited, buoyant and grateful people I know, they white-washed their pasts. As a result, I don’t know what town they came from in Eastern Europe or Russia or their original last names. I don’t know anything about the pogrom they escaped. I don’t know anything about the destruction that drove them out. I do know that they are heroes because if they hadn’t fled they probably would have been killed in the Holocaust and I would not be here today. My maternal grandfather came here when he was in his early twenties, so I am sure that he remembered his past, but he never spoke about it. And he died when I was in my early teens so I didn’t get the chance to ask. He spoke with a Yiddish accent but my parents didn’t speak Yiddish, so I never learned it. He ate borscht, soggy cornflakes with milk and stuck a sugar cube between his teeth when he drank his tea.

The day that I met those ten Sudanese refugees I felt like I was meeting my grandparents’ young selves. I’m not being relativistic here, I ‘m not saying that their experience is the same as someone from Sudan, but there are many commonalities. Michael fled his village in South Sudan at the age of five. He trekked, barefoot and naked, through a thousand miles through war zones to arrive at a series of refugee camps where he lived for a decade. When I met him and others who fled their homes and survived living in refugee camps, I found them to be in possession of a rare sense of optimism that I couldn’t help comparing to my own relatives who had escaped pogroms in Eastern Europe back in the early 1900s. Considering that they came from different parts of the world and experienced different traumas, this shared characteristic struck me as odd. Then I realized, this is what it takes to be a survivor—indomitable spirit—these are the people who survived.

In a deal brokered between the US and the South Sudanese leader John Garang, now deceased, (he died in a mysterious helicopter crash), Michael received political asylum to the States along with approximately 4,000 other unaccompanied minors, the so-called “Lost Boys.” The South Sudanese people I’ve met both in Philadelphia and in Juba display amazing courage and strength: a women with fist-size scars up and down her legs from slamming into trees as she escaped her burning village in the middle of the night; a man who still suffers debilitating gastrointestinal issues from having subsisted on the two-week rations of half a cup of oil, salt and grain, in refugee camps; a graduate student whose best friend was shot before his eyes for selling Bibles on the steps of a University in Khartoum and who escaped under gunfire, miraculously made his way to Philadelphia where four years later he presented his doctoral defense at a major University.

When I met Michael that day, he found talking about his experiences was so freeing that he didn’t want to stop and he asked me that very day if I’d write a book about his life. All that winter, Mike and I sat on my couch, our shoulders rubbing, the afternoon light changing to dusk as we talked about his life and his goals. He wanted to return to Sudan one day. He wanted to build a school. He wanted to work in the government and change things. The two of us were thrilled when Charter for Compassion chose our book, How Fast Can You Run, as its first education Global Read.

The Charter for Compassion is an international campaign to make compassion “a clear, luminous and dynamic force in our polarized world, (http://www.charterforcompassion.org). Joining is the very least anyone can do.

Harriet Levin Millan

Some parts of this article have already appeared in The Sisterhood blog, published in the Forward.

Next week I interview Anne Samson, co-director of TSL, a publisher going beyond the traditional publishing model.

ABOUT LESLIE TATE’S BOOKS:

Part 2 of my interview with Mark Statman looks closely at Mark’s Latin American poetic influences, his life in Mexico and ends with an extract

I interviewed international poet and translator Mark Statman about Volverse/Volver, his 14th published collection. Mark, who has won national arts awards, is Emeritus Professor of Literary

I interviewed Lisa Dart, finalist in the Grolier, Aesthetica and Troubadour Poetry Prizes and author of The Linguistics of Light (poems, Salt, 2008), Fathom (prose

I interviewed writer Julia Lee Barclay-Morton about her experience of autism. Julia began as an experimental dramatist in New York, moving to the UK to

I interviewed Gillean McDougall from Glasgow, who edited the collaborative projects Honest Error (on Charles Rennie Mackintosh and his wife Margaret Macdonald) and Writing the

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

4 responses

A very interesting post, Leslie. Quite a sad read for me right now with the current economic turmoil in South Africa.

Yes, I understand SA is a difficult place to be at the moment. The interview on Monday is with Anne talking about TSL Books and one of yours is pictured with a link to point of sale.

Many thanks for another fascinating post. I enjoyed reading this so much that I just downloaded the book!

I think it’s well-written. 🙂 🙂 🙂