SARAH ROSS-THOMPSON AND THE ART OF COLLAGRAPHED PRINTS

I interviewed artist Sarah Ross-Thompson whose exceptional Collagraphed prints use fabrics, lichen, porridge and string to create images of the dramatic Scottish Highlands where she

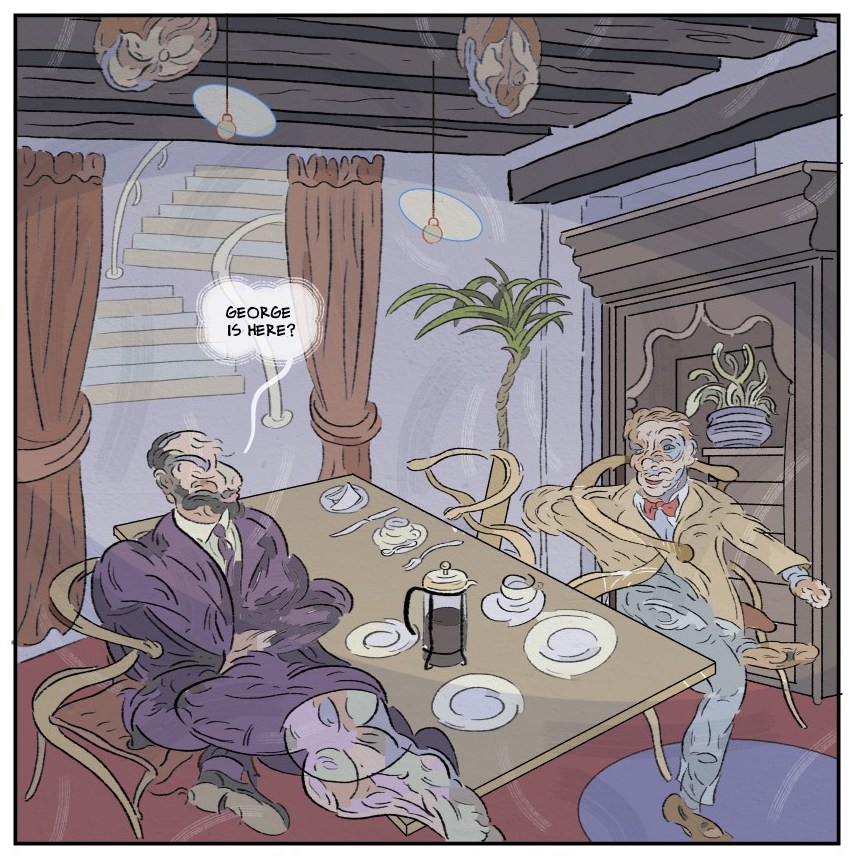

In part two of my interview with graphic novelist Graham Johnstone, we talked about his working methods and how he uses found objects. Graham also describes what went into earlier works of his, including The Curse of the Yellow Book and The Chimera Tree.

Leslie: Tell us about your working methods. How did you develop a visual language for each artist that mirrors its subject but fits to a comic?

Graham: I think I’m quite a versatile artist that can adapt to different styles, and that was much of the initial appeal of working on projects about different artists reflecting their various styles.

I was clear that the Vermeer and Uccello stories required a realistic style. I draw using the Manga Studio/Clip Studio software, and made use of its 3D posable models for the Uccello story. That worked better than the photo reference or posed selfies I used in the Vermeer stories. You’re spot on about pitching the art somewhere between the painted styles of my subjects, and the line-drawings-with-flat-colours tradition of comics. I made the Uccello colour more flat to match his paintings, whereas I added more shadows and fade effects for Vermeer, who has been described as ‘painting with light’.

That realistic style isn’t my forte, and I was glad to leave it behind for the 20th Century artists. My strength is more the expressive and communicative elements of the medium: composition, visual symbolism, sequence and timing, relationships between text and image, body language, expressive rendering, and so on. That said the Picasso and Bacon stories brought their own stylistic challenges. I toned down the Cubist effects for the former, and channelled the simplified figures of his earlier work. For the Bacon book, I began in ‘full Bacon’ style, before toning this down for the start in order to gradually draw the reader into the Baconesque art.

Leslie: Can you explain the cultural and personal importance of the found object and how you adapted the idea to The Curse of the Yellow Book?

Graham: I initially studied fine art so was aware of found objects used in early modern art, for example, Marcel Duchamp’s ‘Fountain’, which was a mass-produced urinal, on its back on a plinth. It was a mischievous and provocative act that questioned ideas of creativity, originality, and the boundaries between ‘high’ and ‘low’ artefacts. As someone caught in the no-man’s-land between supposed high and low forms, those ideas still resonate with me.

Some of my earliest comics used various kinds of ‘found’ texts. One adapted a book and page ‘randomly’ selected from my shelves: Albert Camus’ novel The Outsider, (called The Stranger in America). Another matched a ‘found’ essay about realism in painting, with a single ‘found’ object (a shoe) rendered in ways that reflected the supposed elements of realism, like conveying ‘tangibility’, and ‘drawing from observation’.

The Curse of the Yellow Book uses the literary device of the ‘found fiction’. That is to say, the author fictionally claims to have found a text they actually wrote. My book is presented as the unpublished memoir of my namesake, a century earlier, a device intended to distance the reader and have them doubt the reliability of the account. I used other ‘found’ sources in the story: my title references ‘notorious literary periodical’ The Yellow Book, the ‘curse’ element mirrors another period text The King in Yellow, and I incorporate elements of ‘found’ images related to the literary sources.

Leslie: What was original/distinctive about your early work around trees? What was its developmental importance for your work?

Graham: The early work around trees partly happened through chance. I was invited to submit to an exhibition linked with a Garden Festival that seemed to represent a process of regeneration I was at best ambivalent about. That’s captured in ‘The Cuckoo Plant’ – which is named for an invasive presence, like cuckoo eggs laid in another bird’s nest. However, I realised that drawing everyone as plant creatures avoided the everyday banalities of costumes and settings that would limit the stories to a particular time and place – which I also had no interest in drawing. Instead I got to draw the more dynamic and expressive elements of trees growing and dying. I didn’t go back to naturalistic imagery until it was necessary for the more historic artists.

Leslie: Who are the top three artists you admire? What have you learned from them and what do you incorporate into your own artistic practice (perhaps hidden)?

Graham: I’ve already discussed the painters I’ve done stories about, so I’ll focus on comics and graphic novel creators. One of the first comics artists to grab my attention was Steve Ditko, who drew for Marvel in the 1960s. He used the arrangement of panels on a page, and figures within those panels to make a series of still images that create the experience of motion. That, and the careful placement of word balloons and captions within the images convinced me that comics were a unique medium, and quite distinct from film – they assert their identity as multiple images on a page. In my own work, that’s most obvious in ‘Recalling the Chimera Tree’, where the panels on each page form a rough composite image of a tree, with a central trunk, and branches off. In my current project about Francis Bacon, my pages are all variants on three rows and three columns of panels to reflect his preferred triptych form. You couldn’t have that in film.

At the end of my teens, I discovered Art Spiegelman’s book Breakdowns. He’s more famous for Maus his Pulitzer winning memoir about his parents’ experiences as Jews in WWII, but this was a collection of short, formally experimental comics. The main lesson I learnt from him was the repetition and variation of images. The influence is most obvious in the minimal, systematic imagery of Tangled Tales. Any time I can repeat an image with a variation to highlight a change or convey a new a meaning, I’ll usually do it. That might seem an easy short-cut, but often it involves cutting a drawing I’ve already done. It’s a way of reducing white noise – extraneous information or unintended meanings. I also learnt from Spiegelman that keeping all the panels the same size makes it easier to repeat images in that way.

So having absorbed that formal playfulness, the next influence was the UK small press comics boom of the 1980s and 90s centred on the Fast Fiction zine, and distribution service. It was a small circulation zine but published some highly accomplished and original work. It was the comics equivalent of that joke about The Velvet Underground – few people bought their records, but they all formed bands. The main lessons I took from Fast Fiction was that one could put personal experience into comics, in oblique and poetic ways. The existence of a scene and sympathetic audience, however niche, prompted me to start art comics anthology Dead Trees, and produce my first sustained body of work.

Leslie: Looking back, what personal qualities, educational experiences, mentoring & lucky breaks have helped you to become a graphic novelist?

Graham: For education, I went to Glasgow School of Art at eighteen. I imagined I would become an illustrator, (in comics or otherwise). However, over the first year general course, I released I was doomed to be a fine artist – pursuing my own interests, rather than realising the vision of writers, editors or clients). So I opted for fine art, where I did mostly printmaking. That fine art sensibility still drives me – like Francis Bacon, I’m trying to do something more than literal illustration of ‘fact’.

I soon realised that to make a living I’d have to either do a different kind of art, or find a totally different career. I found an alternative vocation in community development, as a practitioner, manager, and leader. While that took time away from my creative work, it gave me useful qualities like focus and endurance, to pursue projects over a long period, and the urge to make sure my ideas connect with others. I gained an empathy and insight into people, without which I can’t imagine being able to do justice to, say, the tragic love story of the Francis Bacon book.

I did eventually reach the point I needed more time to actually make the work, and was able to leave my job. Since then I’ve done a Master of Design In Graphic Novels, and three years of part time fiction writing studies. I appreciate having accessed all that education. After decades as a qualified artist, I’m still learning and facing new creative challenges every day. All of that has helped me keep getting better, and now I’m concentrating on applying it all to the Francis Bacon book.

I’ve been fortunate in accessing all these learning opportunities, and I realise that’s an unusual route no else is going to replicate. I suppose the transferable lesson is to draw on whatever you can. I think I’ve been shaped by living in Glasgow, a city with strong creative cultures and communities. There is a culture (in the broader sense) that’s both supportive and challenging. I’ve really benefited from sharing my work and getting feedback, most recently in writers’ groups. Learning about theories and methods is great, but there’s no substitute for thoughtful people looking at your work and telling you where it doesn’t make sense. No one’s ever told me my work’s too left-field (though they may have thought it), or to go and do something different, but they’ve given me specific feedback and helped me find solutions. That’s something anyone should be able to access, and probably the best way to keep improving in any creative field.

It’s a pretty unique route I’ve taken, and hopefully I am now better able to channel that into work that’s original, artful, and accessible.

Thanks for including me in your interview series Leslie, and for your very astute, though hard to answer, questions.

The opening pages of the Francis Bacon graphic novel are most easily read on Pinterest. Tangled Tales is available to buy on Apple’s iBooks: search for ‘Graham Johnstone’ on the in-app store.

Next week I interview Sue Hampton about her latest book Still Rebelling for Life. Sue describes herself as: “Quaker, climate & peace activist, grandma, author of 40 titles for kids, teens & adults. BLM, Campaign Against the Arms Trade (CAAT), refugees are welcome. Love wins.”

ABOUT LESLIE TATE’S BOOKS:

I interviewed artist Sarah Ross-Thompson whose exceptional Collagraphed prints use fabrics, lichen, porridge and string to create images of the dramatic Scottish Highlands where she

Part 2 of my interview with Mark Statman looks closely at Mark’s Latin American poetic influences, his life in Mexico and ends with an extract

I interviewed international poet and translator Mark Statman about Volverse/Volver, his 14th published collection. Mark, who has won national arts awards, is Emeritus Professor of Literary

I interviewed Lisa Dart, finalist in the Grolier, Aesthetica and Troubadour Poetry Prizes and author of The Linguistics of Light (poems, Salt, 2008), Fathom (prose

I interviewed writer Julia Lee Barclay-Morton about her experience of autism. Julia began as an experimental dramatist in New York, moving to the UK to

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |