Part 2 MARK STATMAN: MEXICO AND THE POETRY OF GRIEF AND CELEBRATION

Part 2 of my interview with Mark Statman looks closely at Mark’s Latin American poetic influences, his life in Mexico and ends with an extract

I interviewed two prolific graphic novelists, Sandra Marrs and John Chalmers, who are Metaphrog, Together they have been creating comics and graphic novels since 1996. Metaphrog were winners of The Sunday Herald Scottish Culture Awards 2016 Best Visual Artist; they also have three nominations for the Eisner Awards (the Oscars of comics).

In Part One, Sandra and John talk about the techniques and creative methods that led to their early successes, including linkups with music.

Leslie: What lies behind the choice of the title ‘Metaphrog’ for your graphic novel work?

John: Back in 1994 we felt it would be a good idea to have a name that went out into the world a little like a group or a band. Something genderless, so that people didn’t know whether we were a girl or a boy or how many heads we had.

Sandra: We had been thinking and talking about a possible name. Like sulphurous frog and then Metaphrog just sort of popped out there.

John: We liked the idea of using a “ph” for the spelling because it echoed with phone phreaking.

Leslie: Where did you learn your storyboarding/artistic skills from?

Sandra: I am self-taught, and although I studied in France at art school I didn’t actually learn formal storyboarding techniques there nor did I learn drawing skills. Like all small children I drew and at the age of around 11 my friend lent me her ‘How to Draw’ books. So that’s when I took up drawing more seriously and started to really practice and improve. In France growing up, I read a lot of comics as well as classic literature and also studied painting (by myself). Comics are recognised as the 9th art there and as such are a huge part of the culture.

John: I studied engineering and science at Strathclyde University in Glasgow for almost a decade. My main passion is music and, growing up, I always read literature and had an interest in art, particularly painting and film. I think we both feel that an education is a good thing to have, anyway – and not necessarily because it would lead to a career. More just an education for its own sake. We were both lucky enough as young people to read and, even though we grew up in different countries through different decades, we both read a lot of the same comics. When we met we talked about comics we enjoyed – I love Zippy the Pinhead but also Oor Wullie. Sandra was drawing and painting and taking photographs and had just moved to Glasgow. I had always dreamt of being a writer, so it seemed natural to combine our passions and make comics together.

Leslie: When working on novels what are the key steps in the process?

John: Our working process is always slightly different, but some things stay the same. We always walk and talk about the key story ideas, the main themes and how best to treat them. Then I’ll settle down to writing. Making notes and researching as well as finalising pages of script. We usually find ourselves compelled to work on certain ideas. Sometimes they have been incubating for a while. Working on scripts for graphic novels I always try to create something with a novel aesthetic structure. Wanting the comic to be taken seriously, to stand up against works of literature (illustrated or otherwise). We have always both firmly believed in comics as an art form in their own right.

Sandra: I start to work on a few sketches – a book doesn’t really come to life for me until I’ve nailed the characters. For a new book project or comic, I’ll take the script and read it carefully, before turning it into pages of layout or dummy. These are really rough versions of how each page will look with the panels pencilled loosely. These roughs can go through several revisions as all the image (panel and page) composition and, to an extent, scene pacing is decided at this stage (as well as in the initial script writing). And, it allows us to both read the book carefully and decide if we’ve solved the challenges of a particular scene or indeed of the whole story as effectively as possible. It allows us then to walk and discuss everything and revise things, in the script or layout, where necessary before I invest a lot of time in making finished artwork. It’s a hidden and quite complicated part of the process and requires us to work closely together. Once we’re both happy with the layout I’ll then go to the drawing board and pencil out the art before inking and painting. Recently I’ve been working without inking so the pencils are directly followed by digital painting.

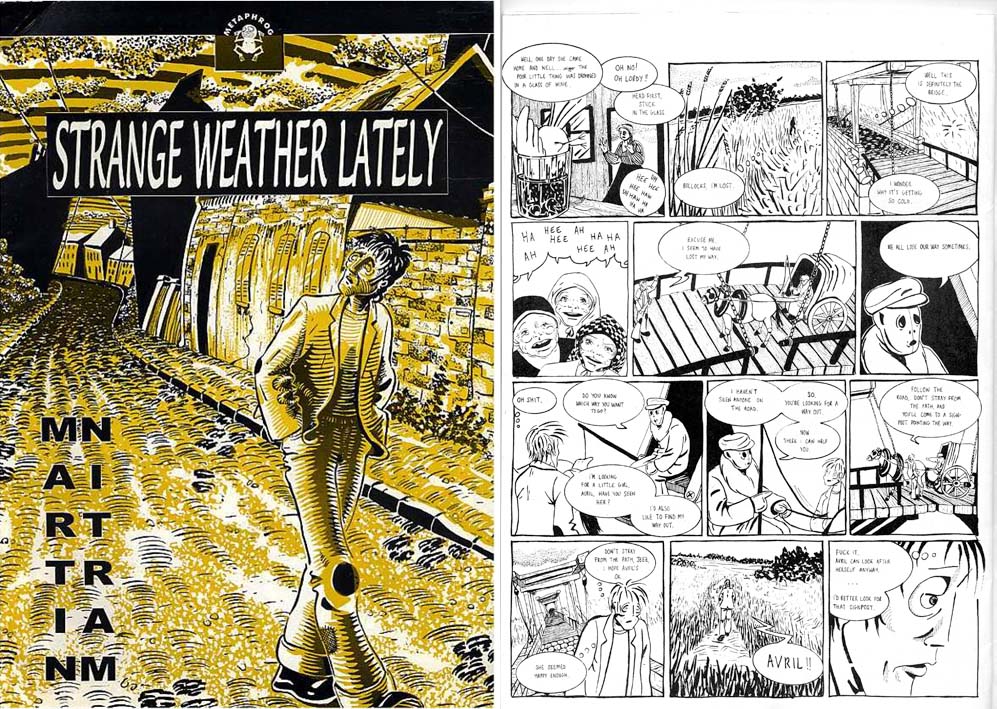

Leslie: In summary form, what was your first graphic novel ‘Strange Weather Lately’ about? What went into creating it and what did you learn from doing it?

John: Strange Weather Lately was created in the mid to late 90s, and is a mixture of social realism and surrealism centred on the failed attempt to stage and perform a cursed theatre play, The Crimes of Tarquin J. Swaffe. It is set in a fictional Glasgow and the story is built in layers of roughly concentric circles with characters and ideas migrating between each. The main theme of loss manifests as a loss of distinction between the layers as well as in the loss of what we felt were important values necessary for a happy and healthy society. We were upset at the ills of the societies around us: excessive consumerism; the toxic culture (for example, media that presented complex things as black and white); lack of employment possibilities; the cheap drugs and destruction of communities. We felt that exposure to a toxic culture was making people ill, creating mental health issues.

Sandra: The story was painted in a grey wash and serialised in comic form before being collected as two graphic novel volumes. The serialisation suited the fragmented nature of the story and the grey wash allowed us to show things as being less black and white and also to have the story fade away (as everything is lost) at the end. We learned a lot, both about working together and about the comic world and the fact that there was a comic industry. Working to deadline to have the comic ready for the distributor’s catalogue every two months meant establishing a very disciplined work rhythm and making a cover and designing the layout of each comic around the story every eight weeks. We used the extra space around the colour covers to make bookmarks and enigmatic flyers with coloured versions of weird images from the comics. It was good fun but a lot of work.

We travelled to America and France to visit comic festivals and comic conventions building industry contacts and strengthening relationships that had started by mail through the exchange of comics and fanzines. We printed locally, at Clydeside Press, and sent all ten issues of Strange Weather Lately out for review around the world and often received comics or fanzines and magazines in return. We also raised funds through sponsorship from the local community and did that every two months. It’s not always easy to say what we learn from something at the time but one thing we realised was that we wanted to make a book rather than more comics and we also wanted to create something suitable for all ages.

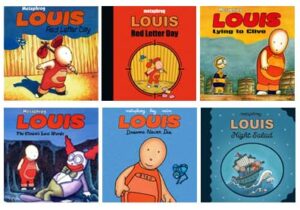

Leslie: What’s the blurb for ‘The Louis Stories’? Why did you create them and how did they take forward/ extend your skills?

John: We made a blurb in 1999 for the first paperback edition of Louis – Red Letter Day which was ‘scary-cute’. The book was designed to frighten and amuse children of all ages. Louis – Red Letter Day follows Louis and his friend FC (short for Formulaic Companion) and Louis’ attempts to live his dreams. We examined a lot of the same obsessions and preoccupations we had in Strange Weather Lately, including the importance of communication, friendship, and of having a role in society. In the background the careful reader will find ideas about the environment, ecosystems, pollution, surveillance, isolation, and the way we treat other creatures.

