SARAH ROSS-THOMPSON AND THE ART OF COLLAGRAPHED PRINTS

I interviewed artist Sarah Ross-Thompson whose exceptional Collagraphed prints use fabrics, lichen, porridge and string to create images of the dramatic Scottish Highlands where she

I interviewed ex-broadcaster and poet Polly Oliver about oral and visual poetry, her compositional methods, and learning the Welsh language. Polly says, “I absolutely love how social media has levelled the playing field and shredded the rule book when it comes to poetry!”

Leslie: Tell us about being a radio journalist. What did you cover, on what stations and how? What are the unwritten ‘dos’ and ‘don’ts’ of radio presenting?

Polly: The first radio news job I took after completing a post Graduate Diploma in Broadcast Journalism took me back to South Wales where I had studied for my English literature degree.

That first station was until recently called The Wave and its sister station Swansea Sound, but its brand has now been absorbed into a UK wide network.

That started a love affair with South Wales which continued long after I fell out of love with journalism twice (for long-winded philosophical reasons as well as a massive practical one, namely money).

In the time that I went from my post-Grad into my first few jobs across stations in South Wales, both commercial and BBC, the world of news changed enormously. That’s a whole other article for now, covering the dominance of social media, AI, misinformation, disengagement from traditional politics and people’s fast-disappearing attention spans.

But you still have to find the story, get the facts right, make sure you’re not breaching any legals or reporting restrictions, and present it in a manner that is both authoritative and approachable.

And yet, “Plus ca change”. The more things change they more they do indeed stay the same. One of my first big news stories was covering the massive job losses at the steelworks at Llanwern, at that point owned by Corus. Capturing reaction with a minidisc recorder, driving back to the studio, writing a bulletin in time for a live read at the top of the hour.

Here we are a couple of decades later; journos can pretty much do everything from capturing reaction, sending voicers, updating socials and creating a video from their smartphones. But the stories are eerie echoes of previous ones.

This time it is TATA obliterating the epicentre of the economy and even regional identity to a certain extent in Neath Port Talbot and beyond by shutting down the production of virgin steel at Port Talbot.

Those iconic towers standing guard over Swansea Bay, billowing smoke back over the M4 have always marked the gateway to home since I came here to live, love and work.

Leslie: How does the mindset of radio journalist/communications officer differ from being a poet? What are the differences between how words are used in these two fields?

Polly: When I started my journalism course one of the tutors asked the students, “Which of you have done an English Literature degree?”

To those of us who raised a hand he said, “You’re the ones who usually find it hardest.”

He meant we have a tendency to “show” rather than “tell” in our writing, and while storytelling for journalists does need creativity, you also need to balance that with getting to the point and hitting the who, what, where, why and how fast and without ambiguity!

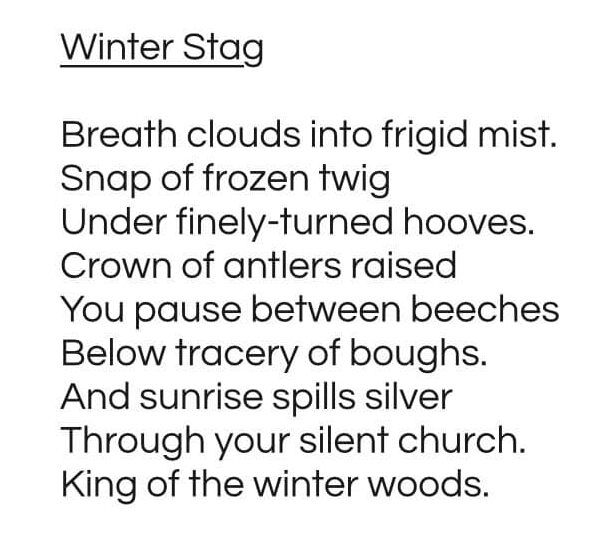

Poetry by contrast is a pretty impressionistic, multi-layered affair, using far subtler ways of delivering a very personal interpretation of the fleeting or timeless experience. A beautifully crafted image or metaphor, a subtle shift of pace or an impactful comma is not going to hit the bill in a two-minute bulletin!

Leslie: Tell us about what you get from the textures of spoken language at open mics and as ‘an exile in another land’ and through Spillwords. How does the Welsh language differ from English?

Polly: I’ve lived here for over two decades and until recently, I learned little more than a few obvious phrases; diolch yn fawr, shwmae, da iawn, etc, although my Welsh place name pronunciation was good early on due to working in radio news and having to be credible on-air to a local audience.

Through the social landlord I currently work for I began to learn the Welsh of South Wales last year; something that was on my to-do list for ages. I have just taken my first exam – Mynediad/entry level. I won’t found out if I have passed until later in the year, but passing was secondary to just getting familiar with the language.

I think being a wordsmith naturally makes you interested in languages. I like the sounds of syllables and find myself tracing the links between words in different languages. An obvious example is the place name component words, which are so close between Cornish, Breton and Welsh. It sounds a bit far-fetched, but those links lead back like a golden thread to ancient ancestors with their own beliefs and priorities which still echo in our own times.

Growing up in Cornwall/Kernow, spending holidays in places in Brittany/Breizh that were twinned with our local villages and towns, and having a Welsh father before moving here myself, meant I got used to seeing the common roots early on.

And there is probably no more poetic language than Welsh! Yes of course the language gave rise to two of the most poetry-tastic words ever; hwyl (roughly pronounced “hoil”) and hiraeth (roughly pronounced “here-eye-th”). But even simply saying “sorry” is richer: Mae’n ddrwg gyda fi, translates as “It’s bad with me.”

The nuances of people’s relationship with Welsh, and even the politics of it is also interesting. And like so much poetry, this kind of nuance is also tied to politics, history class. I think its wrong that people from working class areas in the south where Welsh isn’t spoken so widely can feel judged as somehow “lesser Welsh” for not being able to speak the language.

Welsh history springs from a Bardic tradition of sharing poems and songs by word of mouth and perhaps that gives a resonance to open mics I’ve been to here. But I firmly believe all poems should be read aloud anyway. How else to capture the subtle songs hiding in the lines, the internal rhymes, the assonance or alliteration?

Hearing a poem of experience delivered “in colour”, for example with an accent, or the creak of getting older, adds so much more.

Leslie: What are your personal habits/quirky methods/patterns during the writing process? What are you looking for when you edit your work and how do you change it?

Polly: I’ve struggled with focus and time management all my life. I was the child told off for “daydreaming” in class, and I could do stupid things on impulse.

Sometimes I’m virtually vomiting poems, picking lines from my footfalls as I walk and pulling threads from the chatter in my head; at other times I hate poetry, think I’m dreadful at it and won’t go near a notebook for weeks!

Developing positive productivity habits and consistency is hard for me and I have a tendency to get really overwhelmed and discouraged.

I can’t really describe how a poem “arrives”. It might start with an image or a phrase picked up in a shop or café which I build on. It might just be the memory of a dream or a sudden “zooming in” of awareness of the natural environment.

Although I’m not a fan of social media in some ways, probably the thing that I have found most consistently helpful, as well as warm and inspiring, are the prompts and competitions on platforms like Twitter such as “Top Tweet Tuesday” by Black Bough Poetry.

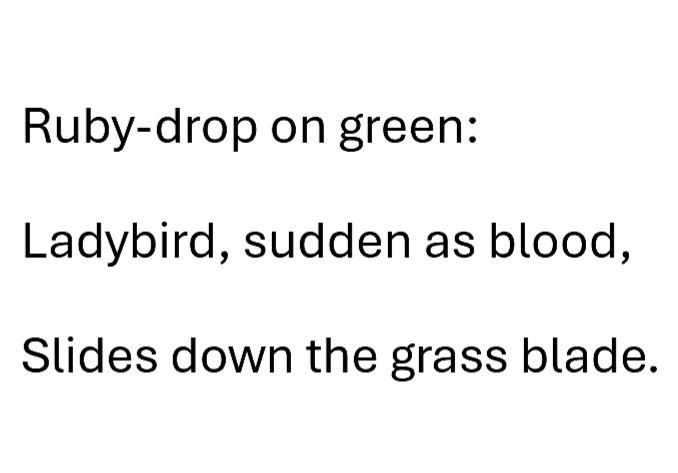

This has gone from a weekly imagistic poetry share to a fantastic global poetry community and has given rise to some beautiful collections. I like my poetry short and imagistic so this suits me, but there are so many writing prompts and challenges out there on all platforms.

Ekphrastic challenges, for example by poet and poetry champion Paul Brookes, also kick off the creative process.

Being able to share poetry as reels or on TikTok has given rise to an explosion of creativity and genre-crossing, as well as exponentially fuelling our options for tapping into the performance elements and authentic voice of poetry and its creators.

I absolutely love how social media has levelled the playing field and shredded the rule book when it comes to poetry!

The dread E word (editing!) is something a dopamine-driven person like me wants to dodge as much as possible! If I’ve had a flurry of focus, its channelled at getting that creative piece down on paper, out in the world and flying around as fast as possible! Having to hammer out the finer details and smooth the edges with editing is a chore, but one I try to approach with the cold brutality of an executioner.

Leslie: Can you describe, please, the subjective experience of a piece of your writing ‘growing up’ and going out into the world independent of you. What have you learned through hindsight, looking back at your earlier writing?

Polly: Here’s the magic part I suppose, and the aspect of writing a poem that runs counter to how poems are traditionally “analysed” and “studied”.

Not one poem will be read or understood or experienced in the same way by different people.

For one person sitting at the back of an open mic session in a market town having just experienced an emotional break-up, an image or phrase might have more impact, might even cause the prick of a fresh bout of tears.

For another, curled up with a book in front of a fire, the clarity and originality of an image in the same poem might cause a little smile of appreciation… you get the picture.

I would bet that most of us feel writing as somehow coming from “outside” ourselves; anyway, I know I do. We take control of a poem briefly while we shape the lines. We straighten its tie and wipe a smudge from its cheek when we edit it.

But once it is being read inside a stranger’s head or spoken into a mic, its not really ours anymore. The reader has no idea about us and what we brought to that poem. They don’t care about our histories and hang-ups, how we look and how we are feeling right now. That’s humbling and liberating.

People might want to connect emotion or experience in a poem, and it could well be the catalyst for beginning to write. But people come to a piece with their own baggage, perceptions and too much writer wallowing between the words makes the poem heavy and flightless.

On the flip side of that I also have a bit of an issue with poetry trying to be too clever and coming across as completely unintelligible. Poetry has a bit of a PR problem anyway and a lot of that comes from readers being left with the sense of someone making a joke that only those in a writing clique will get.

It’s a line we walk between clunking or mawkish and trying to be too smart!

Next week, I interview Jane Burn who won the Michael Marks Environmental Poet of the Year.

ABOUT LESLIE TATE’S BOOKS:

I interviewed artist Sarah Ross-Thompson whose exceptional Collagraphed prints use fabrics, lichen, porridge and string to create images of the dramatic Scottish Highlands where she

Part 2 of my interview with Mark Statman looks closely at Mark’s Latin American poetic influences, his life in Mexico and ends with an extract

I interviewed international poet and translator Mark Statman about Volverse/Volver, his 14th published collection. Mark, who has won national arts awards, is Emeritus Professor of Literary

I interviewed Lisa Dart, finalist in the Grolier, Aesthetica and Troubadour Poetry Prizes and author of The Linguistics of Light (poems, Salt, 2008), Fathom (prose

I interviewed writer Julia Lee Barclay-Morton about her experience of autism. Julia began as an experimental dramatist in New York, moving to the UK to

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |