SARAH ROSS-THOMPSON AND THE ART OF COLLAGRAPHED PRINTS

I interviewed artist Sarah Ross-Thompson whose exceptional Collagraphed prints use fabrics, lichen, porridge and string to create images of the dramatic Scottish Highlands where she

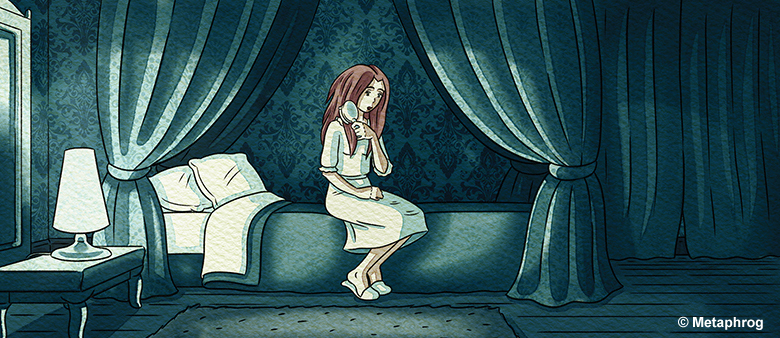

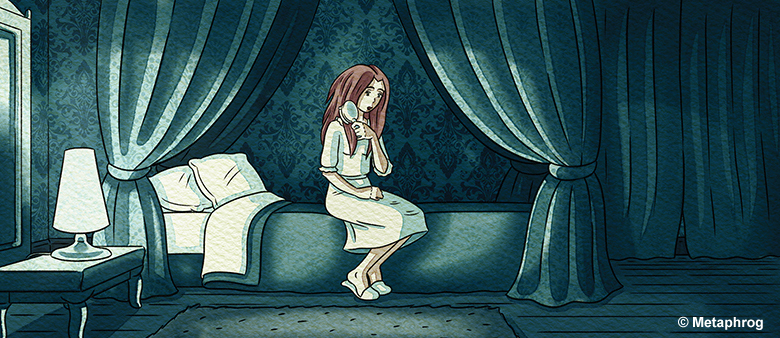

Part Two of my interview with graphic novelists, Sandra Marrs and John Chalmers covers the period when Metaphrog created subtly adapted versions of classic fairly tales. John and Sandra also talk in depth about the tradition of the graphic novel as an art form.

Metaphrog were winners of The Sunday Herald Scottish Culture Awards 2016 Best Visual Artist; they also have three nominations for the Eisner Awards (the Oscars of comics).

Leslie: Where does your interest in ‘radicalised’ fairy stories come from? What considerations went into updating these stories?

Sandra: We both grew up loving fairy tales – they made us excited, gave us horripilation, made our hair stand up on our arms and necks, and allowed us to suspend our disbelief. So, the interest comes from childhood. When I was little I had a record of The Little Mermaid – and could turn the pages to read while listening to the story. We felt like making these stories more modern, more personal, and also in comic form. Not sure if they are radicalised or not, although it’s fair to say that they probably would have been difficult to place with a traditional publisher. They are not Disney-fied versions!

John: So, some consideration was given to how best to adapt the tales – what kind of fictive world to construct. As an artist, or writer, it can be sometimes difficult to reach a work/life balance so The Red Shoes spoke to us. It resonated with us because we had been working most of the time and the story can be interpreted in that way. Most folk tales and fairy tales contain powerful messages that speak to us over time. Like ‘be careful what you wish for’, or ‘everything comes with a price’.

The darkness of the stories appeals to us. Fairy tales are always changing and evolving. We wanted our updates to contain an awareness of great woman writers like Angela Carter, Daphne du Maurier and even Patricia Highsmith. Writers who can create dangerous, morally ambiguous worlds. The ‘original’ Bluebeard tale by Charles Perrault is the opposite of feminism, so we wanted to change that message. The feminist idea is simply equality for women and men.

Leslie: How do you go about showing graphic horror?

Sandra: Sometimes it is better to leave a little to the imagination of the reader. With judicious use of framing and due consideration of colouring a lot can be inferred through heightened visual language.

I wanted to create a sort of magical feel to the tales and that can be set in contrast to the dark subject matter – the horror. Using bright colours, strong light/dark contrasts, colour coding as a storytelling device, in a way balances the darkness in the imagination.

John: We wanted to add depth to the world around Eve, our heroine in Bluebeard, to increase sympathy and empathy – so we had to write our own story or backstory that would contain our version of the myth. We hoped this would add to a sense of injustice and ultimately add to the horror when bad things start to happen to Eve. The final horror is conveyed visually through use of colour, composition, and layout or pacing.

Leslie: How have techniques for graphic novels changed over time?

Sandra: The techniques have changed over time along with the styles. If you look at superhero comics, they have used a very rigid style of storytelling and artwork. The underground cartoonists introduced a raw black and white style of artwork and autobiography that was more exploratory and experimental. Graphic novel techniques and vision were pushed further in the 80s and 90s. With the ascendance of manga imports, anglophone comics started to incorporate some of their techniques. And in the last 15 years, with the ascendance of graphic novels, the stories have become longer, and pages have become less visually compact, thus easier to assimilate for non-comic readers. People also started working digitally, although there also is a resurgence of the use of traditional media in more literary graphic novels for example.

John: Technology is less expensive and printing costs are also cheaper so lots more people are making comics. And print on demand has meant less risk or investment in making the physical comics. Some people are even making graphic novels, although the amount of work involved makes them more of a challenge.

Leslie: Who are the key people in the history of graphic novels – why them, what’s special/innovative about what they did?

Sandra: We’ll try to answer that question succinctly so it will focus on a few examples – one could write several books about that! In France the graphic novel world has grown fairly naturally from the world of Bande Dessinée, so as well as the Asterix creators Albert Uderzo and René Goscinny and Tintin creator Hergé, there are many artists in the French graphic novel canon including those mentioned above, Bilal, Tardi and Hugo Pratt but also people like Jean Giraud / Moebius. Each has a unique idiosyncratic style.

John: In the Anglophonic world the term graphic novel was coined by Will Eisner – and he created several graphic novels himself as well as comics with his character The Spirit. He talked of the importance of treating the comic page as a panel. Another artist who experimented with the comic page was Winsor McCay, the creator of Little Nemo.

There was a lot of formal experimentation in comics in the 60s with underground comix. Artists like Trina Robbins, Robert Crumb, Bill Griffith, Denis Kitchen and Gilbert Shelton all pushed the boundaries of what comics could be. Another underground comix creator Art Spiegelman, with his partner Françoise Mouly, published the anthology RAW which included a serialisation of Maus and broke new ground for comics, preparing the way for a new generation of artists including Chris Ware, Daniel Clowes, Charles Burns and The Hernandez Brothers. All of that fed into the evolution of the graphic novel.

The other tributary for graphic novels is the comic strip. Amazing fully-formed creations like Pogo, Peanuts or Calvin and Hobbes. The worlds are complete and even though it is a weekly strip it’s not such a different art form to creating comic pages or graphic novel pages and the comic strip and even the newspaper cartoon have contributed to the medium and indeed have made people feel like they can read graphic novels, made people feel comic-literate.

Comic masters including Steve Ditko, Jack Kirby, Bernard Krigstein, Basil Wolverton and Harvey Kurtzman, to name only some creators, have also informed the modern graphic novel through their imaginative approach to visual storytelling.

Many people still thought that comics were something for kids, juvenile and intellectual unsatisfactory. In 1986 the media decided that comics had finally grown up, with three books termed the Big Three: Watchmen by Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons, The Dark Knight Returns by Frank Miller and Maus; while both Watchmen and The Dark Knight Returns came from the superhero tradition Maus was very much a product of underground comics.

The shift towards the personal – Maus was the first second-generation Holocaust memoir and approached Art Spiegelman’s relationship with his father as well as documented his father’s survival.

Other personal/political documents followed including Persepolis by Marjane Satrapi – originally published by L’Association in France. In the 90s we saw a proliferation of graphic novels from new, small publishers around the world.

There was a further watershed when Chris Ware’s graphic novel Jimmy Corrigan, the Smartest Kid on Earth won the 2001 Guardian First Book Award, the first time a graphic novel has won a major United Kingdom book award.

Sandra: With technological innovation and an electronic speed of communication the world has been connecting so quickly that influences from much further afield can also be seen. From the worlds of manga and anime: not only in terms of drawing style and visual language but also in terms of story pacing and the almost real-time feel. Great manga artists like Osamu Tezuka and Yoshihiro Tatsumi are definitely an influence on modern comics, as is anime, which has become increasingly popular world-wide too. Studio Ghibli with Hayao Miyazaki and Yoshifumi Kondō, among others, is a good example. Everyone should watch My Neighbor Totoro.

Leslie: What is unique about graphic novels? What can they do in their own right as an art form and add to a story?

Sandra: Each art form is unique and does something that other artforms can’t do, by definition, because they are different media. Graphic novels are an incredibly dynamic art form – they can tell a story in a unique way. They are part prose, part cinema and part painting, and none of these things at the same time.

John: Words and pictures can combine in so many interesting ways – not only as a tautology or emphasis, or as a contrast but they can also create a third space: something wholly new that emerges from the combination of the text and picture. Even after a quarter of a century working with them we both still love comics.

Next week I interview multi-disciplinary, mixed race, scriptwriter and songwriter Charise Sowells.

ABOUT LESLIE TATE’S BOOKS:

I interviewed artist Sarah Ross-Thompson whose exceptional Collagraphed prints use fabrics, lichen, porridge and string to create images of the dramatic Scottish Highlands where she

Part 2 of my interview with Mark Statman looks closely at Mark’s Latin American poetic influences, his life in Mexico and ends with an extract

I interviewed international poet and translator Mark Statman about Volverse/Volver, his 14th published collection. Mark, who has won national arts awards, is Emeritus Professor of Literary

I interviewed Lisa Dart, finalist in the Grolier, Aesthetica and Troubadour Poetry Prizes and author of The Linguistics of Light (poems, Salt, 2008), Fathom (prose

I interviewed writer Julia Lee Barclay-Morton about her experience of autism. Julia began as an experimental dramatist in New York, moving to the UK to

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

2 responses

Great source of information from a couple who have dedicated their adult lives to developing an inspiring level of quality that stands comparison with all the greats they discuss here. Their work inspires countless children-including my own- who relished the glorious imagery and storytelling metaphrog have blessed us with..

🙂 🙂 🙂