SARAH ROSS-THOMPSON AND THE ART OF COLLAGRAPHED PRINTS

I interviewed artist Sarah Ross-Thompson whose exceptional Collagraphed prints use fabrics, lichen, porridge and string to create images of the dramatic Scottish Highlands where she

I interviewed Natalia Millman about her artistic response to dementia, personal loss and grief. Natalia is an intuitive artist who uses found materials to express ‘anticipatory grief’ about dementia and family loss. She regularly uses installation, video, sound, performance and workshops in her work – as in her upcoming St Albans show. Natalia has also developed community art about The Nature of Memories and art to represent the suffering of her homeland, Ukraine.

Leslie: What’s the personal story behind your ‘Vanishing Point’ exhibition at The Crypt Gallery, London? What were the main artworks that appeared in the exhibition? How did creating it affect you?

Natalia: This exhibition grew organically over the course of a year following the loss of my father. Prior to that, I had never experienced grief so intensely. When he died, my world turned upside down, and I found myself unable to paint the landscapes I used to create. Grief left me feeling suspended in a vacuum, observing my life from above as if it were not truly happening to me. I spent a great deal of time outdoors in nature, which had always been a source of comfort and calm. During this time, we were in the process of rebuilding our house, and the space was filled with bricks, broken pipes, tiles, and other debris.

I began collecting broken objects I found during my walks and in the skip. These objects were brought back to my studio and reassembled. Only now do I realise what was happening: this was my subconscious way of repairing, healing, and finding meaning. As the collection of objects grew, my mentor suggested creating a solo exhibition as a tribute to my father, a reflection of my grief process, and a way to raise awareness about dementia, the disease that had affected my father’s mind.

At that point, I reached out to the charity Arts for Dementia, which organises creative activities for people living with dementia and their companions. They were enthusiastic about supporting my exhibition. The parallel between the broken objects I displayed and the effects of dementia became apparent: dementia fractures memories and perception, and loss similarly fragments our sense of identity. Who we once were, we no longer are.

The Oxford English Dictionary defines a “vanishing point” as the moment at which something that has been gradually diminishing disappears altogether. This definition resonated deeply with me, as it reflects the experience of dementia. Those living with the disease may be physically present, but they are no longer fully there; their meanings, perceptions, and memories become muddled and slowly vanish. For those of us observing this process, we experience anticipatory grief—time and space become distorted. We live in the present moment with them, even as we anticipate the reality of their eventual absence.

During that year, I was drawn to tactile materials, finding that touch became a key way for me to process my emotions. The artworks exhibited included paintings and collages of fragmented body parts, a blackened brain occupied by tau proteins, a willow tree juxtaposed with a hospital drip, a brick surface covered in pills, silk-printed photographs, and a video capturing my mother’s body.

Because my father was no longer with us, I collaborated with my mother to document the fragility of both body and mind. This process helped us connect more deeply through our shared grief, transforming our relationship and shifting our roles. I was no longer just her daughter—I was becoming her carer.

Leslie: Can you tell someone unfamiliar with your artwork what they might see/experience in terms of your found materials? How do you choose and modify them, and how and why did you use them in Vanishing Point?

Natalia: The objects I find include both organic materials, such as branches, moss, and stones, as well as non-organic items like broken building materials, pipes, chairs, and fabric. They are selected intuitively, likely based on their shape or texture. Once collected, they are left in my studio for a time, allowing me to observe them. Sometimes ideas emerge immediately, while at other times, they develop slowly, requiring observation and patience. Arranging these materials brings me great joy—much like playing with Lego, which I love. Combining organic and non-organic elements, juxtaposing soft fabric with hard brick, wrapping a spade in medical prescription paper, or placing soil in a glass container—these experiments offer endless possibilities. A piece works for me when it expresses something I feel internally but struggle to articulate verbally. Through this process, my emotions emerge somatically and take shape in the materials I use.

I am drawn to broken objects because, in grief, life itself feels fragmented, and with dementia, identity becomes fractured. This brokenness underscores the fragility of human experience, and these objects help me convey that idea. Nothing is permanent or stable; fragmentation is inevitable, and life is not static. In the process of living, how we approach the parts of ourselves that feel broken and how we reassemble them to create new meanings is central to my work. This leads me to create art that is intentionally non-permanent.

I enjoy using discarded objects that once belonged to others because they carry a history. Incorporating these objects into my work enriches their meaning and function by merging their past with my present.

One of my favorite finds is an abandoned mattress. To me, a mattress symbolises nurture, care, and memory. It once belonged to someone, held someone through the night, and now it has been discarded. I write thought-provoking messages on these mattresses, imagining the messages as if written from the mattress’s perspective. It fascinates me to observe who notices these messages and when the mattress eventually disappears.

Leslie: What aspects of early-stage dementia are echoed in your work? How are they approached/represented?

Natalia: I explore not only the early stages of dementia but also the changes my dad experienced throughout the process of deterioration, as well as what we as a family witnessed. My black ink drawings feature tangles and burn holes in paper, symbolising the broken connections among neurons in the brain. Initially, these disruptions affect areas involved in memory, but over time, they extend to regions responsible for language, reasoning, and social behavior. My work incorporates a lot of blackness, blurriness, ash, tangled string, and wire to represent this inner confusion.

I used my dad’s jumper to wrap around flexible piping, adding grey hair to it as a representation of the ageing mind and a personal connection to my dad. I tear paper, burn it, and reassemble it, emphasising the fragmentation of both mind and body. Hair and hands feature prominently in my work as carriers of origin and ancestral memory.

My dad left a few sketches of his own, though they were very unfinished due to his near blindness and inability to speak. These simple lines on paper are incredibly precious to me. I am currently working on a new series in which I build upon his lines, adding my own and introducing color. This process allows me to bring my dad into my work and respond to his marks, creating a dialogue between us that transcends his absence. It has been invaluable in helping me navigate my grief and maintain a sense of connection with him.

Leslie: Tell us the about the expected engagement with public/volunteers, the planned therapeutic work and what the partner organisations are going to bring to ‘Letters to Forever’ at St Peter’s Church, St Albans.

Natalia: I was thrilled to receive the Arts Council grant this year for my project, “Letters to Forever,” which I have been developing since 2021, following the conclusion of my solo exhibition “Vanishing Point.” This project is based on over 200 grief letters that I have collected and my intuitive artistic responses to them through drawing. The installation, which will include all my research as well as video, sound, scent, and sculpture, will be exhibited in August 2025 at St. Peter’s Church St Albans.

In addition to the visual show, I wanted to create a holistic experience by incorporating practical workshops and engagement activities. These will allow the audience to connect with the project on both a physical and emotional level. I am collaborating with Cruse Bereavement to train workshop facilitators and oversee the activities. They will also be raising funds for their charitable work during the event, and I plan to produce prints of my artwork to contribute to their fundraising efforts.

With Memory Support Hertfordshire, I am designing a workshop specifically for companions of people living with dementia, as their needs are often overlooked. Volunteers invigilating the exhibition will have the opportunity to engage with the public and foster meaningful conversations around grief and healing.

The workshops will include activities such as mindful clay sculpting, yoga, breathing exercises, and journaling for grief, all aimed at helping participants develop coping mechanisms for navigating their grief journeys while connecting with others.

As part of the project, the public will be invited to use art supplies to create their own visual representation of grief on a shared canvas. This communal activity will foster empathy and a sense of togetherness, culminating in a collaborative artwork that reflects shared experiences of loss and healing.

Leslie: In practical terms, can you give examples, please, of how you worked with your own mother. Can you chart how the joint work affected your feelings?

Natalia: I titled our collaborative work “Together After” to reflect our bond and how it transformed after the loss of my dad and, for her, her husband. They were incredibly close, and she struggled to adjust to her new reality. She had cared for him until the very end while I was miles away, managing the logistics from afar. The shock of his loss was immense.

She came to visit me, but soon after, the war in Ukraine broke out, and she never left. Overwhelmed by both her personal loss and the loss of peace in her homeland, she fell into depression. To help her find a sense of purpose, I encouraged her to participate in my art. Together, we embarked on a series of projects that became deeply meaningful for both of us.

We took photos together, intertwining our hands every day for 100 days. We also created two short films. In the first, we observed each other’s faces intently, taking in every detail—every wrinkle and every contour—really being present in the moment and appreciating each other as we are at this stage in our lives. It was deeply emotional. She reflected on me as a child, now grown into a woman, while I thought about how quickly time passes, how she is ageing, and how unprepared I feel for what lies ahead.

The second film explored our swapped roles: I now care for her, whereas she once cared for me as I grew up. We also collaborated on a painting, working side by side to create a single image. This shared experience was incredibly special and became a precious legacy for both of us.

This collaborative work has strengthened our bond, making us kinder and more patient with each other. It has given me a deeper understanding of her ageing process and the passage of time, which feels both joyful and terrifying.

Leslie: Can you give us examples of the words used on the sign board in your ‘Nature of Memories’ project? What feedback have you received about the board’s words, positioning and effects?

Natalia: Like much of my work, this was an intuitive project. I noticed an abandoned sign near my house and approached the local council for permission to use it for my prompts. The location was perfect, as many cars and pedestrians passed by daily. I wanted to connect with the local community by sharing prompts related to nature and memory—short reflections they could read and carry with them throughout their day.

I update the text every 2–3 weeks, offering questions and prompts such as:

Once, while I was writing a new prompt, a police car stopped nearby, and I felt a wave of panic. To my surprise, the officers encouraged me to keep going, saying they always looked forward to reading the new messages when they drove by!

The project was also featured in the local newsletter, and I regularly receive comments on the local social media group from passersby who appreciate the prompts. It has been a rewarding way to engage with the community and spark moments of reflection in their everyday lives.

Leslie: What do your Ukraine artworks look like? Tell us about the materials, figuration, patterns, techniques you use – and why you chose them as your methods.

Natalia: I left Ukraine in my twenties, but my connection to my culture and history has always remained strong. It has been important for my children to learn my native language, not only to communicate with my family but also to understand where their roots lie. We regularly visited my hometown during the summers to experience life from a different perspective.

Since the start of the war, however, my roots have begun to tremble. I felt an overwhelming anger about everything happening. My pieces about Ukraine are infused with red—the color of the blood of all the innocent lives lost. As with all my work, these pieces are highly textured.

One painting features a fragmented body, symbolising a country broken apart yet desperately trying to hold itself together. The canvas is a deep maroon red.

Another piece, “Winter of 2022,” was created at the very start of the war. I filled a clear cube box with artificial snow—reminiscent of Ukraine’s cold winters—stained with artificial blood to evoke a landscape of snow painted with the blood of those who have fallen.

In another work, I used vintage Ukrainian currency as my canvas, painting a tree landscape over it in artificial blood. This piece explores the monetary cost of war, as well as the destruction of history, culture, and nature.

As with some much of my process, I sometimes work with pre-existing objects, manipulating and reinterpreting them to give them new meaning. This approach helps me confront the devastation while preserving a connection to the past and to my homeland.

ABOUT LESLIE TATE’S BOOKS:

I interviewed artist Sarah Ross-Thompson whose exceptional Collagraphed prints use fabrics, lichen, porridge and string to create images of the dramatic Scottish Highlands where she

Part 2 of my interview with Mark Statman looks closely at Mark’s Latin American poetic influences, his life in Mexico and ends with an extract

I interviewed international poet and translator Mark Statman about Volverse/Volver, his 14th published collection. Mark, who has won national arts awards, is Emeritus Professor of Literary

I interviewed Lisa Dart, finalist in the Grolier, Aesthetica and Troubadour Poetry Prizes and author of The Linguistics of Light (poems, Salt, 2008), Fathom (prose

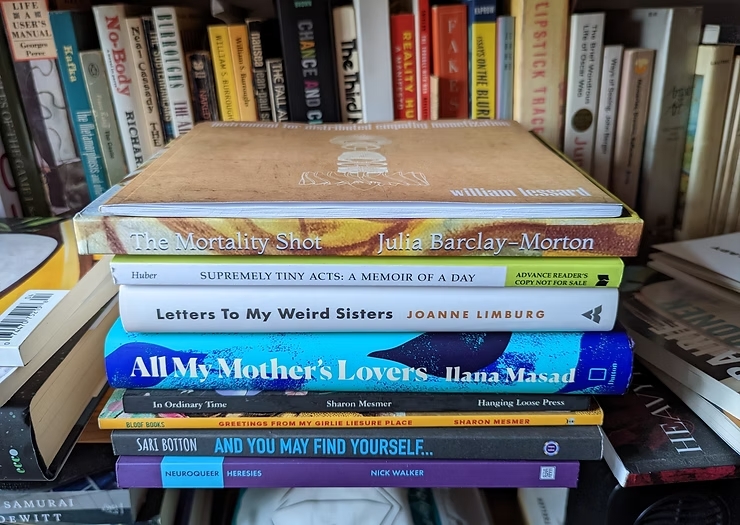

I interviewed writer Julia Lee Barclay-Morton about her experience of autism. Julia began as an experimental dramatist in New York, moving to the UK to

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

One Response

This is a deeply stirring piece which I will read again.