Part 2 MARK STATMAN: MEXICO AND THE POETRY OF GRIEF AND CELEBRATION

Part 2 of my interview with Mark Statman looks closely at Mark’s Latin American poetic influences, his life in Mexico and ends with an extract

I interviewed writer Julia Lee Barclay-Morton about her experience of autism.

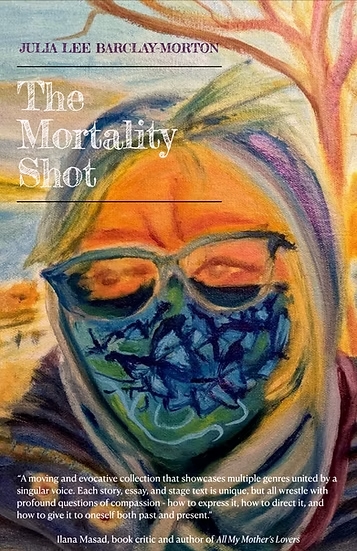

Julia began as an experimental dramatist in New York, moving to the UK to found Apocryphal Theatre and research a PhD in philosophy & theatre. Julia has written a book about her grandmothers, The Amazing True Imaginary Autobiography of Dick and Jani and more about what motivated this book in Women’s Writers, Women’s Books. Her short story White shoe lady won the Nomadic Press Bindle Prize. Julia now teaches her own workshops and coaches writers at university. She is a certified Kripalu yoga teacher, lives in New York, and is the author of The Mortality Shot.

Leslie: Tell us the story of how your autism diagnosis came about. In what ways do you ‘think differently’?

Julia: The story of how my autism diagnosis came about is a long one. As someone diagnosed at 57 this was both a non-linear and unexpected shift in how I framed my life, which has ultimately proved to be profoundly liberating. This is the central subject in my hybrid/researched memoir-in-progress. But the shorter answer is there was a moment with a nurse practitioner friend when she told me after I’d joked for the nth time about being autistic that I did have some of the traits. For many reasons including timing and my long friendship with her, that was the moment that burst through a lifetime of confusion about many seemingly disparate experiences, including knowing I was different somehow and I had a really hard time communicating with people in free-range social situations, how overhead lights made me want to die and no amount of recovery or trauma therapy or yoga or meditation ever made me feel like I had healed from a sense of not-quite-rightness. While all these attempts at healing myself helped, there was always a niggling feeling I was somehow just wrong, a broken toy that could not be fixed. Some part of me had wondered about this for a while, but in an off-stage vestibule behind the dressing rooms—ever present but never quite visible. After my friend said that I had autistic traits, I could see the darkened room and knew I finally held the key to the mystery, which began a process that took over a year that ended with an autism diagnosis in 2021.

I should add I don’t think anyone needs an official diagnosis, but because I’m a writer and was 56-57, I wanted “proof” before writing about such a huge revelation that I was pretty sure most people who knew me would be surprised to hear. Because most people consider autism a series of stereotypical behaviors rather than the internal experience, if you have learned to mask many of the “obvious” tells (which happened for me in adolescence as I desperately tried to find a way “in” to the world) and you have surrounded yourself with other outsiders who are experimental artists and writers (including people who are in recovery from addiction and are neurodivergent whether they know it or not), it’s easy to blend in to the scenery with a convincing dancing seal act. Don’t look at me just all these glittering achievements! Which is surprisingly easy to do. The diagnosis also helped me with my own imposter syndrome. The doctor was quite clear I was autistic, that there was no doubt. Which was both a relief and a surprise, because I thought I was a better masker than it turns out I am.

As to how do I “think differently”—before I try to answer that, I need to add all the caveats anyone writing about being autistic needs to add: I can’t speak for “all autistic people” in the same way no one can speak for all neurotypical people. While Autistics are a tiny minority of the global population, we are still millions of people with varied experiences. Also, if what I say leads you or anyone else who may not consider themselves autistic to say “oh I experience that, too” that doesn’t mean you’re autistic or that I’m not. Of course, there are many autistic experiences that overlap with allistic people’s experiences. A poet friend once said it best: “it’s autistic if it bites.”

OK, so with that out of the way: the way I think is also the way I feel and vice-versa. It’s common for therapists to pathologize the way autistics think-feel as intellectualizing or whatever. Perhaps for a neurotypical person this is true, but for me it’s actually How I Feel. The best phrase to encapsulate this experience is “bodymind”—my feelings and thoughts and sensory experience are all felt senses in my body. The pre-existing words to describe these sensations can be elusive. This has led to the diagnosis (autistic experience is forever being “diagnosed”) of “alexithymia”—which means a lack of understanding of what one is feeling. I have a whole chapter in my memoir disputing this pathologization. Instead of “not knowing” what we feel-think, perhaps there are simply no pre-existing words for our experience. The very language of feeling itself is neurotypical. If we as autistic people (and especially autistic writers) try to use that language, we will always be coming up short. This is why I am embracing what I consider my unmasked autistic voice, and it’s in my stage texts where this unmasked voice emerged decades before my autism diagnosis. M. Remi Yergeau’s writing and thinking in their amazing book Authoring Autism has helped me most with understanding the no-win situation of autistics attempting to function within traditional rhetoric. Joanne Limburg recommended Yergeau when I was asking other autistic writers about what an unmasked autistic voice night be, and I am forever grateful for her referral.

Leslie: How do you teach intuitive writing? How did you discover that capacity in yourself?

Julia: Good question. I discovered it in my own writing and editing before I taught it. I refer to it as “intuitive processing,” which was the name I landed on to describe how I allow the deeper currents to emerge in any thought-out project. In other words, especially when working on oh say a hybrid researched memoir, it’s easy to get caught in the timelines and concepts and Ideas About What I Want to Say. And yes of course that’s all important, but underneath that are deeper currents. Like water, intuition leaks out and can overwhelm any conscious structure or barrier and—in its persistence—create another shape that is more fluid and connected—in the same way that water connects everything on earth. Many autistics feel connected to everything all at once, and this “intuition” I refer to is that which can tap into that sensation. I fear this sounds horribly woo, but it’s the best way I can explain it.

As for teaching intuitive processing, it’s about holding space for free writing and then suggesting ways to shape it (consciously) and then taking the next step of allowing for the flow to perhaps disrupt that shape. The usual model is: free writing then editing to a known form, which is quite linear. The traditional model is drafting is open and flowing and editing is about containment. But what if it’s possible to allow the dance with the editing, too? That’s what I find exciting. It’s slower than working within preexisting structures, but the results are more exciting. As I often say: if you know where you’re going, it isn’t anywhere new.

Leslie: Tell us about the beginning, growth and final development of your book ‘The Mortality Shot’. Why does it use different types/styles of writing, and what do they achieve?

Julia: This book came about when I saw a call out for a hybrid collection of material that held together with a theme. I looked at what I had written over the past few years, including essays, stories and a stage text, and realized they all had to do directly or indirectly with mortality. I proposed the book to this publisher. While they ultimately didn’t publish it, they sent a very kind rejection, and another small press did pick it up. The editor and I worked together to ensure the order of the pieces flowed well, and I added some essays we realized added to the whole. So, I didn’t go into this thinking: gee I’ll write a bunch of stuff about mortality and grief in different styles and put it together, but the collection just evolved that way. From what readers have told me, the various pieces achieve a kind of kaleidoscopic meditation on mortality and grief in which you can dip in and out at various points and see it from different angles. Most of the pieces were written before I knew I was autistic, and three while I was in the diagnostic process, including the stage text. However, autistic writers who have read the book consider it all from an autistic point of view, which is of course true. How could it not be?

Leslie: How have yoga and other meditative disciplines contributed to you as a writer & person?

Julia: That’s such a good question. Meditation saved me life, which sounds really melodramatic, but it did. I sat down to meditate one day in the mid-90s and after 20 minutes sitting on a sofa with coffee and a cigarette (seriously) focused on my breathing, I felt a moment of calm. I did it the next day and the next and the next, and have been meditating daily ever since. This practice of simply sitting with myself in whatever state of bodymind, whether upset or calm, thinking or not, I get a chance to catch up with myself. I can’t bullshit myself for those 20-25 minutes. Over time this practice has led to many profound changes in my life, mostly in the form of people and places and things and ideas about myself falling away that didn’t need to be there anymore. I began a serious writing practice a few years into meditating, for example. The yoga, which came about five years later, added an embodiment I had never experienced before. I had lived neck up until then, and without yoga I could not have done the trauma therapy or gotten to the place where I understood I was autistic. Aspects too of my Kripalu lineage, especially the focus on witness consciousness affected my theater practice as a director and writer, while giving me space to allow the changes in my life and writing that need to happen. I should emphasize all this has happened over decades of practice. It’s not a quick fix. The practice is about more and more acceptance of one’s self and the world and others as they are at a deeper and deeper level. “Acceptance” doesn’t mean you have to Like it. Acceptance means seeing the reality of the situation so you can act accordingly. If a cyclone is about to hit, I need to see and accept it’s a cyclone. If I keep telling myself a rain storm and just sit there like everything’s OK, I’m gonna get hurt. You get the idea.

Leslie: Tell us about your lifelong fascination with water. How has your perspective on life-giving obsessions such as this changed with age?

Julia: This is my favorite question because I just spent a month on my favorite island in Scotland staring at the water (and writing), which led me to read Theory of Water: Nishnaaabe Makes to the Times Ahead by Leanne Betasamosake Simpson. I have discovered while researching my memoir that as an autistic person I am not alone in my fascination with water. Fernand Deligny offered refuge to non-speaking autistic kids in the 1960s-80s in France, letting them just be instead of trying to “fix” them (an idea decades ahead of its time). He noticed the kids were more interested in water than people. I can relate to this sentiment, as someone whose first word was “wawa” and whose first sentence was “I wanna go beach.” Deligny instead of pathologizing their focus instead asked, “How can we make ourselves water in their eyes.” Which I think is gorgeous. Simpson in her book talks about the physical properties of water and the mythological place it holds in her culture. Nibi is the word for water, and the primary property attributed to Nibi is that no matter what is put in its way, it will leak out, or eventually wear down any obstacle. Simpson also writes about how water shifts substances from liquid to cloud to snow to ice to tears…how it’s what connects everything on earth, it’s our blood, our veins, our lungs. I relate to all of this, and from what I know of my own perception—and have read and heard from other autistics—this sense of profound connection with everything is a key feature of autistic experience, whether non-speaking or hyperlexic. It is also what keys me into autistic joy, which I can best summarize as a sense of my own connection to everything to such a degree that nothing can destroy me. Water—especially tidal water—beings me there every time.

Leslie: Why do you write?

Julia: Writing seems perverse especially knowing the impossibility of preexisting language to truly embody the autistic experience—or any experiences that transcend the words we have already assigned—but there is something about the attempt that seems important, especially now, when autistic personhood and value is once again being contested and most research is designed to wipe autistics out of the gene pool.

My best and most surprising writing ideas tend to come when I’m meditating and doing yoga. Or walking alongside tidal water…I wanna go beach.

ABOUT LESLIE TATE’S BOOKS:

Part 2 of my interview with Mark Statman looks closely at Mark’s Latin American poetic influences, his life in Mexico and ends with an extract

I interviewed international poet and translator Mark Statman about Volverse/Volver, his 14th published collection. Mark, who has won national arts awards, is Emeritus Professor of Literary

I interviewed Lisa Dart, finalist in the Grolier, Aesthetica and Troubadour Poetry Prizes and author of The Linguistics of Light (poems, Salt, 2008), Fathom (prose

I interviewed writer Julia Lee Barclay-Morton about her experience of autism. Julia began as an experimental dramatist in New York, moving to the UK to

I interviewed Gillean McDougall from Glasgow, who edited the collaborative projects Honest Error (on Charles Rennie Mackintosh and his wife Margaret Macdonald) and Writing the

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |