Part 2 MARK STATMAN: MEXICO AND THE POETRY OF GRIEF AND CELEBRATION

Part 2 of my interview with Mark Statman looks closely at Mark’s Latin American poetic influences, his life in Mexico and ends with an extract

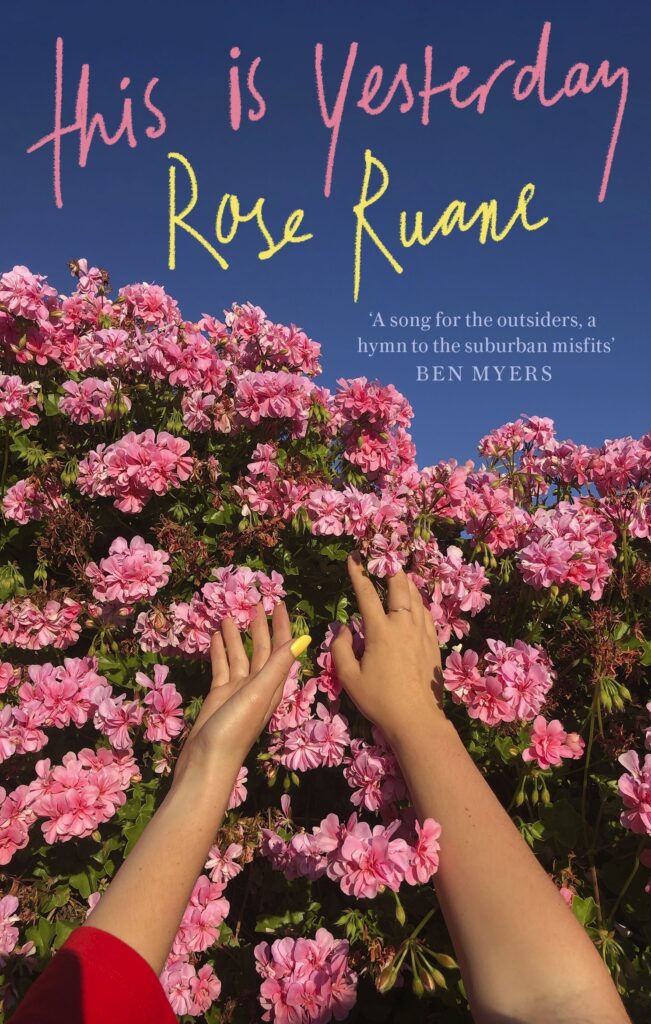

In this interview, writer Rose Ruane tells her creative life story. After a career as a multi-disciplinary artist, Rose reinvented herself as a successful writer, winning the Off West End Adopt a Playwright award. Today, Rose writes plays, makes podcasts, performs spoken word and has a debut novel This Is Yesterday published by Corsair. She lives in Glasgow with her ever-expanding collections of twentieth century kitsch and other people’s letters, postcards and photographs.

Leslie: What led you to originally becoming an artist? Where and how did your talent first show itself and subsequently grow and develop?

Rose: Since I was fortunate to grow up in a household where creativity was encouraged, my earliest memories involve the joy and frustration of trying to conjure something with paper or Plasticine.

With adult retrospect, I was always trying to instil what I created with feeling quality. I recall the disappointment of my skills being unequal to externalising interior experience.

I still get frustrated by the gulf between ideal and actuality, but writing is a space which can hold action and emotion as well as visual elements. I write from Kinokopf; seeing my characters and their places.

At high school I was bullied but art momentarily replaced negative attention with positive.

Children who are appalled by and afraid of your strangeness or otherness still can’t help being impressed if you can draw Garfield accurately.

There was always tension between the fact someone would ask me to draw cartoons on their backpack, then later be part of a group chasing me home, trying to throw mine up a tree.

I’m wary of the urge to make meaning from experiences which were sad and shit, traumatic and violent.

Processing them is already hard work for where softness is most needed, but I do think I learned about the irreconcilable contradictions in human behaviour and how art, however, fleetingly, can shift perspectives.

Leslie: What kind of art did you create? How did it lead to giving up art and becoming a writer? Was it a gradual process, a light bulb moment or a case of denial-but-always-I-knew, really?

Rose: I went to art school as a mature student of 26. Ridiculously, I felt like Methuselah‘s nana.

At 45, I know that at every age, each previous one appears youthful; at 80, 70 will seem a stripling.

Prior to art school, after a serious breakdown and subsequent self-destructive choices, I worked in dull minimum wage jobs, daily being treated as beneath contempt, so I arrived there determined and fiercely grateful.

I was equally cursed and blessed in that.

In one way, my appreciation of having four years to learn about and make art for caused me to exist in a ravenous, happy fever of “where have you been my whole life?”

In another way it made me eager to excel academically; to be “good,” sometimes creating work my heart wasn’t in.

I often think of Frank Bidart:

WHETHER YOU LOVE WHAT YOU LOVE

OR LIVE IN DIVIDED CEASELESS

REVOLT AGAINST IT

WHAT YOU LOVE IS YOUR FATE

It took me so long to learn that truth. Now I live by it as much as possible. I had enough shame and compliance when younger to last me multiple lifetimes.

After art school there was a long slow process of reclaiming artmaking from the institution. Coaxing back the pleasure of making and drawing from theory and critique was bound up in writing.

After I graduated, I briefly had some kind of middling “career.”

I exhibited big, kitsch, latex sculptures of melted-looking wreaths and huge projections of performances to camera exploring gender, sexuality and body image, involving a mixture of nudity, makeup, slapstick and genuine self-harm.

With hindsight, it wasn’t safe wiork safe for me to be making, they were often expurgations of unconfronted trauma and distress.

Besides, most of them were conceptually lacking and not that interesting. Also, a lot of them involved me hitting myself in the face which isn’t a sustainable art practice.

I arrived at an understanding that I’d had all the shows I was going to, without getting involved in a type of greasy pole scrambling which is beyond me.

Complex reasons; some ethics, some shyness. Increasingly, I think, neurodiversity. Intermittently I get mentally ill, and I have a neurological illness which is sometimes disabling.

I’d always used text in art, and as a method of investigating ideas. I’d been writing in a desolate spirit of trying to fill pages and days, when, from the window of a stopped train I saw two women inside a polytunnel. One young, one older, clearly shouting. The older started throwing plant pots at the younger, then the train moved, and they came with me.

That was how I started This is Yesterday, burning curiosity about those strangers, coinciding with feeling either I’d dumped art, or it had dumped me, and it didn’t matter since I hated us both by then.

But, like many lifechanging experiences, becoming a writer unfolded as a series of expediencies and encounters, blundering from one to another without understanding how far I was travelling.

I worked incredibly hard at it, but though that met supportive people who encouraged me. I was accepted onto the Creative Writing MLitt at Glasgow University where I stopped denying I’d become a writer and met my brilliant agent, Jo Unwin.

A fellow student kindly tried to introduce me and I literally power walked in the opposite direction; I knew I could write but hadn’t written anything worth showing her.

I thought “I bet she meets bullshitters all the time and I don’t want her to think I’m one,” but I emailed her the next saying “I’m the one who legged it and here’s why,” Actually, she was interested in me and my work. Now, I understand the moment I emailed her was the moment I admitted to myself that wanted things for my writing and not to pursue them would be self-sabotage.

Leslie: In your novel, This Is Yesterday, Peach, your protagonist, experiences a similar-but-different story to your own. How did you change your personal story to fit the novel and why? Was it forced upon you in the process of writing, planned, chosen for moral reasons, or was your life story simply a jumping-off point for lots of invented scenes & characters?

Rose: Peach’s story has a limited set of similarities to my own. It was never a matter of changing my personal story, more drawing out emotionally resonant experiences and making them available to Peach, and by extension the reader.

We’re both white, cis, deliberately childless, lower middle-class women from the slightly less affluent part of a wealthy suburb, both artists and Manic Street Preachers fans.

But Peach, is straight and I am bi/pan. As a teenager, I was infinitely more chaotic than her; with a mental illness requiring treatment. As an adult, I’m much more stable and self-compassionate than her.

I’ve had years of therapy and confronted my past whereas Peach is still flailing, reinterpreting hers alone amidst a family crisis.

The book reflects on how the teenagers we once were reside within the adults we become; Peach continues reinscribing the same emotions and relations in adulthood as in adolescence as do her family.

I’ve worked painstakingly to stop walking in the world wounds-first and being a damaged person who damages people. Peach believes that to be inevitable and justification for inflicting misery on herself and others.

It’s a huge deal to have secure housing, as I do, and years have passed since I worked purely for financial survival as Peach does.

It’s an open question in the book whether Peach stopped making art because she’s not “good enough” or because of her precarious living situation; job she hates, monstrous boss, power structures which she’s realised (in her own conception) shamefully late, are discriminatory.

I started This is Yesterday before therapy but stalled repeatedly. It’s no coincidence I finished this book, which deals with memory and family, a couple of years into the process.

I’m always in writing about whether change is possible or whether we inevitably lapse into patterns woven into us in early life.

That question permeates the writing as much as summer suburbs and the tender pathos of being sad and questioning, bored and horny as a teenager and all those same things differently configured as an adult.

In writing, I believe we must acknowledge the limits of our own experiences while keeping our empathy for those of others boundless. We must never write as if we are the default norm, especially if we enjoy privileges of whiteness and affluence, class, cisness or being abled, the list goes on.

Our capacity to do harm by carelessness and unawareness needs constant scrutiny evenif writing characters who do consider themselves the norm and are careless and unaware.

I don’t think I’d thought properly about that when I started TIY but it was at the forefront of my mind by the time I finished and I handed some of that to Peach.

Leslie: Can you tell the story of your own mental health experiences, both in life and in connection with your BBC Radio Three essay The pleasure of forgetting and your BBC Scotland documentary podcast We Have Names For People Like You?

Rose: I am close to the end of a PhD in creative writing which explores The Adamson Collection and the lives of those who created the work in the art therapy studio at Netherne hospital while compelled to live there.

So I’m relentlessly thinking about responsibility and ethics and the othering of people with mental illness. About all the kinds of love and sex and neurodiversity and human suffering which were once framed as disease and the lives which were destroyed by that.

Almost everything which has allowed me to survive my bouts of mental illness has come about through unearned privilege and it is of utmost importance to acknowledge that; secure housing, money to pay for the private therapy which has, without a shred of exaggeration saved my life.

Being educated and articulate enough to ask to have my needs met. Having enough to eat, not being cold, not meeting hate and discrimination daily from every structure of society. All of that has eased my path immeasurably and I don’t deserve it any more or less than any other human being.

Anyway, that it part of why I make work around mental illness. I do it in the hope of making people feel less alone; seen and heard and understood.

Often, I have felt lonely; unheard, unseen and misunderstood and much human pain comes from all the ways in which life and people and systems can make us feel that.

I hope that people who hold mental illness as something to fear and ridicule, even if to try to insulate themselves from the possibility that it could happen to them, might have their prejudices challenged or empathy increased by what I do.

I have been very ill before; I have been very well before. I’ve been medicated and unmedicated I expect to live the rest of my life moving up and down that spectrum, sometimes under my own agency, sometimes without the ability to determine the direction of travel. Sometimes caused by circumstance, sometimes by an unknowable accretion of forces in the body-mind.

The future is uncertain and unseeable and I live by the mantra: I would like to do the most I can with the best I feel and that’s how I manage.

Sadly, the problem is that if you are striving to evolve your thinking, to complicate your understanding of mental illness now, or in the past, by the time you place your work on the subject into the public realm, you already find bits of it half-baked; underthought or reductive.

That can make it difficult not to shit on the hard work and desperate desire within it to care and be careful.

I think one of the most important things is never to be defensive about where it might have been better and how it might be next time.

Leslie: Something happens to our past as we re-represent it through different expressive mediums. What has been your own experience of ‘rewriting your own past’. What have you discovered in the process of doing this, and how has it changed the person you are today?

Rose: Memory is by nature as profoundly unstable as much as old nitrate film. As prone to combustion and decomposition.

It’s important to know that in memories, we’re not butterflies pinned to card, but flitting from the centre to the edge and back again. That regardless, of intention, we re-edit memories each time we retrieve them whether for writing or reverie.

They’re understandably precious to us, containing, as they do, the stories of how and whom we have loved, hurt and been hurt by.

They can bring back, those we have lost, the versions of ourselves and others we miss; wish we’d understood better, been kinder to, or told to fuck right off instead of holding near.

But they are stories. Sometimes a narrative understanding of life is useful. Sometimes it’s a false protection against truths which will one day catch up with us regardless of how desperately we attempt to outrun them. I find it very freeing to allow that we’re all unreliable narrators of our own experiences.

To fleetingly return to the question of the therapy I have had, there has been much useful and consoling reframing and rewriting of my memories through that. Enhanced understanding of self and others, retrospective restoration of care where it was lacking at the time.

And in the wider world, I think to bring new context to any history, whether personal or political, local or global, is wonderful and necessary. I abhor the idea of being resistant to new insights; they increase rather than limit and it is nearly always ugly adherence to existing power structures which drive the rejection of them.

We mustn’t be afraid to change ourselves or to allow others the change they most desire and need.

Some moments in life are like those shape sorting toys for little children; no one should have to keep clashing their circle against the square in the hope of forcing it through.

Each of us must decide whether the best solution for our authentic self is to find the shape of the space we can comfortably travel though or to alter our shape to fit the one before us.

Like I said earlier, I am almost always wondering and writing about the extent to which change is possible and the reader almost always encounters my characters in the predicament I describe above.

I think in writing I have met myself and my life aslant and some of the most meaningful and moving responses I have received to my work involve others having the same experience in reading it.

Next week I interview Mulumehoderwa Balangalizi Jean Peter, founder and CEO at the Unity for Sustainable Development Centre in the Nakivale refugee settlement in Uganda.

ABOUT LESLIE TATE’S BOOKS:

Part 2 of my interview with Mark Statman looks closely at Mark’s Latin American poetic influences, his life in Mexico and ends with an extract

I interviewed international poet and translator Mark Statman about Volverse/Volver, his 14th published collection. Mark, who has won national arts awards, is Emeritus Professor of Literary

I interviewed Lisa Dart, finalist in the Grolier, Aesthetica and Troubadour Poetry Prizes and author of The Linguistics of Light (poems, Salt, 2008), Fathom (prose

I interviewed writer Julia Lee Barclay-Morton about her experience of autism. Julia began as an experimental dramatist in New York, moving to the UK to

I interviewed Gillean McDougall from Glasgow, who edited the collaborative projects Honest Error (on Charles Rennie Mackintosh and his wife Margaret Macdonald) and Writing the

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |