Part 2 MARK STATMAN: MEXICO AND THE POETRY OF GRIEF AND CELEBRATION

Part 2 of my interview with Mark Statman looks closely at Mark’s Latin American poetic influences, his life in Mexico and ends with an extract

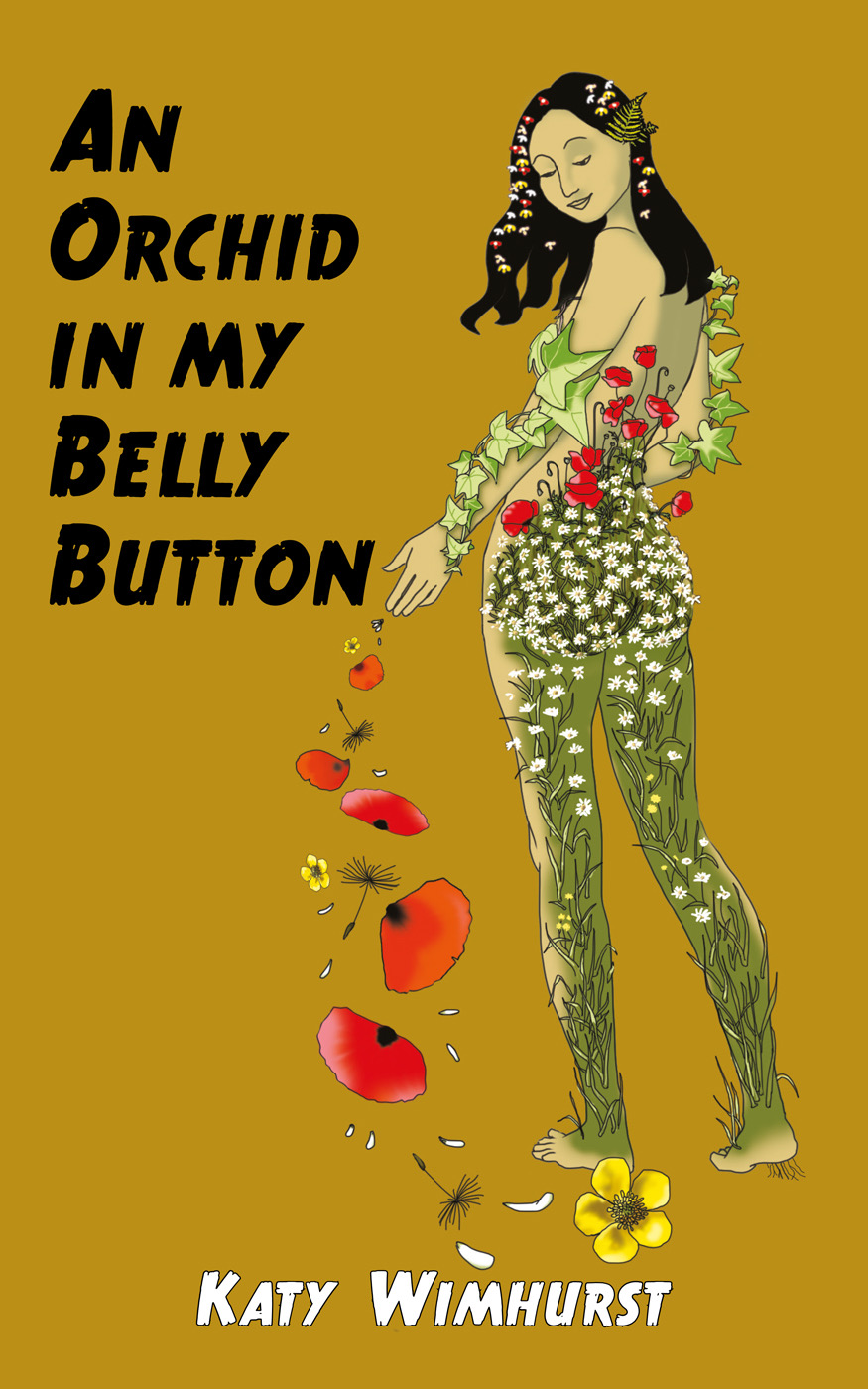

I interviewed Katy Wimhurst about her latest book An Orchid In My Belly Button. Katy writes speculative fiction that: “reflects on ‘what is’ through the lens of ‘what if’.” Katy also describes writing with humour, and the profound effect M.E. has had on her life and writing.

Leslie: You have a new collection of Magic Realist short stories out: An Orchid in my Belly Button. What’s the difference between your Speculative and Sci-Fi or Fantasy Fiction, please?

Katy: An Orchid in My Belly Button features surrealist and dystopian fiction as well as quite a lot of magical realism. I call it all ‘speculative’ because that’s a useful word for fiction with fantastical elements that asks ‘what if’ questions (like, ‘what if a woman started growing orchids from her skin?’ ‘What if a woman had birds in her hair?’ ‘What if a wolf became a Buddhist?’). I use the term ‘speculative’ in the way Margaret Atwood does — stories set in our world (or one very like it) that extrapolate from tendencies in the present rather than using wildly hypothetical ideas like time travel. Most of my stories reflect on ‘what is’ through the lens of ‘what if’. I write dystopian fiction but I don’t write much straight fantasy — when magic appears in my fiction, it is in a grounded, magical realist way, wherein the magic is a more of a playful or literal metaphor than a supernatural force wielded by a Merlin figure. I’m much more inspired by authors like Angela Carter, Franz Kafka, Leone Ross, and Salman Rushdie than J.R.R. Tolkien.

Leslie: How do the stories in your latest collection deal with contemporary problems without becoming a ‘heavy read’?

Katy: Even though I find it hard to turn my gaze away from the terrible state of the world, I strike a balance between the narrative and polemical parts of my writing. Some of the stories in An Orchid in My Belly Button are unrelated to environmental or social issues at all; for example, there is a whimsical piece about a notebook that can see into the future, much to the amusement of its sceptical owner, and another about a snowstorm in a flat. Nevertheless, when I tackle potentially heavy subjects like environmental pollution, I try to create engaging stories with realistic characters who go through emotional arcs. I also use humour and quirky imagery. Humour serves as a wonderful counterpoint in stories that might get too preachy, as does odd imagery. It seems like a lot of authors are tackling social, environmental, and political issues in their fiction these days, so I am hardly alone. But ultimately, stories need to be interesting and fun because if not, why would readers bother with them?

Leslie: How has your fictional style developed from your first two books ‘Snapshots of the Apocalypse’ and ‘Let Them Float’ to this latest collection? What have you learned about writing on the way?

Katy: While many tales in this collection are recent, a few go back more than ten years. Writing, however, is primarily a craft rather than an art form. If you want your writing to be good, you need to learn how to edit well, shaping each draft from an unruly and often crappy initial draft. My skills as an editor have improved over time. I edit extensively; I am not the type of writer who is content to submit after only two or three revisions. I often return to old stories to add a few words here or cut a chunk of text there. As Oscar Wilde quipped about a productive morning’s writing — ‘I took out a comma and then on reflection I put it back’; I relate to that! Being a good editor sometimes means spending time tightening some dialogue, but it can also mean embellishing a particular scene, leaning into it to try to bring out its deeper emotional undercurrent. After leaving a story aside for a time, I read it again with an eye toward trusting my intuition about what works and what doesn’t and making edits based on that. If anything, I have been trying to incorporate more emotion into my fiction and cutting back on snappy dialogue and wit for its own sake.

Leslie: You quote Virginia Woolf as saying that a person relates to, even perceives, the world very differently when sick. How has M.E. shaped your experience as a person and as a writer?

Katy: Had I not fallen ill, I’d never have written fiction — I’d have remained an academic or been a nonfiction writer. So I suppose I can be thankful for my illness in that limited way. Becoming severely ill with a disease like M.E. tosses you into an underworld. The majority of people in the West have experienced losses of various kinds, but I think few can fathom losing almost everything at once — being unable for years on end to watch TV or walk more than a handful of metres, and finding out that there is no cure and some doctors don’t even believe you are ill. Part of my attraction to apocalyptic scenarios in fiction and characters caught up in challenging circumstances stems from that personal experience; writing is an indirect way of processing trauma. Thankfully, my health gradually improved over the years to the point where I could write short fiction (I did, in fact, improve physically too, but I had a physical relapse some years ago). Having a chronic illness also turns you into an ‘other’, and so I tend to write sympathetically about all kinds of others and misfits in my fiction.

Leslie: How do you balance the self-doubting critic with the motivational belief that you’re a great writer?

Katy: I never think I am a great writer like Gabriel García Márquez, but then I don’t think I am a bad writer either. I try to settle for being a ‘good enough’ writer. I do have doubts, every creative does, but I am good at just getting on with writing regardless and not paying much mind to worries about being either great or bad. I don’t think I have a lot of conceit or ego about my work — I’m usually good at taking criticism on the chin and gladly accept edits suggested by editors or publishers. Writing basically comes down to just getting on with it, the nuts and bolts of putting a story down on the page. And learning the craft better, partly through reading other people’s fiction. There is always room for better craft; no one is ever perfected as a writer.

An Orchid in My Belly Button is out in paperback and ebook on 28 February.

Next week I interview Lathalia Song whose art and poetry asks questions inspired by the natural world

ABOUT LESLIE TATE’S BOOKS:

Part 2 of my interview with Mark Statman looks closely at Mark’s Latin American poetic influences, his life in Mexico and ends with an extract

I interviewed international poet and translator Mark Statman about Volverse/Volver, his 14th published collection. Mark, who has won national arts awards, is Emeritus Professor of Literary

I interviewed Lisa Dart, finalist in the Grolier, Aesthetica and Troubadour Poetry Prizes and author of The Linguistics of Light (poems, Salt, 2008), Fathom (prose

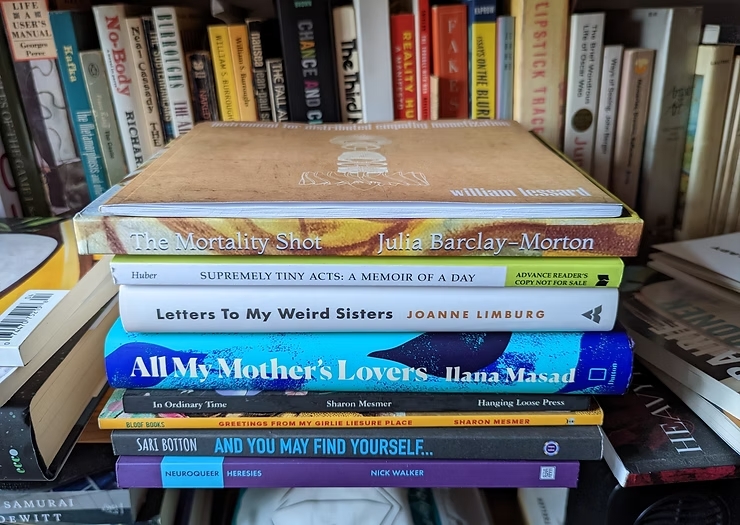

I interviewed writer Julia Lee Barclay-Morton about her experience of autism. Julia began as an experimental dramatist in New York, moving to the UK to

I interviewed Gillean McDougall from Glasgow, who edited the collaborative projects Honest Error (on Charles Rennie Mackintosh and his wife Margaret Macdonald) and Writing the

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |