SARAH ROSS-THOMPSON AND THE ART OF COLLAGRAPHED PRINTS

I interviewed artist Sarah Ross-Thompson whose exceptional Collagraphed prints use fabrics, lichen, porridge and string to create images of the dramatic Scottish Highlands where she

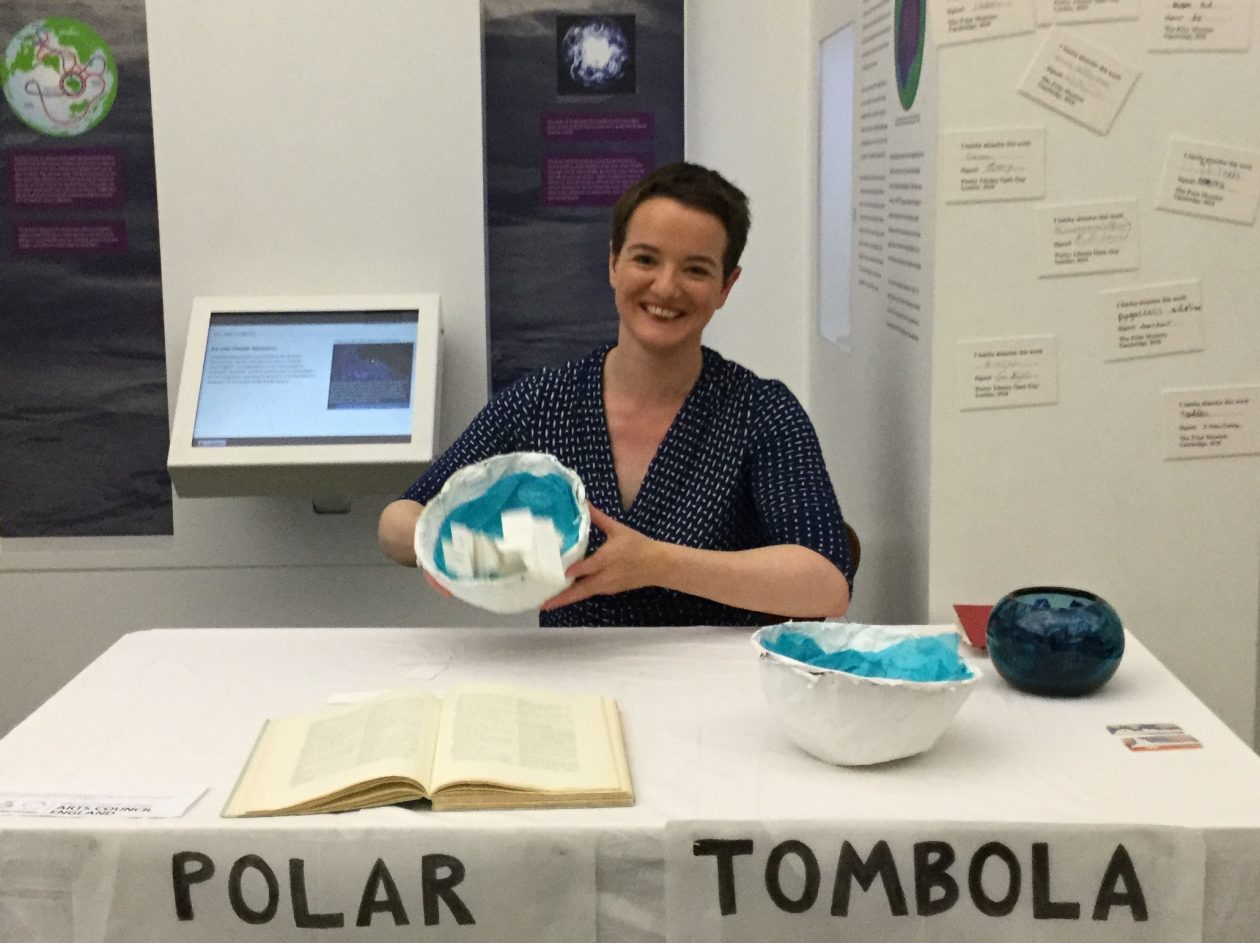

I interviewed poet, art critic and environmentalist Nancy Campbell about her Arctic residencies, her climate change projects, and her work supporting threatened cultures. Shortlisted for the Forward Prize Best First Collection, Nancy is also an innovative printmaker who has won the Birgit Skiöld Award. She was a Marie Claire ‘Wonder Woman’ in 2016 for activities including the Arctic Book Club and The Polar Tombola, an interactive live literature event. Nancy’s latest book, The Library of Ice, a blend of cultural history, nature writing and memoir, is published by Scribner UK.

Leslie: Can you describe your artistic residency with Upernavik Museum, Greenland, and how your encounter with this community has informed much of your subsequent work?

Nancy: I was invited to be Artist in Residence at Upernavik Museum in the winter of 2010. The expectation was to create a new work for the community during my time on the island. The intention was to respond to the anthropological collections in the small museum, and to the wider environment – the ice-filled expanses of Baffin Bay and the imposing mountains along the coast.

It was a great privilege to live among the community on Upernavik. I was warmly welcomed and the islanders I met supported my work as much as any of the objects in their museum. Since few of the islanders spoke English, I received some informal lessons in Greenlandic, and the language offered me many insights to the culture. I wanted my work to gesture to the uncertain future the islanders faced due to the rapid changes in climate and in society. As one example of this situation, in 2010 the national language was assigned vulnerable status in UNESCO’s Atlas of World Languages in Danger.

My interest in the language led me to create How To Say ‘I Love You’ In Greenlandic, a book I hoped would be equally accessible to the islanders and to my English readers. It is an alphabet book, but one aimed at adults, rather than children. In this dual English-Greenlandic work, the words illustrating the letters of the Greenlandic alphabet spell out a love story to the environment, and a narrative of the effects of climate change on individuals living on the ice edge. It was a challenge to see how few words such a story could be told in, but as a poet used to working in a compressed form, I found the challenge immensely exciting. Each Greenlandic word is accompanied by a hand-printed image of the icebergs which I saw during my time on the island.

Leslie: You trained as a letterpress printer and typefounder. Can you explain what that involves and the artistic work & collaborations it has led to?

Nancy: I left university following three years of studying English Literature wanting to know more about how the books I’d been reading were made. I was especially interested in the crafts that were used to publish books up until the twentieth century, in which the individual worker’s hand, and skilled eye, were still relevant.

At the time there were very few places to study traditional book arts. Eventually I found a master craftsman living up a mountain in the Canadian Rockies, who was willing to share his knowledge with me. I lived with Crispin Elsted and his family for a year, learning how to set metal type in a composing stick, how to handle ink and paper respectfully, and absorbing the principles of good book design. Although the studio was out in the woods, and very isolated from the modern world, many wonderful people made their way to it, such as the artist Abigail Rorer and the poet and type designer Robert Bringhurst.

Since that apprenticeship, I’ve been fortunate to work in letterpress print studios around the world and have collaborated on projects with a number of artists. This form of publishing words excites me – there’s so much opportunity for artistry. I feel strongly that if you care about what you write, you should also care about how it looks on the page. Making a book by hand is a slow process and inevitably connects the writer, and the reader, more closely to the words. One of the collaborations I am proudest of is a series of projects with the New York artist Roni Gross. She has created some highly imaginative artist’s books engaging all five senses in response to my poems.

Leslie: Can you describe your innovative literature projects to engage audiences with environmental issues, please?

Nancy: I feel very strongly about environmental issues, and I respond in the best way I can – through language. But I am all too aware that the message of many literary works stays within the arts world and doesn’t impact on wider society. I strive to find new arenas for performance and playful means of sharing ideas. This might be using an alternative publishing format, or creating public events that overturn the traditional model of the writer standing and reading for an hour to a silent crowd in favour of more egalitarian approaches.

For example, I created The Polar Tombola as a participatory art project that encouraged people to empathise with the experience of speakers of endangered languages. While learning Greenlandic, I realised that the detailed vocabulary for objects like ice enshrines much traditional knowledge about the environment. As the vocabularies of endangered languages diminish, this may affect people’s ability to speak about nature, to understand it, and thus to preserve it. The Polar Tombola was set up at events around the UK as a game during which I asked people, ‘If you had to lose one word from your language, what would it be?’ The question prompted many thought-provoking conversations about language, self-expression and censorship. Common words discarded included ‘Hate’, ‘Sorry’, ‘Like’ and ‘Tory’. I was surprised by how many people wanted to banish words for political parties or movements they disagreed with, and sometimes I challenged the speaker: do you not need to keep the word in order to fight the concept you oppose? All the words people offered me were carefully collected and published in an anthology The Book of Banished Words, alongside newly commissioned works by poets, writers and artists including Will Eaves, Vahni Capildeo and Phil Owen.

I hope my work can contribute to developing people’s love of language and sense of intrigue in learning about the world. I love reading books about the Arctic and to share that pleasure I set up a book club a few winters ago. Originally meeting around the fire in a small second-hand bookshop in Oxford, it’s now developed into an international group that comes together online – you can follow on Twitter: @ArcticBookClub.

Leslie: What have been the stand-out moments from your Canal Laureate work? How has it shaped your writing and what have you learned from it?

Nancy: It’s been an incredible year working with the Canal and River Trust and The Poetry Society to spread the word about the waterways. I have used the Canal Laureate role as an opportunity to write about my experience of the canal network as a kayaker. My interest in the sport meant I was already familiar with the waterways and was able to access them for research easily – and at mallard-eye level. I’ve loved every excursion, whether an outing for fish & chips on the calm Kennet & Avon Canal in Bath, exploring the wide and silty Ouse flowing above York, or a community canoe litter-pick on the River Lea in East London. However, the highlight has to be the week paddling the Leeds & Liverpool canal, the longest in the UK, and talking to those who live and work along it.

One of the ways it’s shaped my writing is through the commissioned poems. The Canal and River Trust might provide a specific subject. For example, a poem was requested about rain, which will be painted onto towpaths in hydroponic ink (which only shows up when it’s raining); another about a shy species of fish which lives in the Severn estuary. I’m sometimes asked for poems to celebrate particular sections of the canal, in Milton Keynes and Nottingham for example. When writing for myself, I’m often tempted to wait for inspiration to strike, but with a commission I know I need to discover that spark within the chosen theme. It is an incentive to look even more closely at the world.

Usually, I tend to write many drafts before I’m satisfied with a poem, leaving time between each for the words to settle and become unfamiliar. Due to deadlines during this residency, I have learnt to write quickly and impulsively, and let the work go when it’s still freshly made. This was hard to reconcile myself to at first, but I’ve found it very liberating. And in some cases impressionistic results were desirable! For example, the text I wrote for films created by the artist Pierre Tremblay, The Cut and Gastower Park, about the Regents Canal, needed to echo his impetuous, energetic narrative.

Leslie: You’ve a poetry collection, art criticism and narrative non-fiction. Which do you enjoy most, and why?

Nancy: One of the most enjoyable areas of my work is writing about art; my father was a sculptor and art historian, and my mother a weaver and painter, so my first understanding of the world was visual. I’m fascinated by the highly individual ways artists present their ways of seeing the world, and finding words to describe this is a wonderful challenge. In the last few years I’ve written essays for catalogues, such as Bill Jacklin’s exhibition at the Royal Academy, or on the prints of Louise Bourgeois, Francis Bacon and Lucien Freud at Marlborough Fine Art. I’m particularly interested in artists who respond to polar landscapes – something I cover in my book The Library of Ice: Readings in a Cold Climate. The beauty of icebergs and glaciers is so hard to recreate in any medium, and I’m deeply curious about the work of those who attempt it.

Leslie: Finally, what have you learned from your travels and artistic/writer’s residencies?

Nancy: I’ve learnt that the best experiences (in poetry and on the road) happen when the journey goes awry. I’ve learnt how to accept hospitality, and how to give it. Above all, I found my voice. There’s an Icelandic saying, ‘The visitor sees things with a clear eye’. While it may be true that we observe unfamiliar terrain with the fewest impediments, I also believe travel has helped me to know my own all-to-familiar self far better…

Next week I interview independent film-maker Molly Brown, winner of the Golden Trellick Award at the Portobello Film Festival.

ABOUT LESLIE TATE’S BOOKS:

I interviewed artist Sarah Ross-Thompson whose exceptional Collagraphed prints use fabrics, lichen, porridge and string to create images of the dramatic Scottish Highlands where she

Part 2 of my interview with Mark Statman looks closely at Mark’s Latin American poetic influences, his life in Mexico and ends with an extract

I interviewed international poet and translator Mark Statman about Volverse/Volver, his 14th published collection. Mark, who has won national arts awards, is Emeritus Professor of Literary

I interviewed Lisa Dart, finalist in the Grolier, Aesthetica and Troubadour Poetry Prizes and author of The Linguistics of Light (poems, Salt, 2008), Fathom (prose

I interviewed writer Julia Lee Barclay-Morton about her experience of autism. Julia began as an experimental dramatist in New York, moving to the UK to

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |