Part 2 MARK STATMAN: MEXICO AND THE POETRY OF GRIEF AND CELEBRATION

Part 2 of my interview with Mark Statman looks closely at Mark’s Latin American poetic influences, his life in Mexico and ends with an extract

In this special guest post, John MacKenna, the winner of the Hennessy Literary Award, the Irish Times Fiction Award and the C Day-Lewis Award, was interviewed by children’s and adult novelist, Sue Hampton.

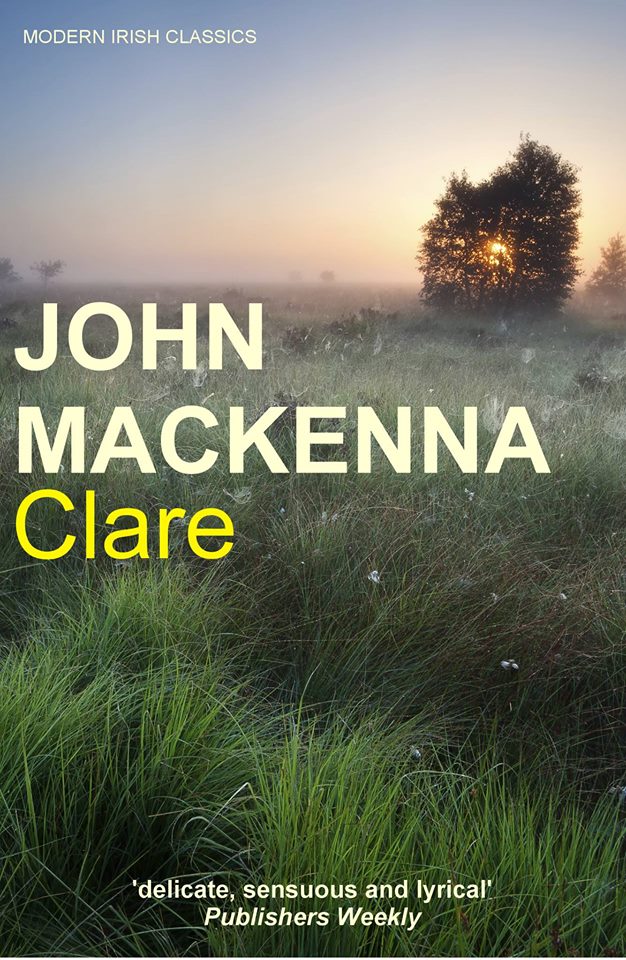

Sue’s introduction: Once We Sang Like Other Men is a new short story collection by award-winning Irish poet, playwright and novelist John MacKenna. I found it compelling, bleakly beautiful, sometimes disturbing and often deeply moving. The blurb says:

‘These wide-ranging stories follow the disparate disciples of the Captain – a mysterious, powerful and magnetic figure whose violent and chaotic death at the hands of the army radically alters their lives in myriad ways. From rural North American farms and dive bars to the suburbs of Ireland and the sands of Palestine, we witness their struggles to find a place, a peace, in a world that is fractured and incomplete.’

Some, reading this, will at once find Jesus. Many won’t. One might call this a modern, humanist reworking of an old story, or rather an exploration of the aftermath of the story for those who followed their master. We never know exactly what happened to the Captain or why, and I’m not sure it matters if readers fail to see the parallel. I’m a Quaker now but took a while, to use a Biblical metaphor, for those scales to clear. Then I wished I wasn’t reading on Kindle because there was a part of me that wanted to look back, compare and piece together. I concluded, though, that it was more rewarding to wonder, care and feel.

Sue, to John: Firstly, John, any comments on my response and suppositions? I’m guessing that you intended the book to be less of an allegory or puzzle than a study of damaged humanity post-trauma and possibly post-ideals.

John: Yes, my intention in writing the book was to explore the characters as people and, yes, the stories were inspired by some of the stories and some of the named characters in the New Testament. But I wasn’t attempting to rewrite the gospels – rather to look at the humanity of the people involved. The post-idealism of their circumstances, the losses involved were what interested me most.

John: Yes, my intention in writing the book was to explore the characters as people and, yes, the stories were inspired by some of the stories and some of the named characters in the New Testament. But I wasn’t attempting to rewrite the gospels – rather to look at the humanity of the people involved. The post-idealism of their circumstances, the losses involved were what interested me most.

Sue: The Captain is a shadowy, off-stage figure, many things to many people. When I create a character I tend to know more than I end up telling the reader. Do you see and hear him? Do you know the details of his teaching or his motivation, and how different or similar he is to Christ? Or is it essential that even for you, his creator, he’s clouded in many possibilities and contradictions?

John: Like yourself, I tend to know much more about any character in a story or book than I reveal. With The Captain, I knew his philosophy; I heard him and knew what he said but – just as I did in Clare, my novel about John Clare – I wanted the central figure to be missing. I wanted to hear about rather than from him. But I’m always intrigued by the sense of the absent and the untold in a good story or poem. The things unspoken, the anecdotes untold, the characters unseen really intrigue me.

Sue: The collection could be read as a comment on the intangible and subjective nature of truth within and beyond religion. But perhaps you always write believing it’s the role of the reader to interpret and imagine rather than receive a package. Do you consciously insert the gaps whatever you are writing?

John: I do insert the gaps. As in life, so in literature – the things that most intrigue me about people are the stories untold. The lives that are lived in parallel and the might-have-beens are fascinating. You see it in the lives of people – the moments when they said or didn’t say something and that moment changed their lives. As for the truth in religion – is there one, are there many, are there any? The characters in this book believed – totally – and the things they believed may have been true but they are left – in the wake of The Captain’s death – with an absence of leadership and certainty and belief. That’s an interesting place for a writer to mine.

John: I do insert the gaps. As in life, so in literature – the things that most intrigue me about people are the stories untold. The lives that are lived in parallel and the might-have-beens are fascinating. You see it in the lives of people – the moments when they said or didn’t say something and that moment changed their lives. As for the truth in religion – is there one, are there many, are there any? The characters in this book believed – totally – and the things they believed may have been true but they are left – in the wake of The Captain’s death – with an absence of leadership and certainty and belief. That’s an interesting place for a writer to mine.

Sue: You’re a humanist. Has your attitude to religion in any of its forms changed through your life and experience?

John: I grew up and went through college as a practising Catholic; then I went through a period of agnosticism. In the eighties I became a Quaker and now I would describe myself as an Agnostic Quaker. I attend meetings for worship and I listen and I learn but I’m not sure about many, many things. But after everything, the human figure of Jesus and his teaching intrigues and excites me.

Sue: How did this collection evolve? Did you begin with a single story that triggered eleven more, or did the concept of the book come as a whole?

John: A friend of mine said to me one wet, Sunday afternoon about twelve years ago – as we stood on the terrace at football match – “Have you ever thought that the disciples may have taken Jesus literally when he said: ‘Eat my body and drink my blood?’” I spent years thinking about it then wrote one story – Peter’s story – and it grew from there over a four year period. There are autobiographical elements in some of the stories, too, though.

Sue: I found these stories compelling but, like your poetry, achingly sad, both tender and dark. Did you feel this sadness when you write or do you achieve a craftsman’s distance?

John: I felt a sadness for these characters and my brother’s death seeped into the writing – and into some of the individual stories. I tend to write best out of the dark places in my memory and imagination and I tend to write mostly in winter – a time of darkness, too.

Sue: Is there a story that was harder to write than the others, and if so, why? Was there one that came to you whole, like McCartney’s Yesterday, and only needed recording?

John: Peter’s story came very quickly. I think because he was central to the ‘twist’ in the narrative. The story that was hardest was Say to Your Brother – because it’s the most autobiographical.

Sue: You have followed a poetry collection, When Sadness Begins, with these short stories, but are also known as a playwright. What’s next?

Sue: You have followed a poetry collection, When Sadness Begins, with these short stories, but are also known as a playwright. What’s next?

John: A requiem – more darkness – drawn from the songs and written words of Leonard Cohen and shaped with his agreement. The irony is that it’s now – in a way – a requiem for him, too. After that I tour a one man play I’ve written called The Mental – set in an Irish psychiatric hospital in 1990. I’m performing in that myself and being on the road is a break from the solitary life of writing – I enjoy that variety.

This interview appears simultaneously here on Sue Hampton’s blog, which explores writing, education and other passions.

Next week, in part two of her blog about creativity, TIGHT FISTS OF FEELING, Michelle Payette-Daoust writes about the themes of ‘otherness’ and ‘opening the door to suffering’ in blogs published on this site over the last three years.

ABOUT LESLIE TATE’S BOOKS:

Part 2 of my interview with Mark Statman looks closely at Mark’s Latin American poetic influences, his life in Mexico and ends with an extract

I interviewed international poet and translator Mark Statman about Volverse/Volver, his 14th published collection. Mark, who has won national arts awards, is Emeritus Professor of Literary

I interviewed Lisa Dart, finalist in the Grolier, Aesthetica and Troubadour Poetry Prizes and author of The Linguistics of Light (poems, Salt, 2008), Fathom (prose

I interviewed writer Julia Lee Barclay-Morton about her experience of autism. Julia began as an experimental dramatist in New York, moving to the UK to

I interviewed Gillean McDougall from Glasgow, who edited the collaborative projects Honest Error (on Charles Rennie Mackintosh and his wife Margaret Macdonald) and Writing the

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

4 responses

Thank you Sue, Leslie, for this discovery of a fascinating writer. I must admit that the pervasive sadness of his work that he himself acknowledges, draws me to his writing, but also leaves me hesitant to read him. What a disconcerting effect. I have ordered Once We Sang Like Other Men. The promise of beauty and mystery have won out.

I think you’ll admire the style and the depth of feeling.

A very interesting interview. I liked the sound of this book.

He’s a fine writer.