Louis – Red Letter Day was very well-received. Initially getting rave reviews in America – then being nominated for two prestigious industry awards, the Eisner Awards. When we sent red letters to the media in the UK with the US reviews then the book got positive reviews in places that didn’t usually feature graphic novels including style magazines like i-D and New Internationalist. Julie Burchill even wrote a column about it in The Guardian.

We also realised we’d fallen in love with the Louis character and wanted to keep making Louis stories. So Louis – Lying to Clive has a look at our inegalitarian world particularly the way we treated and treat the (former) colonies and explores the idea of language as a prison. Louis makes friends with Clive on a bee farm. It’s quite clear that things are not quite right.

Louis – Lying to Clive again did very well and was received with great reviews. Our visits to two conventions in America (San Diego Comic Con and SPX, in Bethesda) brought our work to a much wider audience. But it was a strange time. We arrived in the US the day before the planes hit the World Trade Center. In fact the SPX show we planned to attend was cancelled at the last minute. Big Planet Comics helped us enormously by giving us the Mark Feldman Award, a travel grant that the Hernandez Brothers could no longer use, as the air space was closed.

At lot of what was going on then found its way into Louis – The Clown’s Last Words. It was also a book that addressed the idea of organised fun – a ninety-two-page book about a suicidal clown for children was probably not our most commercial move but this book was the first ever graphic novel to be funded by the Scottish Arts Council. And, it felt great to see graphic novels taken seriously by the literary world. Our blurb described the book as ‘Kafka for kids’. What the story really interrogates is the role of the artist in society. The titular clown appears quite late in the story and only when poor Louis lands on him with a honk.

Louis – Dreams Never Die took shape that year and the story is a sort of fever dream as Louis tries to visit his (possibly imaginary) aunt. This graphic novel came with music by hey (from Berlin) and múm (from Iceland).

And Louis – Night Salad was created just after my dad died. It’s not a big book about death for children, rather a book about the power of books and how they can transport or even transform the reader.

Sandra: All the Louis books are naturally linked, but each one stands on its own and can be read individually. And all the books were pencilled, painted and then inked by hand. Inking after painting was difficult as any mistakes at that stage ruined the painting! It felt like the right way to do things as we wanted to experiment with the feel of a children’s book while still dealing with fairly deep ideas and concepts. At first I painted using water colours and then progressed to using acrylic inks.

Leslie: What was different about the process of creating a music animation for FatCat?

Sandra: I had always wanted to see Louis moving so it was enjoyable to create an animation. It took about 6 months’ work to make 2 minutes of animation. Planning an animation chronologically is very different from composing pages for a comic or graphic novel. The animation was created digitally, drawing each image separately, frame by frame, on computer with very little or no morphing and so I was working with a mouse rather than a pencil, pen or brush. I gave myself a RSI – a sore wrist and stiff shoulder. But the animation was great fun to make.

John: It was also interesting to work with a record label and make friends with the musicians involved. Múm had been big fans of Louis – Red Letter Day so were more than happy to make a remix of hey’s track Dreams Never Die. The animation soundtrack is a different mix combining hey’s and múm’s versions of the track. And, we’d been in touch with múm’s record label FatCat from their very beginnings. So the project felt right and everything seemed to connect making positive circles. It brought our work to a much wider audience too. At the time we had talked of the project as a way of cross-fertilising between the worlds of music and graphic novels. People who wouldn’t normally read a comic but listened to fairly experimental music and vice versa. Múm were very popular too so the print run FatCat made was 10,000 and there were loads of promo cds with a little mini-comic that went out to different places all round the world.

In Part Two next week, Metaphrog talk about their updated fairy tales and the tradition of the graphic novel as an art form.

ABOUT LESLIE TATE’S BOOKS:

Part 2 of my interview with Mark Statman looks closely at Mark’s Latin American poetic influences, his life in Mexico and ends with an extract

I interviewed international poet and translator Mark Statman about Volverse/Volver, his 14th published collection. Mark, who has won national arts awards, is Emeritus Professor of Literary

I interviewed Lisa Dart, finalist in the Grolier, Aesthetica and Troubadour Poetry Prizes and author of The Linguistics of Light (poems, Salt, 2008), Fathom (prose

I interviewed writer Julia Lee Barclay-Morton about her experience of autism. Julia began as an experimental dramatist in New York, moving to the UK to

I interviewed Gillean McDougall from Glasgow, who edited the collaborative projects Honest Error (on Charles Rennie Mackintosh and his wife Margaret Macdonald) and Writing the

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |