Part 2 MARK STATMAN: MEXICO AND THE POETRY OF GRIEF AND CELEBRATION

Part 2 of my interview with Mark Statman looks closely at Mark’s Latin American poetic influences, his life in Mexico and ends with an extract

I interviewed Hannah Linden, winner of the Café Writers Poetry Competition and shortlisted for the Saboteur Awards. Hannah says about her powerful poetry pamphlet The Beautiful Open Sky, that it explores “the territory of being the child of a very young mother and then the knock-on effects this has on my own experiences as a mother.”

Leslie: What aspects of your pamphlet ‘The Beautiful Open Sky’ are literal and drawn from life? What parts are generic or metaphorical? How did you deal with the moral issues of representing your family both truthfully and how they’d like to represented?

Hannah: Obviously, I am exploring the territory of being the child of a very young mother and then the knock-on effects this has on my own experiences as a mother, but most of the poems in the pamphlet are extended metaphors so they are not meant to be read as ‘literal’ in a straightforward sense. I was not led into the forest like Hansel and Gretal, for example (as in my poem The Cottage in the Wood).

Many of the poems started life from a very different initial starting point but there are lines that are drawn from real life in there: fragments of conversations, memories of particular objects or events, for example, but they are placed into a symbolic context which enables an exploration of an emotional truth rather than a literal one. That truth may have only become available much later (sometimes only when the poem has revealed it to me) and, if it was limited to only my individual truth, I think the poems would be less useful to other people. Any poem is an interaction between poet and reader and I intend to leave a lot of connotational spaces for different readers to interpret the meanings in their own way.

In terms of the moral issues of representing my family, I think there is a distinct difference, ethically, in regards to my responsibility as a child and for me as a parent. The poems that explore the experiences of my children were given their direct blessing before they were ever shown to anyone outside the family.

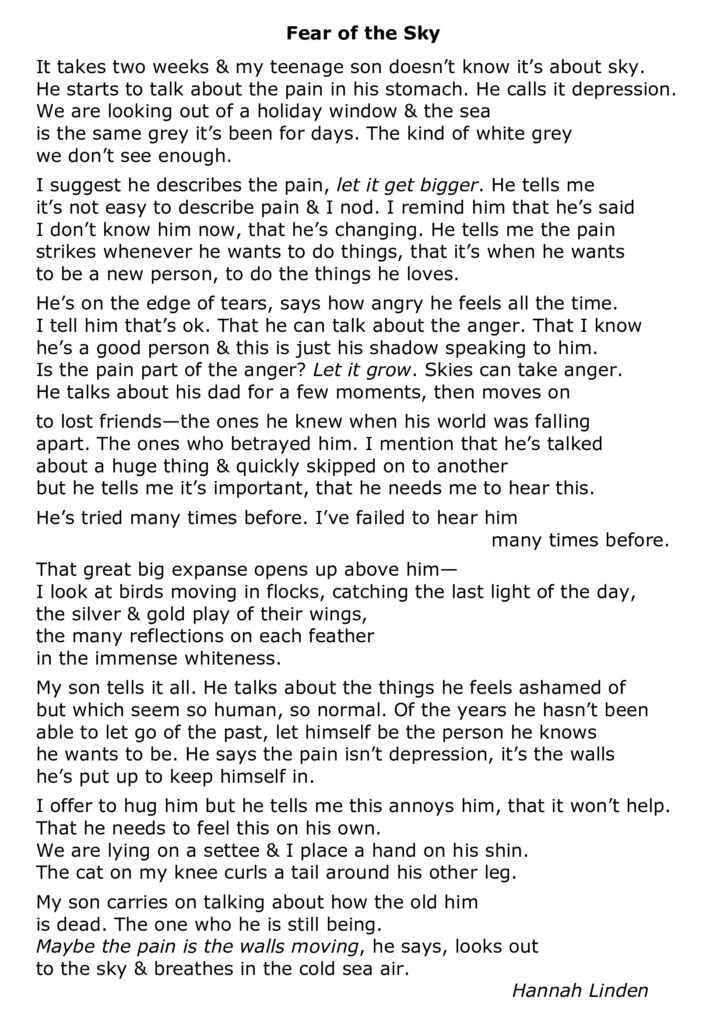

Some of those were written as a way of me trying to understand them and only for that reason. Fear of the Sky, for example, was very much not intended to be published when I wrote the initial draft. My son, however, after pondering on it after I shared it with him to check I’d heard him properly in a private conversation, thought (as the conversation moved further into the past) that I ought to publish it because he felt that people should have an insight into how teenagers experience the world, especially in terms of how they process difficult experiences. He helped me to edit it so that it would be as true as possible and so I changed a ‘tidier’ ending into a more open-ended one. He, also, accepted the ways in which I’d abridged or extended certain parts of the ‘literal’ framework of a very long and in-depth conversation in order to get to the essential parts of the experience.

Another poem about my son’s interactions with me, The Stars That Are Cherry Stones That Have Lost Their Colour, was a poem that brought together many different conversations or starting points too and was a useful poem for explaining to my son, when he was younger, how a poem works in the liminal spaces between literal and meta-truth-telling.

My daughter is also a writer and is very committed to us both being able to write freely. She very much supports my poetry and thinks it’s important but she requested that I don’t read some of them in public if she is there. This is not because she doesn’t think they are true and respectful but because they take her back to a difficult time in her life and she doesn’t want to go back there in public. Again, it’s the emotional truth of a poem that would have a particular connotation for her that she’s thinking about, rather than a literal memory.

As regards to the poems that explore childhood experiences of one’s own, I think that no one should have to seek permission from a parent. It is your own experience and so that belongs to you. I don’t read my daughter’s writing so that she can feel free to write whatever she feels is her experience, taste and interpretation. To limit that seems, to me, to be deeply oppressive and, especially when one’s childhood has been traumatic in any way, it is particularly important to be able to process things that need to be expressed, either as a healing journey for oneself (and hopefully for others who read it) or as a howl. The poems that explore my relationship with my mother are very metaphorical and so the ‘truth’ is an emotional landscape rather than a detailed autobiography of factual events. Whereas I do have a duty of care for my children, I don’t feel that same duty towards someone who was an adult when I was a child. I think that silence about difficult childhood experience is not healthy for oneself or for wider society. It was important, to me, to include poems that show that the role of Mummy, Mum and Mother are not straightforwardly good or bad; her or me. So, in The Shed, for example, I’ve given voice to how I imagined my children could write about how they navigate living with a mother who suffers from depression and anxiety. And the ‘Good Mother’, in one of the later poems, is a ‘she’ rather than an ‘I’.

Leslie: Is writing about a difficult childhood therapeutic, confessional and/or very challenging? How do you achieve distance while remaining emotionally connected when writing this way?

Hannah: I’m always a little confused by this way of framing things. When someone explores an ‘easier’ childhood, is that also ‘therapeutic, confessional and/or very challenging’? I think it can be. I don’t think the difficulty of a childhood necessarily makes writing truthfully, or movingly, any more or less challenging.

The word ‘confessional’ implies that one is seeking some kind of absolution or forgiveness and I certainly don’t think I’m trying to achieve that in a poem. Although I can ‘realise’ for the first time, or anew, certain things that come up in a poem, I think therapeutic work is something that would come after a poem has prompted it, or reflect therapeutic work that has already taken place.

I think a poem can be a signpost to a destination or a direction you need to take (or a marker for where you’ve been) and I think that readers can recognise those signposts in their own journeys. What can feel a lonely, dangerous path is, at least, one that we can share with an empathetic poet whose poem resonates with our experience. I know I’ve felt that solace from poems I’ve read myself and they’ve given me courage.

In terms of achieving distance, whatever my subject matter is, I tend to write, when it’s going well, in a kind of trance state. However, it feels important that I allow myself to be interrupted whilst I’m writing. I can be in the middle of writing a line and go online to look up the secondary meanings of a word; or answer an email or message; or get up and make a cup of tea; or have a conversation. I’ve learnt that this acceptance allows me to pace myself, emotionally and intellectually.

When I return to the poem, the next words are there, waiting. I often don’t ‘feel’ the poem until I read it back later, sometimes much later. This is true whether or not the subject matter is traumatic or perfectly pleasant. It’s often by writing a poem that I learn how I feel about something. The connections, emotionally, are in my back brain (as I call it) and the experience ‘comes through’ me whilst I’m very still, unhindered by a pressure to write well, truthfully or powerfully. If I ‘try’ to write about difficult experiences, at a distance or otherwise, I always fail. It’s much more a process of being surprised by what comes up in the moment. My job is just to turn up and write whatever happens to come to me. I rarely know anything at all about a poem until I’m sitting down to write and the first words appear. Often, I don’t know what the poem is, until it’s nearly finished.

It’s when I come to the editing that it is more tricky, not just because then I know what I’m dealing with but, also, because I don’t want to pretty it up so much that the rawness is diluted or corrupted. Having an editor who was forensic in her methodology was particularly helpful in this regard, though, because she was focusing on making sure I did intend each decision and shining a light on unhelpful repetitions or distractions. That pressure to be precise helped me to push through emotional discomfort and remain rational, which helped a great deal.

Next week, in Part Two, Hannah Linden answers questions about her compositional process, and what she has learned about herself from being a poet.

ABOUT LESLIE TATE’S BOOKS:

Part 2 of my interview with Mark Statman looks closely at Mark’s Latin American poetic influences, his life in Mexico and ends with an extract

I interviewed international poet and translator Mark Statman about Volverse/Volver, his 14th published collection. Mark, who has won national arts awards, is Emeritus Professor of Literary

I interviewed Lisa Dart, finalist in the Grolier, Aesthetica and Troubadour Poetry Prizes and author of The Linguistics of Light (poems, Salt, 2008), Fathom (prose

I interviewed writer Julia Lee Barclay-Morton about her experience of autism. Julia began as an experimental dramatist in New York, moving to the UK to

I interviewed Gillean McDougall from Glasgow, who edited the collaborative projects Honest Error (on Charles Rennie Mackintosh and his wife Margaret Macdonald) and Writing the

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |