Part 2 MARK STATMAN: MEXICO AND THE POETRY OF GRIEF AND CELEBRATION

Part 2 of my interview with Mark Statman looks closely at Mark’s Latin American poetic influences, his life in Mexico and ends with an extract

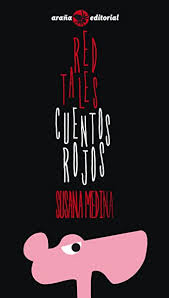

I interviewed writer, artist and filmmaker Susana Medina winner of the Max Aub International Short Story Prize. Susana is a multi-lingual author and poet who has published several volumes of radical, experimental writing. Her work was featured in Best European Fiction, 2014. Susana has curated international art shows, translated for English PEN, Writers in Prison Programme, and has studied at DAMS , Bologna University, under Umberto Eco and Dario Fo. Susana is also a climate activist, taking action and appearing on stages for Extinction Rebellion UK, including the Edinburgh Fringe. Currently, she’s writing with Roc Sandford We Are the Asteroid, We Are the Dinosaurs, a dialogue about climate change and ecological collapse, which covers all the rebellions up to date.

Leslie: Looking back to childhood, what developed your creativity? How did it grow and develop?

Susana: Let’s say, as a child I was interested in doing things differently. My Czech grandmother sent dye for Easter eggs, and I’d use it to make purple spaghetti. There was a summer I decided it was cool to wear a colourful handkerchief around my ankle… I put lots of tangerines on my bedroom table and left them there for a long time, as I liked the visual effect. So, unknowingly, that was my first installation. There was a gorgeous abandoned mansion at the end of my street. And I’d invent horror stories for my friend, passing them off as true. I was always attracted and fascinated by what was different. Possibly, an impulse towards innovation motivated me to seek it out. Transforming things also interested me, translating one thing into another. I wanted to be either an astronaut or a vet.

I was brought up in Spain in a multilingual family, with a constant awareness of two other countries by comparison: Germany and England. It made me aware of the relativity of customs and ways of seeing the world. My German-Czech mother read me fairy tales from Hans Christian Anderson, which I loved. My parents gave me a strong sense of the social injustices facing the world. They were funny and good storytellers, and my Spanish grandmother, who only went to school for two months and learned to read and write in that short time, was a born performer, who sang and recited poetry for the family. I was good linguistically too, but at school there was no creative writing. I was really into art and, aged 11, won a regional prize for my mixed-media contribution: a poem and a drawing about homeless gypsies with their backs to the viewer and a child on a potty. The theme of the prize was hunger and the third world, but my work was about the gypsies who lived nearby. Let´s say, from an early age, I was interested in injustice and ‘the other’. Then, aged 14, we had creative writing assignments, and I got top marks for my stories, and was awarded a couple of literary prizes aged 16. So, these things lured me in a certain direction.

As a child, I had recurrent hypnagogic images as I was falling asleep, which filled me with a sense of wonder. I would see cartoon-like pictures of reality, with the black silhouettes becoming thicker and thicker until the blackness almost devoured the image. And then, images of sublime light and lightness. So, heaviness and lightness, beauty and ugliness. This was so strange. It made me take an interest in the mind.

My mum’s chronic affliction is epilepsy. She’d have a fit or so a year, sometimes, less. Every so often, I looked after her. After a fit, she was unconscious and occasionally, she spoke in a mix of German, English and Spanish. It was like multilingual nonsense poetry. It was an encounter with something radically different, beyond the conscious mind. This made me realise there were other worlds that couldn’t be understood. My interest in the mind, neuroscience, surrealism, the irrational has its root here. It made me wonder, made me so curious. Also, when I looked after her, I realised going to school was non-essential.

Pippi Longstocking, the film series, was on Spanish TV for years. It was crucial for the development of my creativity and personality. It gave children freedom and independence of thought. This was Franco’s time. It was certainly empowering for little girls. It fostered other ways of being, embracing chaos and a rebellious spirit.

Reading Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass, who I’ve mentioned in a few interviews, made me into a writer. I was sixteen, I found it mind-blowing. To write a book and have such a transformative effect on the reader was something marvellous to do.

Leslie: How would you describe your creative personality today (and what you love to do…)?

Susana: Like many people, I see creativity as a general attitude to life that informs choices made or not made. Everyday life should be as creative as possible. Ideally, our rapport with others should be creative. I love transforming things, clothes, jewellery, things around the house. I’ve been upcycling since I was a child. It’s a challenge, to come up with an idea to improve on an existing object. It’s something I do spontaneously. I suppose it is relaxing and much more immediate than the long writing projects I tend to work on. I used to love cooking special dishes, though of late, I rarely do it. Too busy.

As to my writing, I read lots of articles on different subjects I’m interested in. Ideas, words, sentences for different projects pop in my mind, and I write them wherever and then type them up in the right file. I sit at my desk and write and edit for as long as I can. A lot of time is spent fixing problems, trying to come up with solutions, looking for the right word or feel. When things aren’t going right, I sit on a long chaise that I bought for writing, and let writing and ideas flow, suspending judgement, or go for an extra walk.

In the early 90s, I went through a bit of writer’s block and devised a system of writing long drafts for stories and books, and then I would set them aside, allowing them to lay fallow for a year to let the soil ‘rest’. The idea was to have a stash that I could always draw on. And so, there are new ideas, and there’s always the stash, never the void.

Leslie: Which of your creative works best exemplify your own quote, “Coherence is often confused with homogeneity. In order to be coherent, art should shoot in all directions”? Please introduce these works to us as if we were an audience who know nothing about what you do.

Susana: When I wrote that aphorism, a long time ago, I was thinking of different things: to embrace the multiplicity of reality, to embrace contradiction, to explore psychological excess, taboo subjects, unearth the unexpected. My book of short stories Red Tales shoots in a few directions. It tries to fuse poetry with fragments and a narrative, while the initial idea of each story is an art installation. For a long time, it was titled after the pronouns, I, you, she, we, you, they… and each story was written with a different pronoun. When it became Red Tales, that changed a bit, but embracing diversity and different points of view is at its core.

I was also thinking of one’s trajectory as an artist. Different ideas might call for different fields, disciplines. I had discovered I like hybridity, eclecticism. Although I have always focused mainly on writing, and some of my art ideas, slip into my writing, my approach has tended to be transdisciplinary, so, I have done curating, artworks, films, self-portraits created for the net. For instance, when I did my PhD on Borges, I approached my doctoral thesis as part of my literary trajectory, though it was subjected to some constraints. For the sake of texture, I wrote a chapter using a naive voice, and ha ha, I had to re-write it.

The aphorism you quote appears in ‘Medinations,’ a section from my Souvenirs del Accidente, that juxtaposes traditional and experimental poetry, ballads and aphorisms, creating sharp contrasts. When I wrote this ‘medination,’ I was also having a jibe at a certain type of anodyne novel that promotes tame narrative and sober ideas, rather than a feisty and plural writerly voice.

Leslie: With such a large body of written and visual creations, can you draw out the main themes common to all your work, please?

Susana: What it is to be human… innovation, a poetic impulse, humour, gender, difference, social injustice, transgression, rhythm, art, dreams, adventure… But then, each work has its own specific themes. For instance, in Philosophical Toys, the main theme was our relationship with objects… Spinning Days of Night, which I have been writing for more than twelve years (with lots of interruptions) and have just finished, is about sound, silence, illness, being bionic, becoming a cyborg…

Leslie: Can you describe your own seminal influences, please – the most important ones that you have learned the most from. Which cultural traditions do they draw on?

Susana: I’ll do it in chronological order, which roughly coincides with early fascination. Dante’s Divine Comedy, for the surreal imagery and feel, the strong sense of structure and the knowledge of our vices (in terms of structure, it informed my book Red Tales). Hieronymus Bosh, ‘The Garden of Earthly Delights,’ for its wild imagination and inexhaustibility. Cervantes’ Don Quixote, for adventure, existentialism and drawing on the Spanish Picaresque, which is fascinating; Jonathan Swift’s works for imagination, humour and political satire; Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass, for its celebration of all life, its pantheism; Fernando Pessoa’s Book of Disquiet, for writing with fragments; Frida Khalo’s oeuvre, which I discovered when I was fourteen, for introducing me to surrealism; Marguerite Duras’s The Lover, for desire and synthesis; ‘Space Oddity’ and ‘Hunky Dory,’ well a lot of early Bowie, really, for emotion, beauty, youth and consolation; Wim Wender’s ‘Wings of Desire’ is my favourite film, its poetry is exquisite; Cindy Sherman for her endless re-invention of female identity in her self-portraits.

The above are early friends, but many voices contribute to the collage we are. When I was studying History of Art, I really got into female artists such as Hannah Höch, Meret Oppenheim, Sophie Calle Jenny Holzer. In other interviews, I’ve mentioned more writers: JL Borges, Samuel Beckett, Italo Calvino, JG Ballard, Angela Carter, Julio Cortázar, Paul Auster, Octavio Paz. There are many artists from other disciplines I am interested in, who might have shaped my work. We learn from everything. Beyond learning, my rapport with the artists I mention is one of fascination and love.

Leslie: What are your creative processes? How do you work on a project? What are your personal routines that help to keep you creative?

Susana: Daydreaming is an essential ingredient to the creative process. So is hard work. I take both very seriously. I have an idea and start thinking about it. I try to see its shape. I sit at my desk, take notes, doodle and look out the window a lot: some plants, trees and sky, maybe a squirrel running up a tree, a magpie in flight. I write one word and then another one and so on. It is a delicate and careful process. I read a lot on the subject. I spend a fair amount of time untangling chaos. Sometimes, there is flow, sometimes, there isn’t. When there isn’t, I tend to meditate.

I take daily walks, listen to music, go to the garden, play with the cats, caress them. As to my artworks or self-portraits, they are completely spontaneous.

Leslie: Who are your creative heroes – why them?

Susana: Nature. Do I need to explain?

Artemisia Gentileschi, one of the few pre-twentieth century female painters we know, from the Baroque period. She was an extraordinary painter and managed to turn trauma into extraordinary paintings. She was raped by her mentor, there was a well-known court case, in which her father, also a painter, stood by her. In her paintings, we see the trauma of being raped from a female perspective. Talking about the alchemy of turning sorrow into gold, I’d say I really admire Frida Khalo, for systematically speaking about illness and disability in her surreal paintings, and conveying strong vulnerability. As we are in the middle of the Black Lives Matter uprising, I must say there are three singers I have enjoyed throughout the years and really admire in their different ways of tackling racism: Billy Holiday, Ella Fitzgerald and Nina Simone.

I was hit when David Bowie died and wrote an homage: The Bowie Neurotransmitter. I admire Bowie’s talent, his political activism as song-writing, and ceaseless re-invention, his energy was extraordinary, and his legacy, a gift that guides me. Patti Smith, whose ongoing energy is also extraordinary, I admire her for her feistiness and courage. I love Bjork’s voice, her songs, her experimentation. I have always cherished Joseph Beuys, for his artworks manage to convey spirituality and the sacred. Recently, I discovered an amazing large-scale work of his, an ecological intervention: In 1982, he proposed a plan to plant 7000 oak trees throughout the city of Kassel, each paired with a basalt stone, for documenta 7. With the help of volunteers, he planted them over several years, completely transforming Kassel‘s cityscape. Isn’t it marvellous?

JG Ballard, for his prescience.

Borges, for his ability to create beautiful metaphors.

Leslie: What has been the impact of Extinction Rebellion on you and your work, please?

Susana: On me, enormous. Suddenly, there was a possibility of doing something concrete about climate change, and changing the conversation, which we have. I was excited to find so many lovely people willing to put in their time, creativity and energy. To find so much empathy and altruism… and imagination, and intelligence. Here, something ready-made I said before: ‘The Rebellion embodied the crystallization of a new type of consciousness I thought would mark the new millennium. I knew it was there. But it was only during the Rebellion that I saw it crystallised. On Waterloo Bridge, I had a glimpse of Utopia.’ The cherishing of this new consciousness was also something I had been writing about. These last two years, I had decided not to do readings, interviews, etc, and focus on my novel. With Extinction Rebellion, I made an exception. Tackling the climate and ecological emergency, isn’t something that can be adjourned, so instead, I put on hold editing the last draft of my novel Spinning Days of Night (which in part deals with climate change, ecological collapse and environmental triggers to illness) to be part of the rebellions, and adapted a couple of pages from it to read at the first Rebellion and gave it a new title: ‘Dear Angelus Novus.’ I read it at Eros in Piccadilly Circus, the Oxford Circus #TELLTHETRUTH boat, the Edinburgh Fringe, the Writers Rebel Marathon… I met you at the second reading of it, on Waterloo Bridge, with the Letters to the Earth project, which you hosted. I could be more involved with other Extinction Rebellion actions. The extra commitment of caring for my mother, prevents me from doing so, but now, in the summer, I’ll have more time.

In turn, the rebellions and civil disobedience fed into the last chapter of my novel, in a kind of oblique way. I also started working with Roc Sandford, on a dialogue about the first Rebellion. We interviewed each other in person and by email. That soon turned into a book covering all the rebellions, which we are still writing, with a lot of interruptions. Hopefully, we’ll finish it soon. We published an excerpt in 3:AM Magazine, which offers an extended answer to your question. We’ll be publishing more. The book is called: We Are the Asteroid, We Are the Dinosaurs. It is my main contribution to Extinction Rebellion. ???

Next week I interview Lisa Holdsworth scriptwriter for TV episodes of New Tricks, Robin Hood, Emmerdale, Waterloo Road and Midsomer Murders. Lisa is chair of the Writers’ Guild of Great Britain .

ABOUT LESLIE TATE’S BOOKS:

Part 2 of my interview with Mark Statman looks closely at Mark’s Latin American poetic influences, his life in Mexico and ends with an extract

I interviewed international poet and translator Mark Statman about Volverse/Volver, his 14th published collection. Mark, who has won national arts awards, is Emeritus Professor of Literary

I interviewed Lisa Dart, finalist in the Grolier, Aesthetica and Troubadour Poetry Prizes and author of The Linguistics of Light (poems, Salt, 2008), Fathom (prose

I interviewed writer Julia Lee Barclay-Morton about her experience of autism. Julia began as an experimental dramatist in New York, moving to the UK to

I interviewed Gillean McDougall from Glasgow, who edited the collaborative projects Honest Error (on Charles Rennie Mackintosh and his wife Margaret Macdonald) and Writing the

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |