Part 2 MARK STATMAN: MEXICO AND THE POETRY OF GRIEF AND CELEBRATION

Part 2 of my interview with Mark Statman looks closely at Mark’s Latin American poetic influences, his life in Mexico and ends with an extract

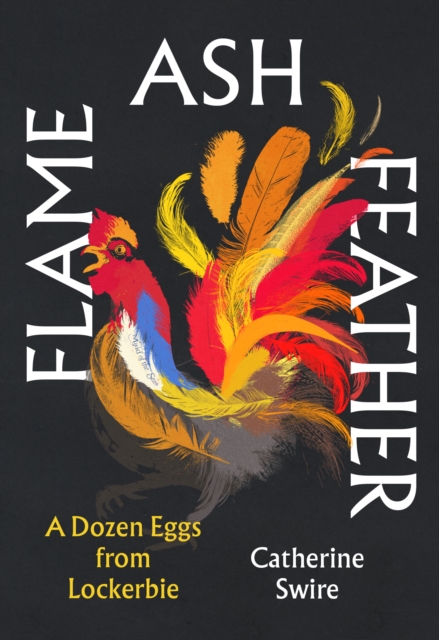

I interviewed Catherine Swire about her prize-winning hybrid book, Flame, Ash, Feather, published by Black Spring Press, that describes keeping chickens and how they translate violence. Catherine’s life changed forever the day her sister died in the Lockerbie crash; suddenly unable to read, yet in her second year of an English degree at Oxford, and with everything that had felt solid now destroyed, she strove to understand the loss and the suffering.

Catherine’s work has appeared on Radio 4’s Ramblings and at the Ledbury Poetry Festival. She is the author of a previous collection of poems, Soil, published by the Artel Press and illustrated by Marina Kolchanov; she also has an upcoming fiction, Air Loom.

Leslie: How did your book Flame, Ash, Feather: A Dozen Eggs from Lockerbie begin, grow and develop? How did you protect yourself while channelling all those difficult feelings into words?

Catherine: Flame Ash Feather is a short book, exploring some of the effects of losing my sister suddenly as a young adult and also my relationship to birds.

I began writing it in lockdown. Something about everybody living in the house, including my late teenage children, was both protective and also required a kind of presence that prompted this kind of work.

We were all preparing Zoom presentations, to friends and more distant family members, on things we felt passionate about (like Florence Nightingale, badgers or olive trees); not just to entertain ourselves, but as a kind of longing to share something more of ourselves, now we were forcibly physically separated. I think this book borrowed from that atmosphere of showing something private but at the same time vitally connective.

Honestly, I have been protected by thought. Through reading the work of many writers and thinkers and working in their imaginary presence, over decades. Certain books felt very close during writing Flame, Ash, Feather. I wrote the book physically and swiftly, into a notebook, in timed episodes, and did not edit it much. It felt direct – a gift out of much darkness.

Teaching has protected me too – when I wrote this book, I was teaching Civil War poetry, Virgil’s Eclogues and Marvel, looking at the way violence is translated by nature. This work led me again to a book written in the aftermath of Civil War, the Compleat Angler. The quiet, observational power of Isak Walton’s work on fish, accompanied me as I sat down to write, intently, about chickens – and my own life.

Finally, and above all, being out in nature and bonding with animals and birds protected me. I feel very hefted to certain landscapes, both in the Midlands and in the Isle of Skye. They have been with me, a guiding continuity, my whole life and I walk and walk in familiar dialogue with them when I need protection.

Leslie: How has writing this changed your feelings? What unexpected effects has it had on you as a person?

Catherine: I think, very slowly, it helped me hold and better allow and trust my own responses to my sister’s sudden death and to acknowledge my difference from my family. I also think it helped me let my marriage go and to accept my need to be more open.

To be honest, most unexpectedly, I use the patterns I make in this book regularly; for example, this week. At the start of January, an inaccurate and depressing docuseries about my family, into which millions of pounds of marketing has been poured, was released in this country and America. After much grief (I had asked for my role not to be played) I chose to speak out briefly against the film company’s project in a national newspaper. To do so, I consciously used the book’s central model of setting cunning against cunning, potentially an activist model; speaking the language of the fox to make it release the white chicken. Afterwards I really did feel stronger, as if I had – with the help of many others, including the paper who, within the pressure of reportage, generously allowed me space to publish about my sister without linking back to the images of the crash – set myself a little freer.

What I would most hope is that the book offers life and a tentative model for speaking truth to power without animosity. It is a pattern for a kind of taming, or recuperation (re-coop-eration) after a very wild flight.

It was important to me in this, very small, book to write in a way that communicated complex, exciting and unusual ideas so that they felt friendly, alive and accessible – immediate. I’ve felt thrilled when, as has really happened, people from very different backgrounds, cultures, sexualities and beliefs, have responded by reading it voraciously, or if people tell me they keep the book by their beds – or have given it to people they loved.

In life-writing, the prism of the ‘self’ allows you to bring a field of ideas and emotion together in a very naked, lit way. When people from connected fields of writing who I respected, loved and responded to this work, I also felt more deeply connected with worlds that I thought I had to lose forever. Completely unexpectedly, also, to my deep pleasure, the book bought some of the people I directly referred to, who I had loved and missed, back into my life.

At the same time the book upset some people in my family. More in truth than I had anticipated because I agreed to surrounding interviews – which may have been a mistake. So I had to face condemnation. I was obliged to close down media opportunities as a result – that was hard to accept, because however flawed I believed in the book’s work. I had tried to tell the truth very carefully, knowing truth to be a feathered and ephemeral thing. I had also shown it to the central protagonists beforehand to get their permission. Even so the book was perceived as a threat. This made me sad and also feel more separated.

Leslie: What do you think you’ve learned about love and loss from this experience?

Catherine: One of my favourite poems describes ‘my heart in the book’ and I learned with renewed energy, as I retold the story of losing the power of reading and writing, how deeply and centrally I love language; its spin and its profound, dangerous game. Writing the book focused my awareness of the isolation of radical loss and how it can make you hyper aware of language use. Because my book was criticised by my family, I learned that for all its faults it was part of me, almost as a child, and that I would stand by it, as a sign of myself in that moment, even if it meant ostracisation.

I also learned, that this book was not, to my surprise, as I felt it at the time of writing, a final word, but a stage in my own journey of mourning; one that for me, I now think, has necessarily been impeded by incessant media exposure – and my concurrent avoidance – over decades. Since writing this book, emotionally, I have certainly gained a deeper awareness of my sister’s presence within me, her power, and with that a deeper sense of my own agency. Sometimes it seems, that the whole work of writing in loss, is to rebalance the relationship between the living and the dead.

I have always loved animals centrally and passionately. Our big, very kind, dog Beowulf lies nearby. Through this book I learned you can make a very small but practical difference to what you love, through writing, righting. Alongside my collection of landscape poems or walks Soil, through my writing, I have been able to lead workshops for adults, young people and children, and to support charities that help protect animals from industrialised farming. I have met a community of poets and contributed to publications as diverse as the Big Issue and the Telegraph.

However reading Flame Ash Feather, five years on, I can also hear very loudly, through the voltage and comedy, the damage the writer has suffered and the sound of death’s flap through the words; for how long can we tell death to ‘fuck off’?

Leslie: Given that hens play a major role in your book, what have been the most surprising discoveries you’ve made about them? How has that changed your attitude to other forms of life?

I’m fascinated by the way birds communicate emotional bond differently from mammals. (Although, incredibly, pigeons of both sexes, produce crop milk, or throat milk – what a perfect poetic symbol!) Particularly regarding touch, perhaps because they largely operate in the airy dimension of the sky and their chicks emerge from sealed shells. Birds are mothered by nature and weather in a different way and yet maintain very close passionate ties in a way that interests me.

I’m also keen to discover more about the way birds, chickens, but also bees, which we keep, communicate emotion, at least to mammals if not to each other, as a communal body, through movement and shape. As a human you can tell if a free swarm of bees feels vulnerable and needs help – so you can touch it even without gloves – just by the way it expresses itself. I find this kind of collective sign making, often in extremity, very moving and a way of understanding other kinds of equivalent cultural behaviour.

When I briefly joined a Tibetan friend in North India, I remember wondering at her very different community of Buddhist monks who cried for dead moths on the temple floor and who openly shared collective dreams. They were generally much more confident and articulate about communal intuition. Stories of our chickens connected us and helped me participate. More and more I want to focus on connection with all feeling things, plant and animal, it is so easy, for any of us, to trap ourselves in false hierarchies that are not connected to the earth.

For me, personally writing about chickens has allowed me to understand some of the effects of trauma in my own response to the world more deeply. More generally, I think chickens in their disempowerment, their humiliation and their dispensability – and their will to communicate – represent something vital about being. We hear a lot at the moment about the Wild and Re-wilding but for me one of the most fascinating things about that important, but somewhat romantic, idea is the way it connects with what is banal and contaminated. Also, perhaps, in ourselves and others, what we need to tame, in order to act meaningfully. Chickens like many pets occupy a kind of demi-wild, or liminal space, which opens up that discourse.

Leslie: Tell us about your development as a writer and how you discovered your authorial ‘voice’.

Catherine: I lost my voice, simply could not work out how to speak, when I was in my early twenties. Writing therefore has sometimes become a way of thinking and speaking with my hands.

Because of that, writing feels more central to me than perhaps to many people – I think my authorial voice developed with the pleasure this daily weaving with my hands brings. For me writing and reading deepens and slows thought, in a way that speech alone cannot. The borders between writing and speech seem to me very permeable.

As I hope the book, through its last chapter, shows, my authorial voice was discovered through engaging and participating in the work of the mind, which, if it can stay humble and supple, can find friends and connection in the most isolated and appalling situations. I studied literature and so learned to assess what kind of writing I found empty, and what valuable, quite formally. I think traumatic experience and isolation perhaps made me fiercer than most about what I did – and did not – want to write.

I also with immense gratitude acknowledge the teachers and guides who could hear and value my voice at a time of great difficulty and who taught me what authority was – and wasn’t. Without their extraordinary help, I think I would have despaired – and still feel silent.

Leslie: Who has influenced you and how?

Catherine: When I was young I particularly loved medieval poetry, the medieval word for despair is wanhope or pale hope – you can, already, hear the shift in that translation. When my sister died, I was studying early English very intently which is perhaps why it burned so deeply into my bones. I find a particular kind of comfort in ancient language and still very regularly read the Gawain poet, Langland and a number of the early mystics – so Sue is right! My former tutor, at Oxford, Helen Barr, who has recently published a superb, funny translation of Patience, by the Gawain poet, was the deepest human influence on my reading. In a world of intense competition – Oxford University – she embodied clear sighted empathy and a skilful, informed interest in restorative language; a genuine interest in healing. I researched and wrote on Piers Plowman, a poem I love, which concerns the Malvern Hills, where I now live looking out on the ‘Field of Folk’. Also A Revelation of Love, by Julian of Norwich, a book which in its quiet good sense and deconstruction of pre existing hierarchies into living kindness – its owning of oracy, right at the heart of writing – is still for me a nightly read.

I also wrote on Christan de Pisan, France’s first professional woman writer. In the early fifteenth century she called for women to share their stories of strength to protect themselves and describes her own experience of grief as a kind of gender fluidity – from female to male. She was the only person to write creatively about Joan of Arc during her life time. In a world of death cults around beautiful young women, completely askance of who they were when alive, I found her good sense, comedy and some of her political thought, uplifting.

I read a good deal of philosophy, including Hannah Arendt, Heidegger, Hegel and Derrida. I’m also, for obvious reasons, interested in thought and theory around terror and reportage, including the work of Deleuze and Guattari, Debord, Virilio and Badiou. My sister was killed and I lost speech, at an exciting but complex point for thought in the humanities when old models of identity were breaking down fast, I found that the knots of post-modern thought in particular, held me to text, by the snags of their complexity; in a way that flat words did not, I just slid off them.

My grandmother, Otta, was a writer and sometimes comes to me in dream. She lived in the isle of Skye and collected traditional stories of Skye and of the Highlands, including many local oral tales that were getting lost as story telling dissolved into radio. Many of those stories, including of mythical creatures, are very familiar to me. I’ve spent time in Skye since my first childhood; our area is also Viking country, full of Norse names, so it connects me back to the early poems that influenced me.

I fell in love with Toni Morrison’s Beloved – from when it was first published and I was young. I loved what Morrison did as a writer, the generosity of that book, as well as the rich play of language. Although her work is obviously, primarily and overtly, concerned with race and America’s history of enslavement, with all its binary oppositions, through the motif of Beloved’s ghost, it also quietly makes a shape to understand other kinds of slavery – and for release.

I love the way that since I was young and lost language, thought has wrestled to find new ways to connect with the earth and with climate in crisis. At the moment, I’m reading Samantha Harvey’s Orbital, a beautiful contemplation of the world and weather, from space. In a way, it reminds me of Julian of Norwich’s vision of the world as the size of a hazelnut in the palm of her hand. They are both meditative exercises in empowerment through detachment and reconnection.

ABOUT LESLIE TATE’S BOOKS:

Part 2 of my interview with Mark Statman looks closely at Mark’s Latin American poetic influences, his life in Mexico and ends with an extract

I interviewed international poet and translator Mark Statman about Volverse/Volver, his 14th published collection. Mark, who has won national arts awards, is Emeritus Professor of Literary

I interviewed Lisa Dart, finalist in the Grolier, Aesthetica and Troubadour Poetry Prizes and author of The Linguistics of Light (poems, Salt, 2008), Fathom (prose

I interviewed writer Julia Lee Barclay-Morton about her experience of autism. Julia began as an experimental dramatist in New York, moving to the UK to

I interviewed Gillean McDougall from Glasgow, who edited the collaborative projects Honest Error (on Charles Rennie Mackintosh and his wife Margaret Macdonald) and Writing the

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |