Part 2 MARK STATMAN: MEXICO AND THE POETRY OF GRIEF AND CELEBRATION

Part 2 of my interview with Mark Statman looks closely at Mark’s Latin American poetic influences, his life in Mexico and ends with an extract

I interviewed Ian McLachlan, co-founder of Poets For The Planet and environmental campaigner. Ian describes organising and appearing in major poetry events such as Earthsong at COP26, Verse Aid and Begin Afresh as well as his creative collaborations and community performances.

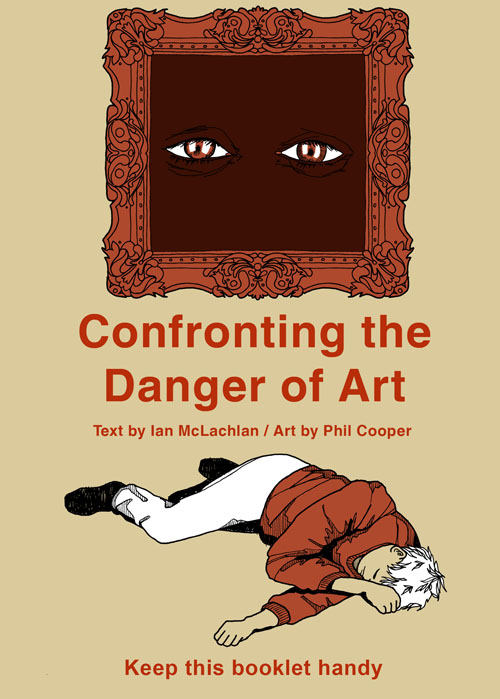

Ian‘s poems have appeared in Magma, Poetry Salzburg Review, and The Rialto, and his illustrated poetry pamphlet Confronting the Danger of Art was a joint collaboration with the artist Phil Cooper.

Leslie: Tell us about Necropolis, how you wrote it, put it together, and what someone might encounter if they read it.

Ian: Necropolis is a collection of 15 London-based poems I put together in 2008 for the Mimesis Digital Chapbook initiative.

At that time I wrote a lot of semi-autobiographical poems about the grind and glamour of obscure creative lives lived in a forceful and indifferent city. These 15 poems were the ones I liked best, or that had received the best feedback on websites like ABCtales and DeviantArt where I used to post regularly. The landscape of the collection is house-shares, laundrettes, gyms, open mic nights. Under the surface, there’s a yearning to transcend the mundane, and a rejection of socially conformist and hedonistic lifestyles.

Leslie: You produced, hosted and performed at Earthsong. Tell us what it is, how you began, grew and developed it and the impact it had on you and its audiences. What made you an environmentalist and where does the drive to organise Earthsong come from?

Ian: Earthsong was an ecopoetry show consisting of 19 poets from five continents performing live or on film in 12 different languages. The show was a collaboration between Poets for the Planet and Imperial College London, and it ran at the Great Exhibition Road Festival in South Kensington, and at COP26, the United Nations’ Climate Change Conference in Glasgow.

Earthsong started its life when Poets for the Planet put in a bid for a performance slot at COP26. Our Poets for the Planet working group selected writers from around the world and invited them to attend online workshops with environmental scientists to create science-informed poems. The participants then made filmed versions of their poems which we subtitled in original language and English. Depending on availability, they either performed their poem live at the Great Exhibition Road Festival and COP26, or we screened their filmed poem.

Audience responses were very supportive and included: ‘Really impressive and very moving panorama of languages and cultures’ and ‘Give it a listen, it will change you’.

I was proud to have helped put the show together but it was an awful lot of work over a short timeframe – we were only notified our COP26 bid had been successful two and a half months before the event. Adding subtitles in original language and English to filmed performances delivered in languages we didn’t speak was particularly challenging – lucky Google Translate exists! And I’d have liked to have had more time and resource to promote COP26 and our involvement in it online, given that our show consisted of digital assets optimised for social media. Overall, it was a very demanding but very positive experience for me.

Regarding my environmentalism, I’ve always been troubled by the way we treat the planet and for many years have tried to mitigate my own negative impact, for example, by not eating meat and predominantly travelling on foot or by public transport. But over the last few years the scale of the environmental crisis and the apparent incapacity of governments to deal with it has pushed me towards activism. I attended my first Extinction Rebellion protest in December 2018. Then in May 2019 I helped found Poets for the Planet, and I also started attending meetings of Extinction Rebellion Hackney. It seems natural to put my craft as a writer at the service of the planet, and I also advocate for environmental action in my ‘day-job’ at a London university, heedful of Arthur Rimbaud’s maxim: ‘Enter everywhere’.

Leslie: You produced Confronting the Danger of Art with Phil Cooper. What’s the tone and intention of this book, where did the idea come from, and how did you work together on it?

Ian: I was very grateful to Kirsten Irving and Jon Stone from Sidekick Books for bringing Phil Cooper and me together and inviting us to create an illustrated poetry pamphlet. I put a number of ideas to Phil, including one about a world in which art had been banned, inspired by Plato’s anti-art arguments in Book X of The Republic. Phil liked the idea and suggested the pamphlet’s look imitate public information booklets produced in the 1970s/80s like the government nuclear war response Protect and Survive.

We worked on the project entirely online, with me sending Phil drafts of the poems which he then illustrated. The tone of the pamphlet is satirical with Phil’s artwork adding a whole new dimension of bizarreness and humour. One of the functions of the pamphlet is to highlight the ways in which authorities/the media single out minority groups for negative treatment and the absurd attributes they apply to them to justify and encourage negative treatment.

I used to busk the pamphlet outside Tate Modern on the South Bank and was always intrigued by people who failed to appreciate its satirical nature. I remember one woman telling me I was a very dangerous man and that if the police found out what I was doing they’d shut me down.

Leslie: Why did you choose Catullus’ poem 51 to film?

Ian: I wrote a film noir version of Catullus 51 for Sidekick Books’ anthology Bad Kid Catullus which was released in 2017, and which The Guardian listed as one of the top ten poetry anthologies of 2018. Then in 2021 Kirsten Irving asked me to contribute a film of that poem as part of Sidekick Books’ showcase at Jake Wild Hall’s online OOIPP festival. I read classics at university and I’m interested in creative work that is strange and morally ambivalent, so I really enjoyed writing and filming this poem.

Leslie: You have co-organised and run several other eco-poetry events. Can you tell us stories about the most interesting, challenging and successful, please?

Ian: After Earthsong, the most challenging event was probably Verse Aid, Poets for the Planet’s launch at the Society of Authors, because it involved three different elements: a 40-poet Poem-a-Thon, 14 eco-themed poetry workshops, and an evening gala headlined by Imtiaz Dharker. Attendance was good throughout the day and we raised around £6,800 for environmental charities Bees for Development and Earthwatch. Though I circulated a press release very widely, the event didn’t attract much media attention, but I think it helped increase awareness of the climate crisis among the UK poetry community and those friends and family who sponsored the Poem-a-Thon.

A month after Verse Aid we were hit by the pandemic, so the new lockdown restrictions challenged our capacity to reach audiences very early in the life of Poets for the Planet. We responded by running a digital campaign on Twitter called Begin Afresh. The title came from the last stanza of Philip Larkin’s poem The Trees, and the campaign was inspired by the idea that the greater appreciation of clean air and greenery felt during lockdown might encourage society to focus much more strongly on nature and on tackling the climate, biodiversity, pollution, and overconsumption crises. Poets were invited to upload filmed ecopoems to Twitter along with the hashtag #BeginAfresh. We opened the campaign with contributions from Poets for the Planet’s patrons, poet laureate Simon Armitage and the poet and The Verb presenter Ian McMillan. More than 30 poets contributed, with each poem receiving around 100 – 2,500 views, and the campaign earning 84.9k impressions in its first month.

A thermally imaged Simon Armitage speaks to us from the near future with his poem Last Snowman (from The Unaccompanied, @FaberBooks, 2017). #BeginAfresh https://t.co/3rexDpR5kC pic.twitter.com/m1L0zBYmK1

— Poets for the Planet (@poets4theplanet) June 9, 2020

Leslie: You’re also an actor and performer. Tell us stories about some of the standout moments from your career as a community poet and performer.

Ian: I’ve taken acting classes, sang in the West End production of Evita as a child, and most recently co-produced and performed a version of the Brothers Grimms’ Bremen Town Musicians for an event at Wembley Park, but I don’t think I could describe myself as an actor as I’ve only ever done occasional acting-related work.

Some of my favourite moments as a poet include performing on the pink boat for Extinction Rebellion’s North London Uprising Festival and reading alongside four singer-songwriters for a COP26-themed event at Galoshans Festival in Scotland. The latter performance was filmed without audience at The Albany Theatre in Greenock and it was quite a strange experience to recite to a hall that was empty but for the stage and camera crew.

Leslie: How does your love of skateboarding and guitar relate to your activities as a poet?

Ian: I don’t really have time to skateboard now but I used to like bowl-riding in particular because of the sense of freedom it gives, of almost becoming pure movement as the board seems to dissolve under you. And I like the counter-cultural element of skateboarding that it inherited from surfing – the rejection of consumerism and mainstream society. The desire for freedom and the rejection of social conformity are strong themes in my poetry. Similarly, the guitar for me is a symbol of freedom, of travelling light and refusing those social forces that seek to ossify your life. Ditto poetry. They’re acts of opposition against a society that prioritises getting and spending over thinking and being.

Next week I interview Liza Adamczewski, painter, printer, creator of postcards, ceramics and golden triptychs.

ABOUT LESLIE TATE’S BOOKS:

Part 2 of my interview with Mark Statman looks closely at Mark’s Latin American poetic influences, his life in Mexico and ends with an extract

I interviewed international poet and translator Mark Statman about Volverse/Volver, his 14th published collection. Mark, who has won national arts awards, is Emeritus Professor of Literary

I interviewed Lisa Dart, finalist in the Grolier, Aesthetica and Troubadour Poetry Prizes and author of The Linguistics of Light (poems, Salt, 2008), Fathom (prose

I interviewed writer Julia Lee Barclay-Morton about her experience of autism. Julia began as an experimental dramatist in New York, moving to the UK to

I interviewed Gillean McDougall from Glasgow, who edited the collaborative projects Honest Error (on Charles Rennie Mackintosh and his wife Margaret Macdonald) and Writing the

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |