No products in the basket.

LISA DART – SURVIVAL POETRY AND THE VOICES OF EXPERIENCE

I interviewed Lisa Dart, finalist in the Grolier, Aesthetica and Troubadour Poetry Prizes and author of The Linguistics of Light (poems, Salt, 2008), Fathom (prose

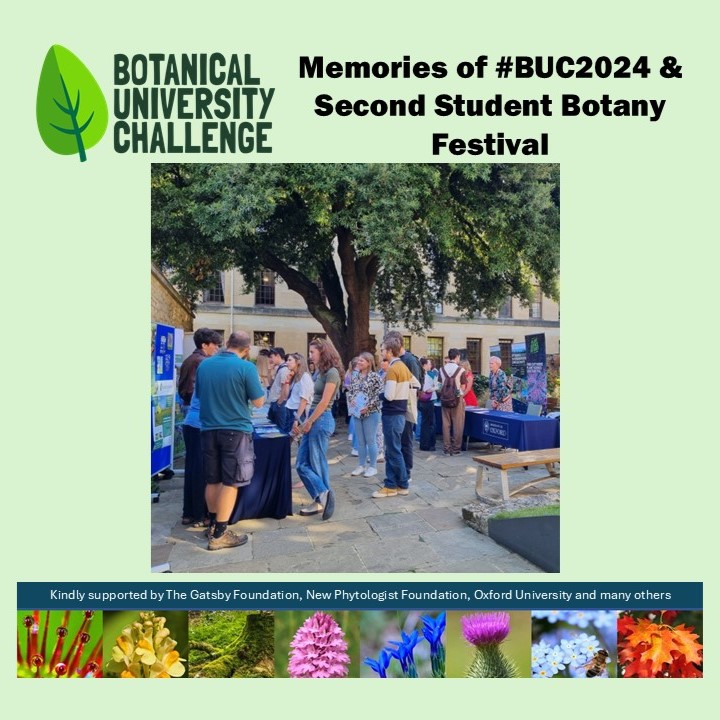

I interviewed botanist Sebastian Stroud about his fascination with urban plants and his research into public awareness of plants. Working in this field, Sebastian’s findings suggest a need to increase our society’s knowledge of plants and their vital role in a healthy ecosystem. To help with this, Sebastian co-runs the Botanical University Challenge, where botanical students compete against each other in a fun, friendly plant-knowledge quiz.

“I think what most attracts me to plants is the way they bring people from all backgrounds together.” – Seb Stroud

Leslie: What led you to become an urban botanist? What sort of things do you do in that job?

Seb: So, my childhood was mostly filled with running around our local woods and parks pretending to be knights, dragons, and other mythical beasts. I think this, combined with my natural curiosity, led me to develop a fascination with the natural world. From here I headed to university to study zoology but soon realised that my career options would ultimately be slightly limited and perhaps a more viable solution was a degree in ecology. Ecology seemed a natural choice.

From here I did a MSc in Biodiversity and Conservation where I really first developed my love of plants. Realising that I actually very much enjoyed learning about plants and how they influenced the environment around them I pursued a PhD in urban ecology, where I really honed by craft. Undertaking research on canals, floating ecosystems, and urban flora really forced me to develop me skills as a botanist.

Rather than calling myself an urban botanist, it is urban areas I call my stomping grounds. You often find strange alien species that have been brought in through various routes. My day job is as a Teaching Fellow at the University of Leeds, where i am able to spend some time doing my three favourite things: teaching about plants, learning about plants, and researching plants!

Leslie: What are the individual plant behaviour stories that have most interested/fascinated/surprised you – why them?

Seb: I do particularly love our native parasitic plants – the mechanisms by which they can influence community composition of grasslands is fascinating. I think what most attracts me to plants is the way they bring people from all backgrounds together.

Leslie: Tell us how you researched the use of plants in cities and what were the standout moments/discoveries from that work.

Seb: My PhD research looks at multiple facets of urban greenspace management. Some of these are applied – for instance, validating the use of floating vegetated ecosystems in canals to improve biodiversity, enhance aesthetic and wellness value, and water quality metrics – whilst others focus on identifying trends in the public’s perception and preferences for vegetation types and the ecosystem services they provide.

One of the published pieces of work I can discuss is our review of vegetation-based ecosystem service delivery in urban landscapes. We reviewed the current literature to identify the current scope of research on urban ecosystem services and found that our valuable urban freshwaters are poorly represented. We also observed a reliance on remote sensing technologies, and many studies tend to focus on ecosystem service provision as a snapshot, rather than considering variation across time.

Leslie: When you studied the fall in plant awareness, how did you gather and assess information? What were the most striking things you discovered?

Seb: We looked at various source, firstly we looked to assess if there had been any other studies looking at these trends, either globally or nationally. In paper (Stroud et al., 2022). We found things such as a Swiss study of several thousand participants aged between eight and 18 that noted people could on average only identify five plants. Analysis of South African educational texts noted the content taught is likely not sufficient to provide a strong knowledge or basic skills in the plant sciences and is subsequently unlikely to encourage positive development of values toward plants. We also found concerning evidence from other work revealing potential threats to indigenous knowledge.

We wanted to base our arguments on some solid data from the UK educational landscape, so we used HESA (Higher Education Statistics Agency). Looking at this data. The number of graduates from general biology programmes in the UK between 2007 and 2019 were approximately 104,895, while those enrolled in plant science and plant biology programmes accounted for less than 0.05% of these students (n = 565). From this we calculated that for every 185 general students of the biological disciplines educated, only a single student of the botanical sciences is produced in the United Kingdom. We drilled further into the dynamics of botanical education across modules in this paper, but our conclusion was that neglecting the importance of plants within education threatens the foundations of industries and professions that rely on this knowledge. Furthermore, this extinction of botanical education creates an existential threat: Without the skills to fully comprehend the scale of and solutions to human-induced global change, how does society combat it?

Leslie: What are you currently busy developing at Edinburgh Botanic Gardens?

Seb: We previously developed a online course that shows how nature-based solutions can enhance the lives of those living in urban environments. The course aims to help answer the question about how we can improve urban areas for both people and wildlife. With almost 85% of the UK’s population living in towns and cities, finding sustainable ways to improve urban spaces is critical. Currently the course is being refreshed but we hope to have it up and running again soon. The course was also part of a research project assessing how effective online learning is in this subject area and we are still crunching the really interesting results.

Leslie: Can you describe a few key moments where you felt passionate about plants?

Seb: I help to organise and run Botanical University Challenge. We bring together students of all stages (from undergraduate to PhD) from related botanical disciplines (Plant Science, Horticulture, Plant Ecology etc) to compete against each other in a fun and friendly quiz style contest. I think I find this to be one of the most rewarding activities about plants! They encompass a huge range of different facets, from social and cultural contexts to their biochemical and morphological toolkits. This brings together a huge range of different disciplines and the diverse people who also share this passion. Learning about plants helps to connect us to our history, culture, and each other.

Next week I interview Paul Nelson, who writes books with his autistic son, Michael.

ABOUT LESLIE TATE’S BOOKS:

I interviewed Lisa Dart, finalist in the Grolier, Aesthetica and Troubadour Poetry Prizes and author of The Linguistics of Light (poems, Salt, 2008), Fathom (prose

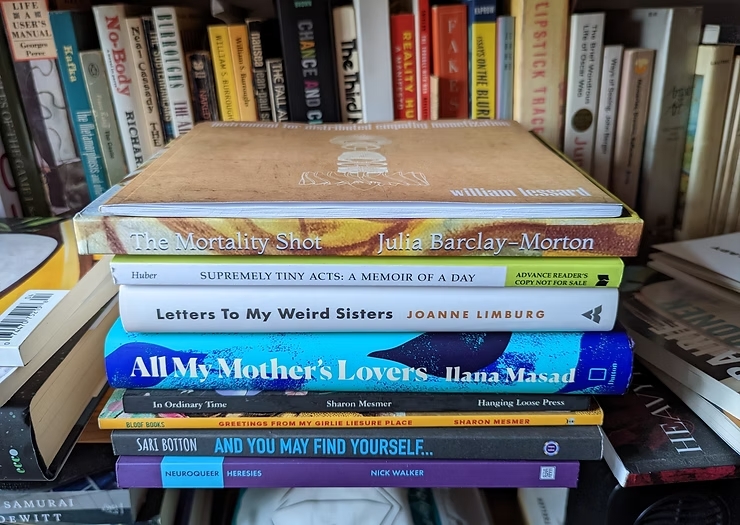

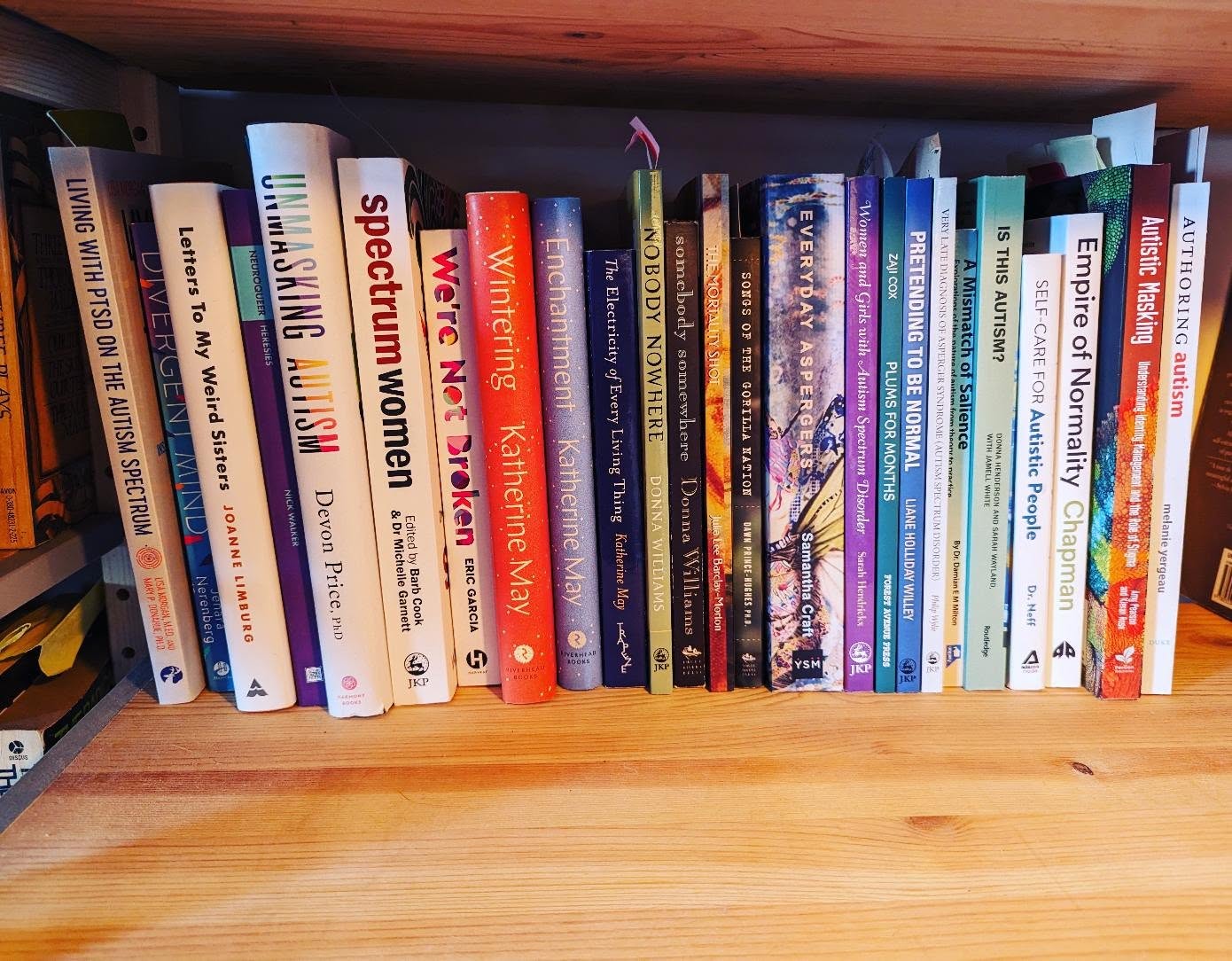

I interviewed writer Julia Lee Barclay-Morton about her experience of autism. Julia began as an experimental dramatist in New York, moving to the UK to

I interviewed Gillean McDougall from Glasgow, who edited the collaborative projects Honest Error (on Charles Rennie Mackintosh and his wife Margaret Macdonald) and Writing the

I interviewed French writer Delphine de Vigan, whose book, No et moi, won the prestigious Prix des libraires. Other books of hers have won a clutch

I interviewed Joanne Limburg whose poetry collection Feminismo was shortlisted for the Forward Prize for Best First Collection; another collection, Paraphernalia, was a Poetry Book Society Recommendation. Joanne

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |