Part 2 MARK STATMAN: MEXICO AND THE POETRY OF GRIEF AND CELEBRATION

Part 2 of my interview with Mark Statman looks closely at Mark’s Latin American poetic influences, his life in Mexico and ends with an extract

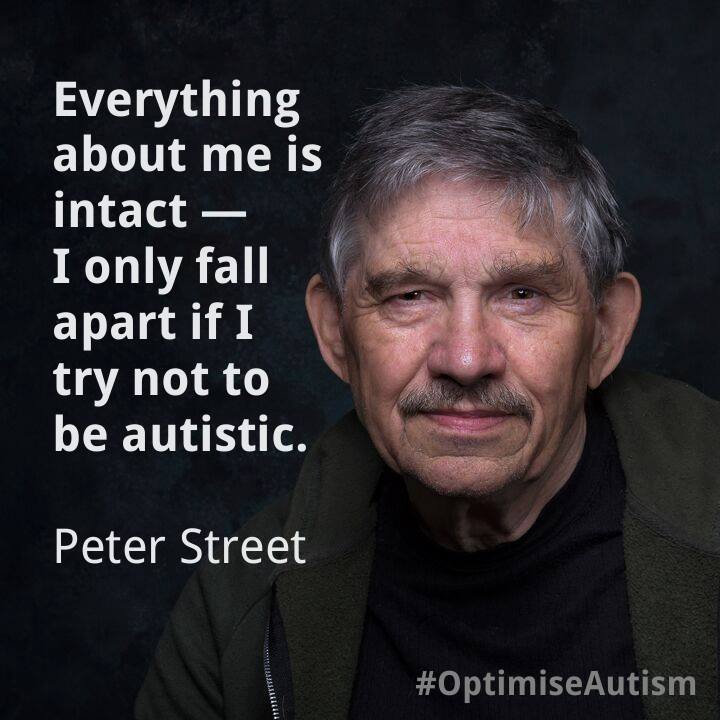

I asked author Peter Street to speak about his extreme experiences as a gravedigger and talented, autistic poet. What follows is a shocking, surprising, expressive record of survival against the odds.

Peter says about himself: “I left school barely able to read and write. I have very little logic which has held me back lots of the time, but it’s also given me a kind of freedom. It has separated me from the rest of society – I don’t feel a sense of failure or fear. I keep saying I was born outside the box.”

Peter has been a writer in residence in schools and prisons and was nominated for the 1993 Forward Prize for poetry.

Leslie: You say your life has been at times brutal and turbulent but mostly beautiful and exciting. Can you take us through the extremes of your childhood/schooling and early adult experience as an arborist and gravedigger, please?

Peter: In the 1950’s there were no rules, no information regarding autism.

In March 1948 Mum was sexually abused and I was the result. Her family refused to support her. In those years what ever happened to an Irish Catholic woman in an Irish Catholic community was all her fault and she refused to take the penny royal to abort me. Mum gave up everything for me. The abuser was forced to do the decent thing and marry her. Getting her own back, she jilted him at the altar. I’m mentioning this because I had no aunties, uncles or siblings which made me more resilient for everything life was going to throw at me.

Brutal: from the other kids: The ear bashing and over-powering pains were a sort of drip, drip invisible pain which sort of stopped me in my tracks and filled my mouth with: “Can you please stop shouting and please move away.” That’s what should have happened, instead, my lips snapped shut and all the words/letters, full stops and God knows what else just bumped into each other and reversed down into a sickly lump in the bottom of my belly.

Not Being Me

– For everyone on the autistic spectrum

Childhood nights were dreams

of being a sheep

then up and outside of a morning,

a quick check to see

if by any chance in the night

there had been a change

of being just like all my friends

and not the odd one out

like afternoon dance lessons

spent hidden

in the toilet

out the way because

I couldn’t dance the sheep steps

that’s why I dreamed

of being a sheep

so I could be like everyone else.

Teachers: From from the age of about seven/eight they would make me stand in the waste basket and at times I was hit across the head with the board duster.

Mum Diary: Peter came home crying: teacher made him stand in the corner all lesson because he couldn’t cover his book with the newspaper, he couldn’t fold the paper the right way. Or even understand why. l’ll swing for that school one of these day

Whenever the teacher started to teach a big hole in the back of my head would open up and everything being taught would enter and then trickle down between my shoulder blades ending up on the floor in little mountains of learnings.

Sheep Inheritance

I am a sheep

That’s what the family call me

A black one. I have tried painting myself

a colour they want me to be

gone through all the rainbow

each one just seems to slide off

like its not meant, not suited

worst still I’ve dripped all over their best

carpets, stained, for everyone to see,

talk about, while they chew and swig down

A bit more bigotry. We were visited out of the blue by a Jewish woman called Abrahana who had escaped the Nazis with her daughter Rachel. On those visits Rachel, who was about four years older than me, would practise her make-up skills on me and in return I would plait her hair in ways we were all different from the norm of the community. Rachel and I would walk up into the park where we had our secret den. We would share our trauma. Rachel would cry and cry about going back to Holland but there was no-one there who she would know, the Nazis had seen to the that.

Another Sideline – 1957

for Thomas Edgar Street

Two shillings

for every dead dog or cat

run over poisoned even shot

would be waiting with heads on

heads off maybe other bits

missing every time

my nine years entered

the fire-hole where sulphur

smacked me in the nose

Dad would clang open the

incinerator door turn

pick up Rover or Tabby

he kept separate from the coal

with a clean cloth

he would first wipe off

any dirt or blood

then giving them a last stroke

he’d throw them in

and I would watch

someone’s pet melt into nothing.

Turbulent: I was lost in a strange world where everyone was different from me. Where boys/girls of my age could do woodwork, metal work or maths, unlike me. OK my reading and writing was very basic but I was able to do some. My two best friends who never left or abused me were the large red brick wall in the back street where I lived and the other was the outside toilet at the bottom of the back yard. After much training with my red brick wall I graduated to goalkeeper for the school and for mid-Lancashire under fifteen. There was talk of me having a trial for Lancashire and then maybe England under fifteen – but then my epilepsy kicked in and that was the end of my football career.

Leslie: How has nocturnal epilepsy affected you?

Peter: My epilepsy has only been nocturnal for about the last fifteen years. I began work as an epileptic – my first job was in a bakery that lasted four months I was dismissed because I had a seizure in the bakery. I had the same treatment in jobs in a warehouse, a butchers/slaughterhouse, a paper mill and working as a milk boy.

Most of the time I was on my own which I preferred. I have never been lonely.

I had started to dream about girls. Dating was a nightmare, I wanted to be with a girl but I didn’t want to touch them and I didn’t trust them after I was brought to believe they trap boys my age and give them diseases and they bleed once a month.

Going Back

for Margaret Macmurray.

I switch off the ignition,

the other side of their clipped privet hedge

and taste again her last kiss

in Aberystwyth

where her breast pressed

into me.

I was fifteen years old,

embarrassment growing harder.

I pulled away, and she

pushed back into me.

We danced this strange dance

at the back of a chippy

where the taste of her red lipstick

survived the fish and chips.

At eighteen my life was becoming more beautiful. I met Sandra who I immediately felt safe with. It was then that I realised the two of us were going to be one. We needed money to buy a house of our own.

Mum at best wanted me to be a Jesuit priest at worst a parish priest – I became a gravedigger and exhumer.

The seven other gravediggers were all men who were on the fringes of society. They included a bare-knuckle fighter and an ex-marine, door bouncer who thought he was God’s gift to women. Suddenly my life opened out. I was the baby of the crew. Epilepsy was nothing to them. They mothered me, played pranks on me, and the banter was wonderful and very funny. It was the first time in my life I felt a part of something.

StillBorn

for Jenny

I piss on my hands

to ease the burning

from blisters and frost

stream in a warm few seconds

dies of cold

I’m tunnelling underneath

the family headstone

stacking

cubes of oil-black clay

onto the wooden staging as

black beetle funeral cars creep in

between angels standing either side

of cast iron gates

I take from Jenny her baby

and slot him under list of names

into Dearly Beloved Grandfather arms.

Leslie: How did your life continue and change after that?

Peter: I was a gravedigger for four years until I had a severe shoulder injury. I somehow became a gardener and took to it even the botanical names. This was in 1975.

With my epilepsy, I was now getting about a one-hour warning (Aura) before my seizure so I took the gamble and blagged my way into college to study arboriculture. I never told them about my epilepsy – or the fact I could barely read and write. I failed in everything to do with the class room but passed on my practical. I was a qualified arborist and became known for taking down dangerous trees over hanging buildings etc.

In 1983 Sandra thought I’d been taking the gamble of climbing trees for too long. So I managed to get a head gardener’s job in Kent, but I had a couple of seizures there and the owners couldn’t cope.

Back home, I fell from the back of a wagon and broke my neck. Luckily the fractures went down the side of the spinal column. While in hospital for six months I was in the next bed to an English lit teacher and that is where my learning how to write began- my first poems to him were about trees. I was in a wheelchair for about two years, and walking was acutely painful.

Leslie: How did poetry begin, grow and develop in your life? What’s distinctive/yours about the poetry you write?

Peter: I tried O’ levels at college but failed both times. But I had found Charles Causley and poetry. The college lecturer/poet John Cassidy, who had introduced me to the poet Matt Simpson, agreed an arrangement that I’d advise on his garden and do the odd special meal for birthdays etc and in return he would teach me about writers and poets. It soon became clear I didn’t understand about punctuation/grammar. It was Matt who first spoke the word ‘Autism’. He called me a paradox because I enjoyed the writings of James Joyce and I could talk clearly about ‘Crime and punishment’ or Orwell, but I didn’t understand full stops, commas etc. Not only that, but he had to give me instructions how to drive home because I can’t manage reversing. He also introduced me to e e cummins, Ezra Pound and Robert Creeley. (Two years ago I gave a talk / abstract at Liverpool University about how poetry is the perfect art form for those on the autistic spectrum because there are no rules.) Total freedom.

The BBC invited me a few times to talk about disability. Soon I was asked if I wanted to have a kind of trial to see if I was a suited to go in on a regular basis. I was given a newly-released book on anthropology – I’d never heard the word – so I asked Matt to review it and I read out his comments/ review on BBC GMR and I was accepted.

Leslie: What parts of your YA novel ‘A Kind of Village’ are adapted from life? What did you change and why?

Peter: Part of ‘A Kind of Village’ draws on my feeling of safety in a cemetery – maybe it’s the calm and loneliness. In some ways I think the book is quite Quakerly because it’s about love and forgiveness. There are three main characters, all young: Thomas, the protagonist, who is both autistic and epileptic, Pauline, who cares for her seriously disabled mum and Billy, who we at first see as someone who is a bully, but he has love in his heart.

Thomas has long auras, or warnings before a seizure. Anyone who has experience of these is both awake but in another world. That other world is the cemetery which Thomas sees as a kind of village where all members of a past community live. While in his aura, he sees them, brass bands and tribute Led Zeppelin bands playing ‘Custard pie’. He also sees coffins lids being lifted off when new members are brought in to meet their friends, lovers and they dance and have parties. The idea came to me after seeing the Stanley Spencer’s painting ‘Resurrection’.

Leslie: What was the effect of having no autistic diagnosis until seven years ago?

Peter: When an incident brought back my post-traumatic stress disorder, a doctor suggested I see a therapist based in our local hospital. After about six sessions she suggested I see a consultant colleague who specialises in diagnosing older people on the spectrum. Walking home after being diagnose I cried happy tears. All of a sudden my whole life made sense. All those beating I took at school – now I knew none of it was my fault.

Leslie: You say, “My autism has made me who I am.” Given that autism is a spectrum and different for everyone, can you describe how it has affected you, please?

Peter: Loud noises are a problem. Sandra bought a new hoover one which was quieter because of that. I cannot cope with dirt. For instance, all our years of marriage we had words about things being stacked up in the shelves. We discovered I like everything spread out landscape fashion. We couldn’t understand why I had to have my own cutlery. Dining out was/is a nightmare for me. One example is when I went to a meeting in an old factory where all the furnishings had been given to the group from the charity shops. The settee with was dirty and greasy, and the same with the carpet. My neatness/cleanness habits got the better of me and I had to leave and have not been back since.

One of the worst things for me is if I click the wrong button when I’m typing on my computer. When that happened, I used to beat my leg until I could barely walk. To deflect that I had to go into the shed where I had a baseball bat and I would knock shit out of a second hand cushion we found. The consultant said it was partly because of my high intelligence that I cannot cope with doing such simple things wrong.

But since my diagnosis I haven’t beaten or abused myself at all. High intelligence!!! I had found who I was – oh my I did cry happy tears.

Next week I interview writer, speaker, musician and software expert Jess Ingrassellino .

ABOUT LESLIE TATE’S BOOKS:

Part 2 of my interview with Mark Statman looks closely at Mark’s Latin American poetic influences, his life in Mexico and ends with an extract

I interviewed international poet and translator Mark Statman about Volverse/Volver, his 14th published collection. Mark, who has won national arts awards, is Emeritus Professor of Literary

I interviewed Lisa Dart, finalist in the Grolier, Aesthetica and Troubadour Poetry Prizes and author of The Linguistics of Light (poems, Salt, 2008), Fathom (prose

I interviewed writer Julia Lee Barclay-Morton about her experience of autism. Julia began as an experimental dramatist in New York, moving to the UK to

I interviewed Gillean McDougall from Glasgow, who edited the collaborative projects Honest Error (on Charles Rennie Mackintosh and his wife Margaret Macdonald) and Writing the

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

6 responses

I really enjoyed Peter’s poems and his journey to discovering he is autistic. I can imagine it is very difficult to go through life undiagnosed.

Yes, Peter’s poems are great and his life story is remarkable! 🙂 🙂 🙂

What a man – what an inspiration to never give up – hope arrives so unexpectedly- I’m so glad he found his Sandra and caring mentors. Love his poetry too – great interview – thankyou for introducing him to us ?

Thank you for responding with your heart! Leslie xxxx

Excellent interview with Peter Street! His life story is inspiring and his poetic voice is unique.

Thank you, Beth. Yes, I thought so too. It’s good to come across poetry that is ‘outside the box’.