SARAH ROSS-THOMPSON AND THE ART OF COLLAGRAPHED PRINTS

I interviewed artist Sarah Ross-Thompson whose exceptional Collagraphed prints use fabrics, lichen, porridge and string to create images of the dramatic Scottish Highlands where she

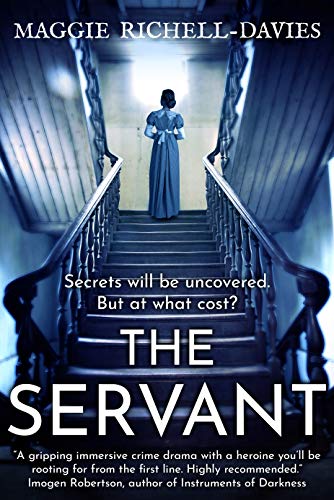

I interviewed author Maggie Richell-Davies about winning the Historical Writers’ Association 2020 Unpublished Novel Award, with The Servant. Maggie says about her book: “It was inspired by a visit to London’s Foundling Hospital Museum, with its heart-breaking stories about the tokens desperate women left there in the hope that they might, one day, be able to reclaim their child.”

I also asked Maggie, who has been shortlisted for the Bridport Flash, Olga Sinclair and Joan Hessayon Awards, about what it’s like to be a first-time published author late in life.

Leslie: Can you explain what you mean by, “…my link with the north-east is reflected in my author name: Maggie Richell-Davies.”

Maggie: I was born in Newcastle during WW2 to a Scottish father – away in Europe with the army – and a Northumbrian mother. It was her love of reading and of history that set me on the road to becoming first a reader and then a writer, which is why – after discovering other authors called Maggie Davies – I linked her family name with my own. I also dedicated The Servant to her: For Florence Richell, who dreamed of teaching but, as a miner’s daughter, had to forego a scholarship and go into service in far-off London.

Leslie: At 78 you have your debut novel published. What have been the key events/influences in your life that led to this book?

Maggie: Working class girls of my era were expected to become secretaries, shop girls or nurses before marrying and having a family. For us, university entry and careers in the professions were unheard of, as was the writing of novels. So my destiny was secretarial college – although I did start writing what today would be called flash fiction, some of which was read out in class for shorthand speed practice.

But after marrying a civil engineer with the United Nations and accompanying him to places like Peru, Africa and the United States, I spent many solitary hours when he took off in a jeep, or on horseback, searching out suitable sites for the building of dams. So I began writing both a diary and short stories. An early effort sent to The New Yorker was, not surprisingly, declined, but I decided that writing was something I was meant to do.

Then, following the end of my marriage and my return to England, I took an Open University degree. It focussed on my two loves, of literature and history, and taught me about research, about structuring an essay and about time-management, since I was also working full time as a PA in central London.

Collecting my first class degree eight long years later gave me the confidence to attempt the seemingly impossible: a novel of my own.

Another milestone was enrolling in a creative writing class. Writing in isolation is hard and asking my second husband what he thought of early drafts put him in an awkward position: might honest criticism land him in the spare room? Fortunately, like-minded people from the class decided during coffee breaks to continue meeting after the course finished. Our self-help group continues to meet to this day, to discuss one-another’s work, and even has its own website. If enough tactful misgivings are voiced about whether your elderly butler would be capable of killing a visiting infantry officer with a butter knife, you know a re-think is needed.

Over time, and success with a handful of short stories, I began experimenting with novels.

Leslie: What’s special about being a septuagenarian novelist? How does getting old count against a first time novelist?

Maggie: People seem astonished that I not only published my debut novel, The Servant, in my seventies but that it also won the Historical Writers’ Association 2020 Unpublished Novel Award – plus a publishing contract. My own surprise is that more writers, especially women, don’t emulate my example since often only in retirement can time be found to fine-tune a hundred thousand words into a publishable book.

Maggie: People seem astonished that I not only published my debut novel, The Servant, in my seventies but that it also won the Historical Writers’ Association 2020 Unpublished Novel Award – plus a publishing contract. My own surprise is that more writers, especially women, don’t emulate my example since often only in retirement can time be found to fine-tune a hundred thousand words into a publishable book.

I have heard it said that agents and publishers are only interested in ingenue writers, perhaps because they clearly have more years – and possibly more books – ahead of them. Yet submissions rarely require you to reveal your age and by the time an agent or publisher falls in love with your book your age becomes secondary. And mature writers not only have less pressures on the hours in their day, with fewer family and work distractions, but tend to be more disciplined. They don’t squander time.

Leslie: Where does your endurance come from? How have you tried to mitigate the ageing process?

Maggie: Genetics probably. Both my mother and maternal grandmother lived into their late nineties, despite having lived hard lives. But both were women with robust senses of humour, who engaged with other people: my mother couldn’t stand at a bus stop without chatting to a stranger. I think that is the answer: being active mentally and physically. My husband and I regularly walk and garden and also belong to that marvellous organisation, the U3A. In ‘normal’ times you can join their reading groups, enjoy museum and theatre visits, or learn about computers, photography or wild flowers. Many continue to meet on Zoom, including my own ‘technology’ group. I can’t recommend the organisation highly enough.

Leslie: How did you set about writing The Servant? What were the key moments and turning points in the research and writing process?

Maggie: Being originally from south London, my husband introduced me to Bloomsbury’s Foundling Museum, a place I hadn’t previously known existed. It is an emotive place, full of heart-wrenching stories about life before the welfare state and with a collection of the coins or scraps of fabric left as ‘tokens’ by mothers in the hope that they might one-day be able to reclaim the babies they were forced to give up because of poverty or the stigma of an unwed pregnancy.

I felt an immediate emotional connection with a scrap of silk embroidered with my own initials. The fabric was fine, the needlework exquisite. This could not have been the work of an illiterate girl from the slums and I wondered: had she been a lady’s maid? A governess? A young society woman who made a calamitous mis-step in love? And was she ever reunited with her child? I couldn’t get it out of my mind and went straight home to craft a story around it.

What I wrote was subsequently entered into a Fish short story competition which offered a critique to all entrants – an invaluable help to writers struggling to find their voice. And although the story failed to be placed, that critique suggested not only that the story needed a much larger canvas – a novel – but that the editor felt me capable of producing one.

It took a couple of years to do the necessary research and evolve my story but, with the encouragement of my husband and my supportive writing group, I began submitting to agents and entering it into competitions.

Leslie: What have you learned about yourself from studying women’s history?

Maggie: Mainly that human nature doesn’t change much. Despite huge differences between myself and the fictional Jane Eyre, I found it easy to identify with her frustration at women’s limited opportunities compared to men. It is a theme explored in The Servant, where several female characters are forced to make compromises in order to survive. I am thinking here of my gin-drinking, pipe-smoking child minder, Fat Nellie, whom several readers have written of admiringly. She is flawed, and you wouldn’t want to leave your child in her care, but she has a good heart.

Leslie: Why do you write?

Maggie: My urge to write grew from being seduced by the ability of authors like Charlotte Bronte and Jane Austen to not only apply a microscope to human behaviour, and be able to transport their readers into different worlds, but to make that journey magical.

Next week I interview multimedia artist, musician and storyteller Cina Aissa, who uses the gifts of neurodivergence and disability to make the world a better place.

ABOUT LESLIE TATE’S BOOKS:

I interviewed artist Sarah Ross-Thompson whose exceptional Collagraphed prints use fabrics, lichen, porridge and string to create images of the dramatic Scottish Highlands where she

Part 2 of my interview with Mark Statman looks closely at Mark’s Latin American poetic influences, his life in Mexico and ends with an extract

I interviewed international poet and translator Mark Statman about Volverse/Volver, his 14th published collection. Mark, who has won national arts awards, is Emeritus Professor of Literary

I interviewed Lisa Dart, finalist in the Grolier, Aesthetica and Troubadour Poetry Prizes and author of The Linguistics of Light (poems, Salt, 2008), Fathom (prose

I interviewed writer Julia Lee Barclay-Morton about her experience of autism. Julia began as an experimental dramatist in New York, moving to the UK to

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

5 responses

Hi Leslie, this is a fascinating piece and Maggie’s story is fascinating and wonderful. I know other female English authors who also struggled against the limitations of the era when it came to writing and publishing.

BTW, my copy of Love’s Register has finally arrived and I look forward to starting it later this week.

This is fabulous! Congratulations, Maggie! I, too, was inspired in part to include a touch of the Foundling Museum’s history in my novel, The London Monster, after a visit to the Foundling Museum. Because of that, I’m especially looking forward to reading The Servant! Wishing you tremendous success with your debut!

Thank you, Donna!

Maggie is such a sweetheart. She is talented and obstinate. An inspiration to everyone that thinks it’s too late to pursue their dreams. I loved The Servant, and I’m looking forward for her next book.

🙂 🙂 🙂