SARAH ROSS-THOMPSON AND THE ART OF COLLAGRAPHED PRINTS

I interviewed artist Sarah Ross-Thompson whose exceptional Collagraphed prints use fabrics, lichen, porridge and string to create images of the dramatic Scottish Highlands where she

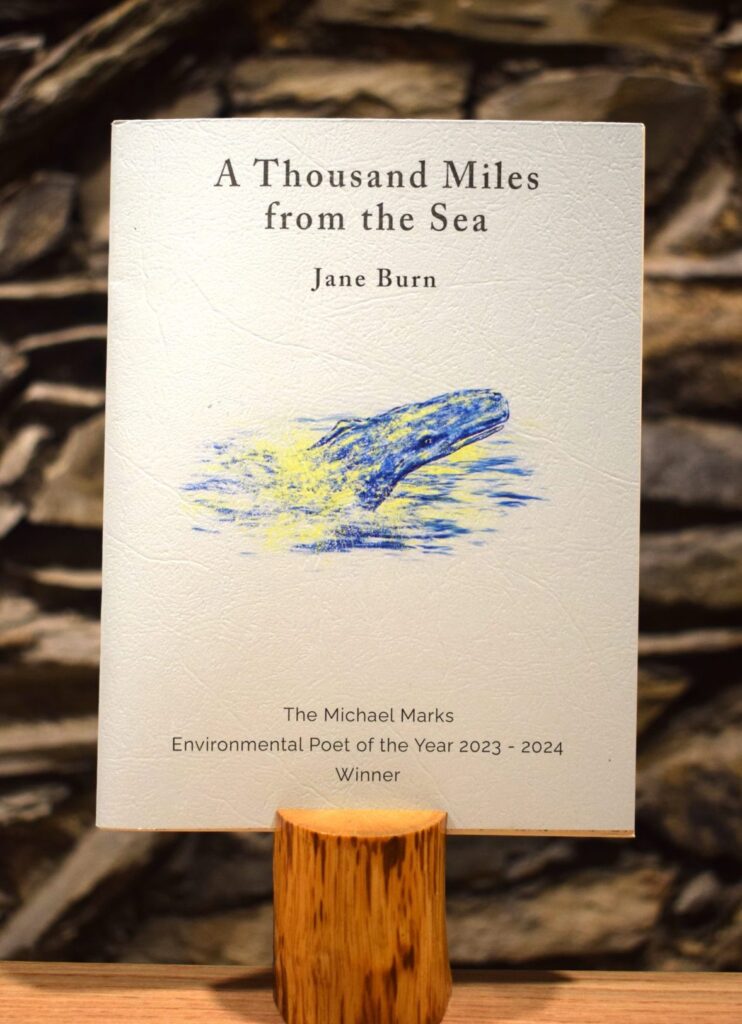

I interviewed poet & artist Jane Burn who won the Michael Marks Environmental Poet of the Year 2023-24 with A Thousand Miles from the Sea. Jane, who is prolific multi-published poet, talks about autism, her compositional methods and her deep identification with animals and the natural world.

Leslie: Tell us about Un/Natural. How do you treat neurodivergence in your work and how has being a working-class woman impacted on your identity and day-to-day experience?

Jane: Neurodiversity? I don’t think I do treat it. I am it and it is me. Everything I have ever written involves me, a neurodivergent person, at its core, in the same way that I consider everything I have written using our home-made solar power to be an eco-poem, whether it be about nature or not. Every poem I have written is a working-class poem because I am a working-class person, no matter what the poem’s content or theme. Every poem I have written is a poem with my autism in its heart, because I am a person with autism. I cannot separate from myself. Every poem I have written is written by a writer with a disability, because I am a person with a disability. Of course, as I have grown in courage and experience, some of my poems have begun to make more direct references to class, autism, disability or the environment, but to me, no matter what the subject, every poem includes all that I am, all that I have experienced, all that I believe in, all that makes me me. Poems and the self are, even in the most subtle ways, inseparable.

What I have done is grow in courage when it comes to referencing my neurodivergence. Eleven years ago, I didn’t know a single poet. I didn’t know poetry communities existed. Eleven years ago, I saw an advert for a poetry event in a local library, and I decided to go. Now I know hundreds and hundreds of poets and I have read hundreds and hundreds of poems. Through meeting these people and their poems, I have been able to extend my knowledge of the myriad forms, structures and themes of poetry. The courage of other poets has helped me find courage of my own. I learned that it was OK to write honestly about physical and mental health, disability, neurodiversity, trauma, sexuality, class and discrimination. I found the permission and encouragement I needed to develop and use my voice. Five years ago, I began my NHS journey to my autism diagnosis. This has freed me to write more directly about being a person with autism. Before the diagnosis, I worried I was wrong, that I would be seen as a fraud, that I had no right to include it in my work. I am currently experiencing similar worries as I come to terms with worsening physical disability, and its place in my thoughts and writing, but I am addressing this internalised ableism word by precious word.

It has taken much work (and many first drafts) to channel the raw feelings of sadness and anger I have experienced (and still experience) at the inequality and discrimination I have suffered into a more controlled, effective, articulate and confident means of expression. I have used the edge of the emotional blade to hone myself into a better writer. It has taken a lot of work to recognise and value myself as an equal. I cannot control how others see me. I am a work in progress. It takes time to recover from experiences of ableism and classism, and to find a means to voice them, while at the same time trying to write the best possible poems I can. It is an endless balancing act.

Leslie: How has poetry helped you to come to terms with demanding or challenging experiences?

Jane: As the years have passed, I have read and written as much as possible. Daily writing at first was a discipline I tried to encourage myself in. It fast became a necessity. Is it a cliché to say that every day, in some way, writing saves my life? Writing is a conversation with life, with trauma, grief and memory, with the past, present and future. Writing is a conversation with history, myth, the many artistic disciplines, with science and nature, with the mind, body and soul. When I could have been lonely, I am fulfilled. When I could have been lost, I am occupied. Since beginning to write, I have never been short of someone to talk to, never been short of a friend. The page cannot hurt, insult or belittle me. The page does not judge what I think, say or feel. The page is never a failure. Nor does the page reject me – every letter written there is a win. A poem is a processing of an aspect of life. You never have to show it to anyone unless you want to. A poem is where you map the private self, where you translate experiences into understanding, where you simply unload and feel better for having done so. I have rebuilt myself many times through them. Poems are a wonderful vessel for the emotions. Poems hold our joys and passions as well as our pain – it is important to remember that

Leslie: Tell us about the typical beginning, growth and development of a short or medium-length poem.

Jane: I don’t think that I have a typical way of developing a poem. In fact, I know that I don’t.

Sometimes, I have the experience of a poem tumbling out of me, almost fully formed. It may feel as if the poem has come from nowhere, but I know that this is not the case, even though it might seem so at the time. I believe that we carry an infinite supply of material around in our subconscious – it melds and morphs with our thoughts, with things we are currently researching, with things we are currently thinking or experiencing, with memory, with workshop prompts. All this information swirls around our minds, then suddenly, the right combinations of thought collide. Like two mental ley lines crossing, we suddenly find a poem sparks into life. There must be some magic formula for poems like these –

subconscious information stockpiles + current circumstances = instant poem.

We have still put years of work into this poem – we just don’t recognise the endless harvestings of inspiration that have brought us to these fleeting moments. These poems seem, for me, to be most common when attending a workshop – the speed one must think and work at when attending these is particularly good at activating the subconscious, from either panic or excitement. One doesn’t have the time to luxuriate in thought, so fight or flight comes into play.

Sometimes my poems develop out of a period of intense research, when I have become fascinated with a particular topic. In these circumstances, I have more of a sense of a poem being built line by line from my learning. These poems are the opposite from the above ‘instant poems’. They come from direct and current hard work, from reams of careful notes, from a lot of identifiable hard work. One might be in this area when exploring the themes of a collection, of for a long poem, or a series. These poems seem, for me, to be most common when attending a workshop – the speed one must think and work at when attending these is particularly good at activating the subconscious, from either panic or excitement. One doesn’t have the time to luxuriate in thought, so fight or flight comes into play.

Sometimes my poems are reactions to a set of circumstances – a news item, something that has just happened to me, something I have just witnessed. These poems are a mid-point between the instant-poem and the hard graft poem. Immediate notes must be made while the experience is fresh in my mind. Emotions and reactions are examined and documented. Examples of poems in this area might include responses to politics, artworks and eavesdropping in a café, for example.

Of course, the instant poem, the hard graft poem and the reaction poem are never quite independent of one another. They all lean on one another for background support and information. Each method of writing finds intersections with others – an instant poem might be a good beginning but need hard graft to help it find its true body, as might a reaction poem. The hard graft poem might need reaction to give it current relevancy. One way of working tends to inspire another. For me, there’s no one rule.

I must also mention the experimental poem. Often, I begin writing one way and my instinct for the poem begs me to become creative, or move into asemic or hybrid writing, or use shape and space. There are hints and whispers, signs and stories everywhere in poetry. Remaining open to them at all times is key for me.

Each poem must take its own unique time to settle during the editing process (and is that process ever truly complete?). Some poems seem to need more editing than others. Some end up never working at all. Some need a day to be tweaked. Some require nursing through the years. Your poems alter and grow as you do. What made sense three years ago might be a totally different creature today. Do we return to the person we once were and change them, or do we accept our past poetry selves? Is it right to edit ourselves out? An interesting thought.

This answer might come across as deliberately oblique (I hope not). Every poem is unique and after I have written one, I always have the same thought – well, I never expected to write that!

Leslie: Tell us about your animal and natural world poetry. What do you bring to writing about myths and folklore that represents your own unique take on the subject? Is there a distinct style and voice you adopt for the subject? What themes/creatures fascinate you – and why them?

Jane: In myth and folklore, as in nature and the animal kingdom, we can discover many ways to conceal, reveal and translate the self. We are living through strange, uncertain, difficult times. Our voices can sometimes feel silenced or lost. Sometimes we don’t know how to begin expressing ourselves. A direct approach to writing our lives can often seem too harsh, too exposing, too problematic. Speaking our truth through the voice of ‘others’ can often slant us into what we might struggle to say or can provide new ways of speaking. Sometimes, the voice of another can simply help us express our own joy in the world around us.

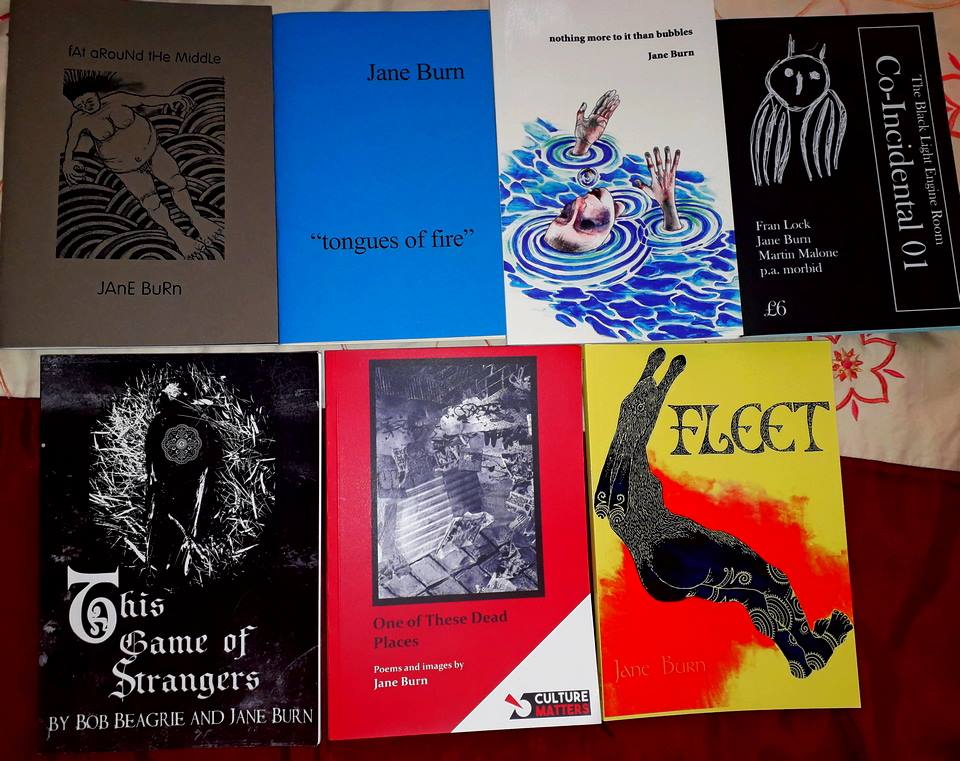

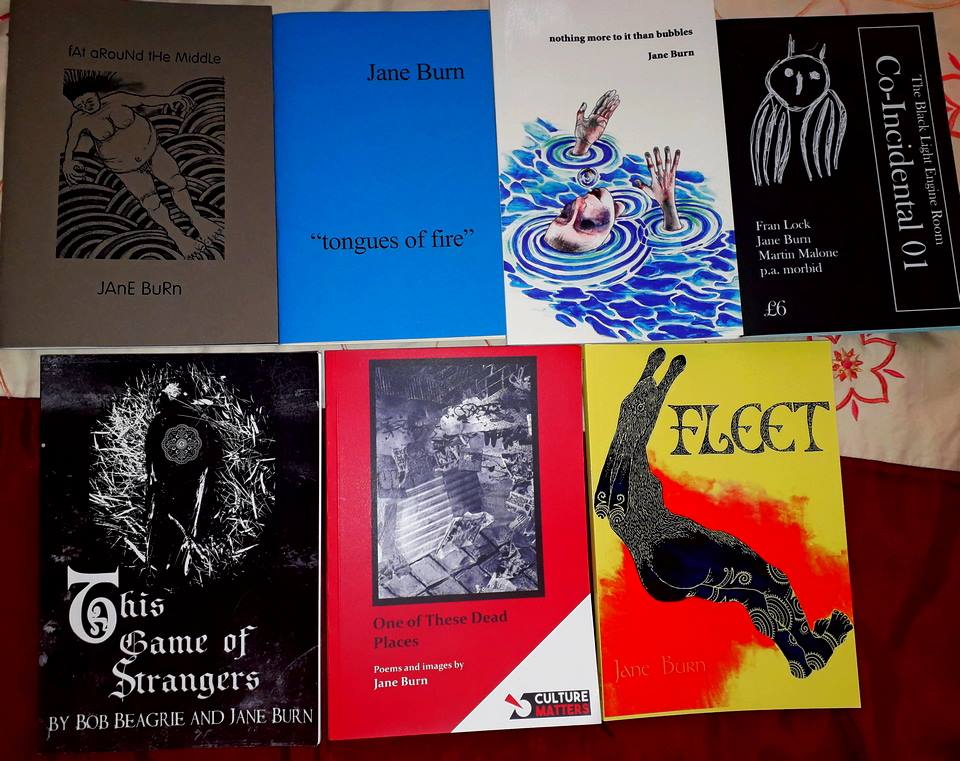

I have borrowed the bodies of many creatures – here are a few examples from some of my books. In my Indigo Dreams collections, Yan Tan Tether and nothing more to it than bubbles, I have been a mermaid, a fairy, a froghopper, a mythological badger, a Swaledale Ewe and a slug to name a few. In my book-length poem Fleet, I was three generations of hare witches. In my Nine Arches collection Be Feared, I have been most of the cast of the Snow Queen story, Thumbelina and Sleeping Beauty. In my upcoming Nine Arches collection The Apothecary of Flight, there are moments when I am a horse, a fish and a bear, or a bird. How we dream of song and flight! They have provided wonderful, safe walls for me to ‘hide’ behind. We can also find parallels between another character’s life and our own. Just as life can be, mythology is plentiful with tales of suffering, abuse and broken hearts – of journeys, magic and love. We can lean on those stories to help us share our own.

When I use the voice of a mythological character or a creature, I can retell situations from my life from altered points of view. If, for example, I choose to be a horse, how do I now respond to what is happening around me? How do I tell it? What has happened to my words? How do my priorities change? Am I afraid? Am I strong? How do I physically move in this new landscape? I can let myself move away from human characteristics as much as I can. Of course, I am a human being and nothing can change that – I can never truly know what it is to be a horse or a hare, or any other creature, but I do know that standing outside of ourselves can lead to some thrilling and unexpected writing.

I try to help this different voice along with research of both the character or creature and of the locations they occupied. This allows for the introduction of terminology, dialect or different languages, as well as information that helps imagine new landscapes, weatherscapes and fairy tale settings. All of these can produce great poetic material, which can help guide the writing process.

Why a horse? Because they possess the whole universe in just one of their eyes. Why a bear? Because I am clumsy and lumbering. Why a fish? Because I often feel out of air, or out of the water. Why any creature? There is something of us to be found in all of them – in their bodies or behaviours. We like to dream of possessing an ounce of their magic.

ABOUT LESLIE TATE’S BOOKS:

I interviewed artist Sarah Ross-Thompson whose exceptional Collagraphed prints use fabrics, lichen, porridge and string to create images of the dramatic Scottish Highlands where she

Part 2 of my interview with Mark Statman looks closely at Mark’s Latin American poetic influences, his life in Mexico and ends with an extract

I interviewed international poet and translator Mark Statman about Volverse/Volver, his 14th published collection. Mark, who has won national arts awards, is Emeritus Professor of Literary

I interviewed Lisa Dart, finalist in the Grolier, Aesthetica and Troubadour Poetry Prizes and author of The Linguistics of Light (poems, Salt, 2008), Fathom (prose

I interviewed writer Julia Lee Barclay-Morton about her experience of autism. Julia began as an experimental dramatist in New York, moving to the UK to

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

One Response

Thank you for a well-considered and honest response to Leslie’s questions, Jane. I read one of your poems in an anthology and wanted to know more about your writing- this tells me so much about the process of creating poetry that is similar to how poems come to me also. I have never seen this process written down like this and yet- so true! Thank you.