SARAH ROSS-THOMPSON AND THE ART OF COLLAGRAPHED PRINTS

I interviewed artist Sarah Ross-Thompson whose exceptional Collagraphed prints use fabrics, lichen, porridge and string to create images of the dramatic Scottish Highlands where she

I interviewed Lisa Dart, finalist in the Grolier, Aesthetica and Troubadour Poetry Prizes and author of The Linguistics of Light (poems, Salt, 2008), Fathom (prose memoir, Free Association Press, 2019), and This Thing of Darkness, an experimental, illustrated book (IPBooks, 2024) which won a British Arts Council Award. Lisa’s forthcoming books are: The Bird You Are and Even So, This Song (Shangana Press, 2025).

Leslie: How did you prepare for writing about trauma in ‘Fathom’? How did you weave together personal experience with generic material? What were the most difficult and easiest aspects of writing it?

Lisa: Preparing for writing about trauma in ‘Fathom’ was a rather unwieldy process. I had read quite a lot of books about trauma and how its effects manifest in the body and in the mind. I had also read quite a lot of fiction, concerned with how writers shape texts, create narrative tension and make meanings. I was interested, too, in inter-textuality. But at the time of actually writing, my mother needed considerable help as she was in her late eighties, living alone and not coping very well. So my ideas for ‘Fathom’ – sections rather than chapters, occasional sentences, sometimes just odd words and memories – were jotted down on scraps of paper or amongst my lists of what I had to do for my mother. Mostly though, it was stored in my head and built up there. It was also difficult to find ways of dealing with parts of my own story for which I had no words, no clear memories. Using the words of others, mostly Sylvia Plath’s, in the last section gave me the intensity, the uncertainty and some certainty too for how to tackle those parts of my story. The stress of caring for my mother took a very significant toll on my back and before my mother went into a care home, I was bed-bound for eight weeks. So with a laptop on a small portable table over my bed, dosed with morphine, I wrote ‘Fathom’.

Leslie: How did ‘Fathom’ lead to ‘This Thing of Darkness’? How does this second book use psychoanalysis, philosophy and art to explore the subject of trauma? What grounds the narrative?

Lisa: Actually, I wrote/made ‘This Thing of Darkness’ before ‘Fathom’ which I will explain in a moment. The narrative of ‘This Thing of Darkness’ is grounded in one sense by Wittgenstein’s ‘On Certainty.’ The memories of trauma I experienced as a very young child were like sharp, but disconnected, splinters in my mind. And, because the mind has protective functions such as forgetfulness and repression, I couldn’t remember with any surety exactly what happened. ‘On Certainty’ provided a series of suggestive philosophical propositions that I used as springboards if you like, to explore my experiences. Wittgenstein’s ‘Philosophical Investigations’ also inform the book, since the book is also an attempt to animate and give an emotional hinterland to the concept of language as a game, with rules and the meanings always changing. I juxtaposed the propositions from ‘On Certainty’ with pictures; text extracts from works on psychoanalysis; and a sort of ‘split’ narrative. A first person narrator tells the story of the character ‘L’, but they are, in fact, the same person. The pages themselves are also colour-coded to try and show different levels of consciousness: the rational, conscious mind through to the deep unconscious one. My intention was to create a hybrid way of making meanings — which seemed necessary because a ‘breakdown’ is a fractured and fracturing experience. However, no-one would publish it because it was such an unusual book and, I think, difficult for some publishers to place in any neat genre. My husband suggested I write something more accessible. So I wrote ‘Fathom,’ which found a publisher and ‘This Thing of Darkness’ lay, literally, in my cupboard’s darkness, given up on. It was twelve years after the creating of ‘This Thing of Darkness’, and after my husband’s death, that a friend encouraged me to try again to find a publisher. ‘This Thing of Darkness’ got accepted by IPBooks. I hope my book’s long but ultimately successful journey encourages many writers to keep trying to place their work.

Leslie: Can you describe the process of writing ekphrastic poetry in relation to one or two specific poems of yours, please?

Lisa: In my first book ‘The Linguistics of Light’ there is a sequence of ekphrastic poems arising out of the work of the American painter Edward Hopper. I have always been drawn to the atmosphere of loneliness in Hopper’s paintings, how he uses light to create it. One of the poems in the Hopper sequence is called ‘Rooms-Sea’ and, in fact, the painting I drew on for the poem is the one I used for the cover of the book. But I didn’t start with the painting. I set out to write about a visit to a cattle farm in Arkansas run single-handily by a woman after her husband died. I was at the farm when it was time to bring the cows down from the fields where they were grazing. She whistled very loudly and I watched the cows come down to the barns at quite a pace, almost running. We then went into the rather bleak farm house, which had a significant air of loneliness. The only intimate thing was a little vase of lilacs on the hearth. She had obviously cut them and put them there. You could smell the scent. I saw it as an assertion of life even though she had been so recently bereaved. Trying to write the poem, I found I couldn’t get to the feelings I needed to convey of loneliness, but also of life continuing. Hopper’s painting of an empty sunlit room that opens straight into the sea carried the feelings I was looking for. When I suddenly remembered the painting, I cut back the poem completely. The cows, the farmhouse, the barns, the whistling had all become extraneous. The woman, the lilacs and the comparison to Hopper’s brilliantly lit, but intensely lonely, empty room, all that was necessary.

Leslie: How did you find the exact language you needed to write about the loss of your husband? What did you learn from each other as poets, thinkers and participants in this world?

Lisa: It was very difficult. My husband died totally unexpectedly. Finding words for the trauma, the unspeakable loss and grief was so difficult, both in life as well as writing. Metaphor, as in one of the poems in Even So, This Song, which ends with ‘the suffocating soil of shock buried me alive’, helped to express for me and, hopefully, for any reader, the overwhelming, unsayable shock and emotion I experienced. Early in the volume, there is also a poem about King Lear and Cordelia, which was another way I found to try and get at all-consuming emotion.

In the poem ’Nomi’s Drawing’ ekphrasis helped. By describing my friend’s drawing and trying to enter her grief at the loss of her own husband, the single words in the last line, ‘Cannot. Cold. Husband. Dead.’ became words for my own experience too.

My husband and I talked poetry, I would say, one way or another, every day. Often writing poems during the day and reading them aloud to each other and talking about them critically in the evening. That, or reading other people’s work and enjoying them. He was very established, both as a poet and thinker, when I met him; I was very much a beginner, having written only one or two poems before knowing him. He was hugely encouraging. So obviously I learnt a lot from him but —— and I like that you included it in your question —— as participants in this world our love for each other opened, I believe, a more tender lyricism in his work: I have a wonderful series of love poems from him for every Valentine’s Day, birthday, Christmas, Easter and in-between. As I became more confident as a writer, I became more experimental and I think he learnt from that. He was particularly interested in eco-poetry and, as you may know, produced an anthology called ‘Earth Songs’ to showcase the wonderful celebration and concern so many poets have for our extraordinary natural world. Reading and talking together about this book informed our own work in direct and indirect ways. More generally, we often discussed what could poems ‘hold’ and ‘explore’ in our complex, technological and challenging world.

Leslie: Why did you experience such a shortage of books and art growing up? Has it, paradoxically, fed your adult passion for all kinds of culture?

Lisa: Neither of my parents were well-educated and came from very culturally impoverished backgrounds. To give you an idea, my mother’s father couldn’t read until he was eleven or twelve and learnt because he taught himself. Both of my parents left school at the age of fourteen and neither engaged in any form of further or higher education, seldom reading anything more than a newspaper. They simply didn’t possess the cultural background to pass on. As you know from my website, remarkably, there was one book of poems in the house along with the couple of other books. But my mother did take us to the local library when we were very young and my passion for reading started and, later, a pulsating desire to engage with other art forms as well. My husband used to talk about culture, all forms of culture, as our collective inheritance. He was very opposed to high art being considered as elitist, seeing the arts as the many rooms in the mansion of the feeling life. Our metaphysical home. Once I started to read avidly, the impoverishment of my home when growing up made me realise I was starved. A starvation that did, indeed, become passion.

ABOUT LESLIE TATE’S BOOKS:

I interviewed artist Sarah Ross-Thompson whose exceptional Collagraphed prints use fabrics, lichen, porridge and string to create images of the dramatic Scottish Highlands where she

Part 2 of my interview with Mark Statman looks closely at Mark’s Latin American poetic influences, his life in Mexico and ends with an extract

I interviewed international poet and translator Mark Statman about Volverse/Volver, his 14th published collection. Mark, who has won national arts awards, is Emeritus Professor of Literary

I interviewed Lisa Dart, finalist in the Grolier, Aesthetica and Troubadour Poetry Prizes and author of The Linguistics of Light (poems, Salt, 2008), Fathom (prose

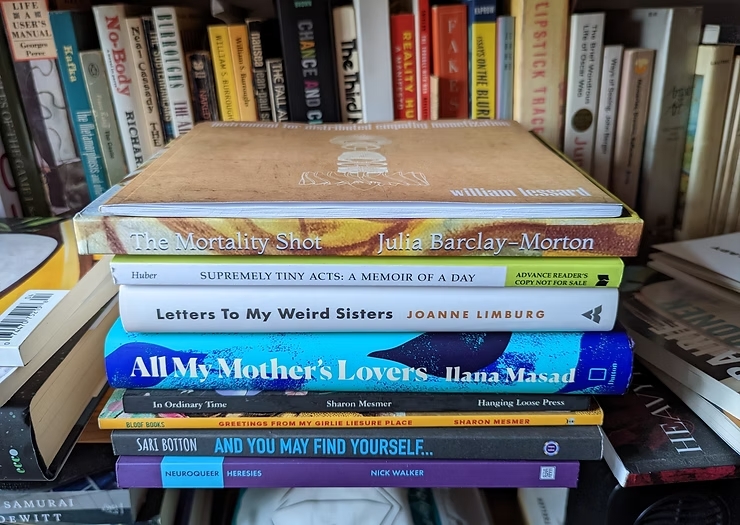

I interviewed writer Julia Lee Barclay-Morton about her experience of autism. Julia began as an experimental dramatist in New York, moving to the UK to

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |