SARAH ROSS-THOMPSON AND THE ART OF COLLAGRAPHED PRINTS

I interviewed artist Sarah Ross-Thompson whose exceptional Collagraphed prints use fabrics, lichen, porridge and string to create images of the dramatic Scottish Highlands where she

I talked to Vici Wreford-Sinnott, Artistic Director of Little Cog, a disabled-led theatre company and Creative Lead of a disabled-led arts programme called Cultural Shift. Both are based at Stockton Arts Centre.

Vici, who has written, directed and toured numerous plays, says of her work: “Anyone working in socially engaged work, in work that is a call to arms for equality in the arts, and particularly anyone working in Disability Theatre feels both a sense of responsibility to ‘get it right’ and also to create a piece of work that stands on its own artistic merits. Anyone making theatre does so because they want an audience to have a fantastic experience, and to see an exemplary piece of work. Even 27 years into my career, it always feels like so much rests on the work. Broadly in wider arts, there is an unspoken fear that disability work brings extra risk with it – ‘will people want to see it, will it be any good, does it have a place in our building’.”

Leslie: How did your own love of theatre begin, grow and develop? On that journey, what have been your greatest learning experiences?

Vici: I’ve been thinking about this a lot lately – how does a girl from a small farm outside a County Durham pit village end up working in theatre? It was a fairly culturally conservative place and theatre was not a regular fixture in our lives by any means. There was an annual pantomime and there was one school play where I played third urchin from the left in Oliver Twist. I made shows with my childhood friends – usually containing lots of dance numbers – and I sang songs to unwitting audiences of cows. Their big brown supportive eyes made them a fantastic crowd.

My earliest memories are of extended family gathered around a kitchen table telling stories, the air ringing with laughter. My cousin Ali and I used our childlike imaginations to create wonderful escapist worlds that we’d play in for hours. So early ‘theatre’ experiences for me were all about people, all about connectedness and sharing, whether it was the laughter at pantomimes, in family tall-story telling, or in inventing new experiences. And then punk rock hit my world and I loved the theatre of exhibitionism, the costumes, the thinking, the anti-establishment politics, and exploding the status quo.

My theatre is informed by those early things – people, connectedness, new worlds and possibilities, not taking things at face value, and creating visually striking aesthetics with iconic soundtracks. I moved to London as a punk teenager and in the thick of gigs and underground clubs, I went to see Steven Berkoff’s Metamorphosis starring Tim Roth which blew my mind. It literally blew my mind – I couldn’t sleep that night and it occupied my thoughts for weeks. That you could take so many of the things that interested and excited me and put them in one place to share with other people had a massive impact on me and set me off on a journey towards discovering an electric world full of women writers and theatre makers, and politically explosive work.

Leslie: What are the characteristic forms of drama you put on at Little Cog?

Vici: My aim has always been to create beautiful, powerful and thought-provoking live works of art, which are widely accessible to as many people as possible, and where a special energy is created between performers and audience. I now realise looking back, that this comes from a direct line to my early days in punk. As a disabled woman who doesn’t see herself or my disabled community represented in most drama, other than in stereotypical ways, I decided it was important to create stories which address that, both for me and for other disabled people.

Most of the work we make is live theatre and is contemporary, relevant to our world, lively, funny and dark. We shine a light on lesser told stories and stories which have been mis-told. The characteristics of the work tend to include powerful untold stories full of heart and humanity which examine who we are as a 21st century society and how we treat each other. We offer interventions into the status quo of dominant arts which disrupt common thinking and perceptions about our world and who holds power. Our work is highly visual, physical and always has amazing music.

In addition, an important strand of our work has always been a commitment to learning disability culture and theatre, our mission being to put all disabled people centre-stage, and so, Little Cog also has the pleasure of being key artistic collaborator with Full Circle, an ensemble of learning disabled theatre makers, who create original work on a main stage scale. We also have new partners Stockton International Riverside Festival (SIRF) and so we are upping the scale further to outdoor work. And our aim is always to be entertaining and thought provoking in ways that bring about change.

Leslie: Could you tell me about the special qualities that disabled actors bring to performance, please.

Vici: Well, disabled actors are as varied and different in their artistic talents and interests as non-disabled actors are and we probably wouldn’t describe ourselves as having special qualities but perhaps specific qualities. It’s essential in disabled-led theatre that the work is created and delivered by disabled people who are aware of our cultural heritage, and have experience of both the disabling impact of society, and the solidarity and history shared by other disabled people. Our vision is to fill the world with stories from this world as they have been hidden from our history books and history lessons as irrelevant.

If there is a disabled character in a story, in my opinion, they should always be played by a disabled actor – it’s not possible to ‘fake it’ due to the historical and social contexts disability exists within.

Disability isn’t the impairment or condition presented in and of itself, for example a blind character, it’s not possible for a non-disabled actor to convey that with authenticity other than to suggest a surface, and again stereotypical representation. Disability is a multi-dimensional social phenomenon which only disabled people experience and understand.

It’s really important that disabled people see ourselves represented on stage or in TV and film with rich expression and certain knowledge. There are some characters and performances of disability by non-disabled actors which are toe-curlingly bad to watch, including Daniel Day Lewis in My Left Foot for which he won an Oscar, Dustin Hoffman as Rain Man and Tom Hanks as Forest Gump to name but a few.

Of course, as disabled people, we must not be defined by our conditions and so then there is another layer – what happens, in a far-off future when it becomes routine to cast disabled actors, not just as disabled characters and not as metaphors for struggle, but to interpret older work in new ways, and even to cast disabled people in iconic roles where their condition isn’t the defining factor but the beauty and power of the work they do is. Disabled-led companies are doing amazing explorations into such work and we have seen other non-disabled and national companies following suit.

Leslie: What is the reason for the company’s name?

Vici: People have speculated about the name of the company, Little Cog, over the years, and there is the initial impression of little cogs making big wheels turn – thoughts of a small but mighty company making a difference, unafraid to speak up, speak out, and to be bold in a massive mangled web known British arts and culture.

Those things are true, but actually the name Little Cog is the name of one of my favourite characters from the feminist canon of theatre, from the play Ironmistress by April de Angelis. I don’t think I’ve had the opportunity to fully acknowledge this before but I love that play and what it means to me. I directed it as one of my degree shows when I trained as a director at the University of Kent. It was pivotal for me to find a play, written by a woman, that was multi-layered and telling stories on so many very clever levels; society, history, feminism, female relationships, capitalism and was just so vibrant and vital. It tells the story of Martha Darby, a powerful woman who inherits her husband’s iron foundry in Victorian Britain, and her daughter, Little Cog, on the eve of her marriage to someone she does not love. It is written in verse and is as playful as it is dark. Little Cog is forced to question the role society has carved out for her in female servitude, and her journey exposes just how constructed our identities are by society. As a young theatre maker many years ago, this play represented many turning points for me, not least on knowing the kind of challenging and vital work I wanted to make. The character of Little Cog is a source of strength for me.

Leslie: Little Cog theatre company is disabled-led. What does that mean in practice for disabled and not-disabled actors working together? What has been learned on both sides?

Vici: When I set up Little Cog it was about creating a new working environment, and new working space to explore and experiment with precisely what is needed to have an accessible practice which focuses on disability equality. Our work is disabled-led which means that the decisions around the work we make are taken by disabled people – that dramatically changes the landscape of a rehearsal space.

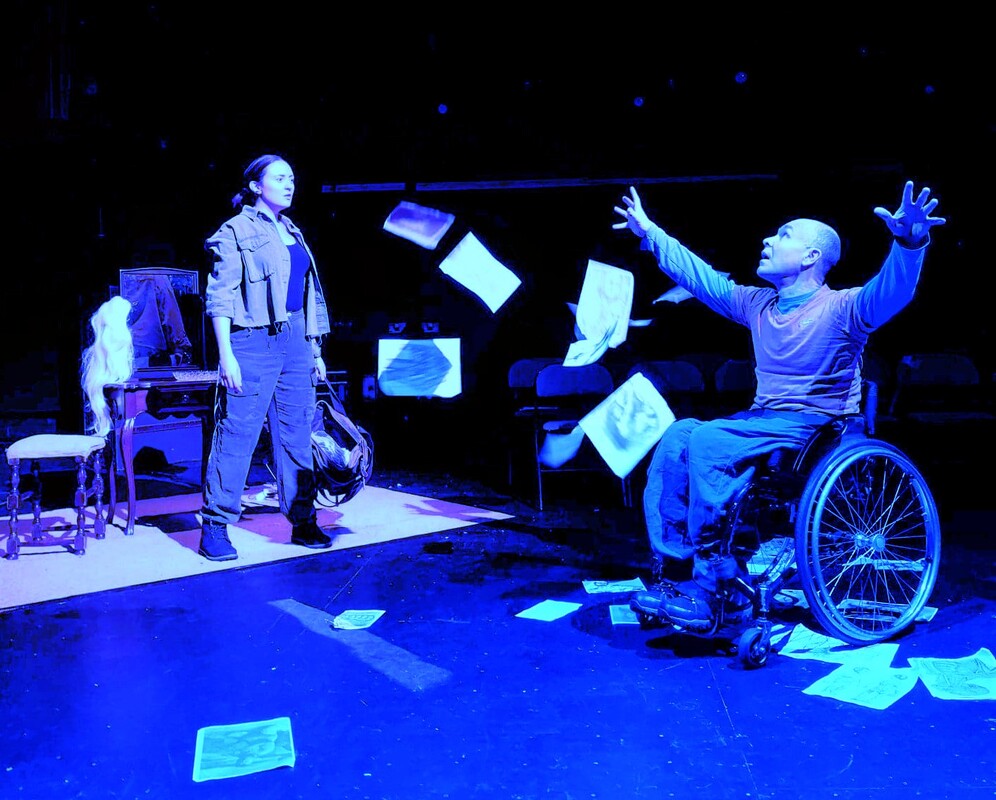

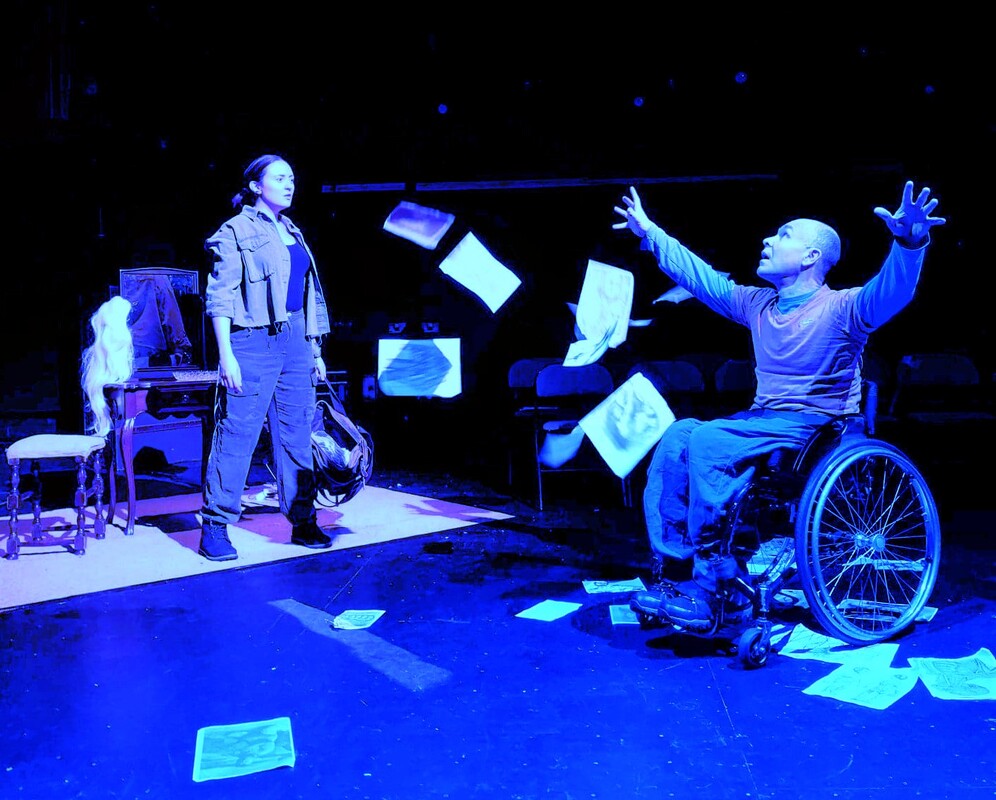

The stories we tell focus on disabled characters and our emphasis is putting disabled stories, characters and actors centre-stage – something denied to disabled people for too long, and still the status quo for us today. We don’t set out to put disabled and non-disabled actors together unless the story calls for it. One piece of work where that did happen was our production of Occupation by Pauline Heath which tells the story of four unlikely street protestors, who feel forced to take part to ensure their stories are told around the austerity measures and benefits cuts of the Tory government. There is a disabled army veteran performed by a wheelchair user, a lost youth performed by a Deaf actor, a professional disabled woman performed by a Deaf actor and a non-disabled parent of a disabled child performed by a non-disabled actor. We also had a 12 strong community chorus which was a mix of disabled and non-disabled people. It was a political piece of work, illuminating on a number of levels for everyone involved.

The content revealed how cuts to disability services affect people’s lives, personally and politically, and in fact how it damages the wider economy. Our practice in the rehearsal room is accessible and this means creating a new process, or a new version of accessible practice each time we work with new disabled actors.

There are the access measures we commonly use – advance planning for accessibility, budget lines for accessible rehearsals for the team, and also to make the work accessible to audiences. Our rehearsal rooms and performances have BSL interpreters, audio description, touch tours, stage captions, relaxed audience features, accessible information, marketing and programmes, content trigger information among other things, and easy read information for learning disabled people. In terms of where we work – we always ensure we have lift or level access, that we have enough time to develop the work, with quiet spaces actors/company members can retreat to for rest periods. And we have a policy of not touring or running workshops in inaccessible spaces – so for example we wouldn’t dream of running a playwriting workshop or presenting a show in a space where the only access was up a flight of stairs. It has to have access for everyone or not at all – we leave no-one behind. But really, access measures are simple technicalities that 25 long years after the Disability Discrimination Act (1995) should be just that – automatic features that we shouldn’t still have to fight for. Though of course we do, and much non-disabled work is not aware of this, is regularly presented in exclusionary spaces.

The other important thing that comes with disabled-led space, and doesn’t in other spaces, is a shared knowledge of experience – we don’t assume each other have deficits or things we ‘can’t do’. We might not know the intricacies of each other’s conditions, but we do know what it is like to be discriminated against and excluded on a daily basis, and we do know and share histories of the disabled people’s experience. We are able to discuss access and disability comfortably and free of fear of judgement, or having to explain, apologise for the inconvenience of us, or justify what we require. There is an understanding of where each other is coming from, and its not a space where we are forced to become educators, in addition to our artistic role, to help non-disabled peoples’ processes. The practice of disabled-led work then becomes a model of excellent practice.

As a disabled-led company we generally work in non-disabled dominant spaces, and so part of our work as a company is to work in partnership with venues and organisations to support them to better understand disability equality and access. We love working with allies who immediately get where we’re coming from and who are committed to bringing about their own education and organisational change to better involve, support and programme the work of disabled artists. An excellent beacon of hope in this regard is ARC Stockton, which is where Little Cog is based. It feels important to say it is a place of safety, and sometimes I wonder if only disabled people will know what that means. We feel unconditionally welcome, valued and equal. Spaces like that are incredibly rare.

Leslie: How are disabled arts activists extending the range of artistic expression offered through ARC Stockton and @Disconsortia?

Vici: This is a beautiful question as the answer is full of positivity, creativity, solidarity and opportunities to lift each other up. I always say that our cultural jigsaw is incomplete without all voices, and therefore is not a true reflection of our nation or world. The work of disabled artists at ARC expands all of our experiences and contributes to a fuller picture, a more complete jigsaw.

My partnership with ARC Stockton began in 2011 when I set up Little Cog on my return to the arts after a period of ill-health caused by burnout, wanting to focus on my own creative practice. The previous ten years had been filled with being CEO of Arts and Disability Ireland in Dublin and then CEO of ARCADEA in the North East of England – all fantastic work of a strategic and development nature championing disability equality in the arts, with only little pockets of time for creativity.

Time had ticked along and tricked me, and I felt that I had lost time to make up for and no time to lose as a practitioner, and so I approached Annabel Turpin, the highly inspirational innovator, CEO and Artistic Director of ARC, to chat about making my own piece of theatre, and honestly the response was life changing. I was welcomed, valued and supported. We did a number of projects together and then formalised our partnership for a three year strategic artistic project called Cultural Shift.

It was a multi-strand project, funded by the Spirit of 2012 Trust, which meant we could provide over 1000 participatory opportunities for disabled people from the local community, we created three pieces of community theatre, provided four disabled artist residencies supporting them to create new work. I was commissioned to create three new pieces of professional disabled-led theatre, two of which toured nationally to great critical acclaim.

And all the while, I was supporting ARC to shift its knowledge, understanding, policy and practice about working with a disability equality ethos in mind, with art and artists at its centre. Over 20 pieces of very varied work by disabled artists were programmed at ARC and they have now seamlessly embedded this into their usual programming practice. It was a learning experience for all involved but it was incredible – fulfilling, nourishing, challenging and new.

The legacy of that incredible three years – well, it’s multi-layered, like all the best things are. Programming and supporting disabled artists is just a totally natural part of life at ARC. Little Cog and Disconsortia are now based there and ARC are continuing to support me as an Associate Artist. Before lockdown, they were supporting me to make two new pieces of theatre, a large scale piece of street theatre with Full Circle and a series of opportunities for disabled artists, writers, actors and comedians to take part in. We’ll pick this up again once we have our bearings for a future after Covid 19.

And Disconsortia is another source of immense joy in my life. 18 North East disabled artists have formed a collective to a be a source of support to each other and to be a voice for equality in the arts in our region and beyond. Before lockdown we had held several events including an amazing DIY cabaret night, and some discussion forums. We also became an influencing voice when emergency responses within the arts were being formulated. We have big plans for future activity and have secured emergency funding from Arts Council England to consolidate ourselves and our plan, whilst also being able to award nine mini-commissions to disabled artists. All of that will be coming very soon.

Leslie: What are the internal barriers facing a disabled person in the arts? Can you describe any particular experiences of how this mindset can change?

Vici: For me, with the luxury of having spent almost thirty years having tried to bring about change, there are two main mindsets that we need to change – firstly, our own as disabled people and how we view ourselves and our status, and secondly, that of the arts systems in place in this country. I saw someone write a list of five things to challenge as we move through the covid-19 crisis and top of the list was inaccessible venues. I’d go a bit further and say we need to challenge inaccessible venues led by inaccessible people with inaccessible mindsets. Our national psyche has been to assume there is a central ‘norm’ on the periphery of which are smaller ‘minority groups’. By describing people as a minority, we’re already at a disadvantage but it also stops us seeing society as a pluralistic mix, not a melting pot, but where people are beautifully distinctly different but equal parts of the whole. The central ‘norm’ is a myth but because it is so entrenched it is very hard to challenge, and when you do, you’re always positioned as someone shouting from the edge. There really does need to be careful examination, involving disabled people in leadership roles, about how we meaningfully challenge our structure, but it certainly involves removing all existing barriers, increasing accessibility and access measure, embracing and valuing the stories of disabled people and shift in perceptions and projections about disability.

Disabled artists and activists are part of a fifty year long civil rights movement which has gone through a number of natural, organic and cyclic growth, with changes of emphasis and focus. Several things have coalesced over the lifespan of the campaign to make our movement stronger – disability rights activism, the disability arts movement, disability research and disability studies, cultural and critical analysis, and changes in the law. However, throughout all of this, as disabled people we are always pitched against an unmoveable monolith of ‘normality’, to which we are always a deficit.

It is very difficult for oppressed people not to internally absorb, perform and enact being an oppressed person. Through the strength and solidarity we can give each other, for the few short years each of us has a life on this earth, we need to shift this internal position and give ourselves, individually and as a community or as a social grouping, a different starting position. Easier said than done but something to think about.

Next week I interview Karen Eisenbrey who writes fantasy, sci-fi and drums in a garage band, writing songs for her debut YA novel .

I interviewed artist Sarah Ross-Thompson whose exceptional Collagraphed prints use fabrics, lichen, porridge and string to create images of the dramatic Scottish Highlands where she

Part 2 of my interview with Mark Statman looks closely at Mark’s Latin American poetic influences, his life in Mexico and ends with an extract

I interviewed international poet and translator Mark Statman about Volverse/Volver, his 14th published collection. Mark, who has won national arts awards, is Emeritus Professor of Literary

I interviewed Lisa Dart, finalist in the Grolier, Aesthetica and Troubadour Poetry Prizes and author of The Linguistics of Light (poems, Salt, 2008), Fathom (prose

I interviewed writer Julia Lee Barclay-Morton about her experience of autism. Julia began as an experimental dramatist in New York, moving to the UK to

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

2 responses

Thanks for the introduction to Vici, her work, Little Cog, and all the initiatives she is involved in. Powerful stuff and a great interview. I wish them all good luck in their projects, and I hope to hear about many similar groups and see them perform in the future. (And I do love cows!)

Thanks, Olga. ?☀❤ Leslie x