LISA DART – SURVIVAL POETRY AND THE VOICES OF EXPERIENCE

I interviewed Lisa Dart, finalist in the Grolier, Aesthetica and Troubadour Poetry Prizes and author of The Linguistics of Light (poems, Salt, 2008), Fathom (prose

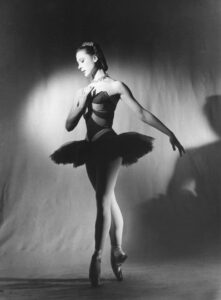

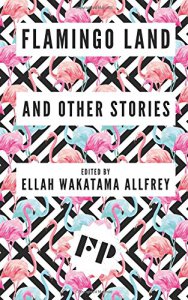

Katie Willis is an author, former ballerina and ME survivor. Recently shortlisted for the Kit de Waal Scholarship, she won second prize in Spread The Word London Short Story Competition, has been successful in the Bristol Short Story Prize, the Puffin Review Fairy Tale Competition and her short story The Passenger has been anthologised in Flamingo Land: And Other Stories. Katie is now editing a novel that was shortlisted for the Brit Writers awards and working on a body of short stories. Katie’s guest blog describes how her powerful creative urge to dance was redirected by illness into writing ‘grown-up fairy tales’.

‘I craved rhythm from the outset but my home was never a musical one. I had songs in my head, from school and from Sunday school, and songs that I was born with and I had no choice but to set them free in dance. The world was an intricate rhythmic playground to me and ballet was my route through the mire. It gave me wings. It left me free to fly if only I worked hard enough. And wings could set me up for life.

When I could no longer dance due to illness, I turned to writing because I had to keep the music alive. It was the only way I knew.

That’s it in a nutshell. That’s the simplicity within the complexity.

But complexity is a many-layered thing. And you have to dig deep to find the bones. As a child I was also a voracious reader and when I wasn’t dancing, I often had my head in a book. That love of literature would later translate into me trying to write mini fairy tales during the endless hours of dance rehearsals.

I’ll begin with a story…

I was lucky enough to be taught by the famous Lithuanian/Russian ballerina, Svetlana Beriosova, at a summer ballet seminar in Ilkley in Yorkshire. She was one of my favourite dancers and one of the reasons I wanted to take up ballet as a career. To watch her dance is to have your heart break twice over. Every single movement she makes tells a story. She draws you in, engages you so you have no choice but to be involved.

She was an older woman when I met her walking into class; quiet, unassuming but never quite blending into the background, always coming alive the moment she demonstrated steps at the barre or from a variation.

My 13 year old self was beyond mesmerised with what I saw. I watched her place an arabesque. The line that she created went on and on. She made a shape in the air that cut into and was part of the space around her. And that one small position was just the start of a bigger story. Something came before it and something would come from it. I could see that so clearly. How did you tell a story without words and how did you tell it well? I was grappling for answers right there in that dance studio. Was it through shape? Through form?

What she did as she taught in that class was so organic. She didn’t just make shapes. She became them.

And when we got to learn the Odette variation from Swan Lake and she began to demonstrate it for us, she didn’t just act out the role. She became it.

But how exactly did she do it? I knew I’d never be able to sleep again until I’d figured it out because I wanted what she had. I needed to be every bit as connected with the audience as she was. I too wanted to engage, to include, to satisfy. I intrinsically understood that engagement was life, that creating and inviting people into your creational space was a potently powerful thing. It was never the kind power that came from elevating yourself above or removing yourself from the masses. No. It was a deeply personal sense of autonomy that involved authentic self-expression.

It was a lot for my teenage self to think over and work on and then Svetlana did something extraordinary which made me love her even more. Swan Lake is a very physically demanding ballet on a professional dancer’s body, let alone on a teenage body and I vividly remember her raising her hand to stop the class, much to the consternation of the pianist, and leading us out single file (we were dancers: we were very disciplined) down to the lake to study the swans. Dropping down on her knees by the water’s edge and humming some kind of swan lullaby that brought the swans gliding across to her, she urged us to watch, to study, to absorb. “Look,” she said sharply. “Absorb and become.”

Of course it was never about pretending to be a swan. It was never about mimicry or a costume that you put on for a limited period of time, it was about truly being a swan.

That was the moment I realised I had to be a professional ballet dancer because there was really nothing else I could do that convincingly and that fondly. I was born to tell stories with every inch of my body and dance offered me ownership of space in a world where I never really felt I belonged.

The audience craves authenticity. I understood that clearly as a 13 year old, even if I couldn’t verbalise it as coherently as I am able to today.

It’s that degree of authenticity that’s as important to me today, as a writer. I invite people into my weirdly wonderful world, where nothing is quite as it seems, and I ask them to pull up a chair and engage in the landscape, in the characters, in the backbone of the story. To do that, I have to give all of myself, let my own heart break a little. There’s no holding back. For that hurts me just as much, if not more than it hurts you, the reader.

That degree of honesty is tough. I seek it out in all the literature I read. I try to figure out how other writers do it. I’m constantly on the lookout for the Svetlana Beriosovas of the literary world. Toni Morrison both delights me and moves me to almost monumental rage, because what she does with the written word is so exquisite, so musical. If I close my eyes when I’ve read a sentence of her work, I can feel the movement, in my bones, in my heart. I’m so broken up by what I read and then I have to fix myself together again. But I like that. That’s powerful literature for me because it engages. It gives as much as it takes.

That’s some kind of exceptional equilibrium.

As a dancer my body was on display to tell a story. No part of me was turned off. I reached out to the audience, with every muscle including my heart. That’s the pinnacle of vulnerability, but it’s truth. And truth speaks loud and clear. It cuts a path through that mire.

I was forced to give up dancing because of illness. Years of daily training produces strong-as-arrow muscles that make perfect lines and shapes in the air. To have that degree of mastery over your body is a gift. And with mastery comes freedom. You realise your body is a magic vessel when all the years of hard work pay off and you jeté or fouetté across the stage and feel for a split-second that you’re flying.

Nothing beats that feeling. It’s exceptional elation. It’s other-worldiness. It’s ultimate freedom.

Illness ripped that freedom from me. It ravaged every muscle I’d trained so hard to strengthen, hone and elongate. At a cellular level, illness battered me. It’s one of the hardest things I’ve dealt with and I still deal with it today. I cannot express in words how it feels to go from having exquisite mastery over every muscle in your body to having mastery over none. It’s like losing your home, your country and your personal identity all rolled into one.

However, I strongly believe in muscle memory. I believe that every day-to-day and every life-changing experience, every dance step ever learned, is stored in the body, deep within muscle tissue. That’s a hauntingly beautiful thing. It’s both incarceration and a way out because nothing ever leaves you but it can be transformed.

That transformation became my salvation. That’s when words replaced movement. That’s when I found I could continue living because the rhythm remained, albeit in a slightly truncated form.

It’s very true there was some inchoate space, some ice-cold stillness after the dancing stopped and before the words came but I can’t dwell on that time because it hurts too much. It’s the worst shade of grey.

I tried to write my way out of illness. I wrote what I describe as grown-up fairy tales (although someone who recently read my work actually described them as more surreal than fairy tale, more post-modern parable). It’s nice to have someone attempt to fit you neatly inside a genre. I’ve always struggled with that!

I wrote to continue living with illness. I wrote to edge out the pain. I wrote over and around the fact that ME, the illness that I live with, currently has no cure. To this day I try to be strength in semi-delirium. Some days stuck in my bed, unable to move, I create my own world, my own kingdom. The discipline, the resilience every dancer learns from that first day of class, has stood me in good stead. There’s beauty in the fact that at my most ill, I have no critical voice. With my temperature sky-rocketing and the room spinning around me, I have no sense of gravity (just a muscle memory of it) no sense of rationality. I heave myself into the worlds I create. I willingly hang out there because it’s infinitely preferable to the murky blackness of illness.

What is night and what is day? Illness often screws with my sleep pattern, my characters start pushing into my dreams. A while back I turned to meditation, mostly to help with the pain, but also to ground myself and to give my brain some free time and for the most part it’s working.

I began with the novel so I had longevity on my side. I thought that for sure by the time I’d finished it, I would be better. I would have found some way out of the forest.

I was always drawn by the voice of a character, the rhythm, the intricate nuances of speech. Their words were truly songs. Right there was music, my crossover point, the bridge between the worlds of dance and words. As a body-oriented person I could clearly see how my characters moved in the landscape around them but I had to lean in harder to notice exactly how they were dressed, and what they were eating. The magically surreal world comes easier to me than the stone-cold facts. But it’s in grounding my stories that they will fly, and I know that. I’m still learning. And my characters live on the peripheries of life, never quite fitting in. They are borderline folk, as am I because that is where illness continues to place me. It irks them just as deeply and as frequently as it irks me. But there is beauty as well as madness in the disequilibrium of a borderland space, that is, if you can find it.

Illness is never kind. I wrote that first novel under its original title The Softest Grey that in its first draft got shortlisted for The Brit Writer’s Award 2011 but I never found a way out of the forest. That first novel eventually got shafted and another one was started. Then came the realisation that shorter pieces of fiction would work better with my state of health so I started to teach myself how to write a good short story. I read and read as much as my illness would allow.

And I’m actually relishing the challenge of the short story, the concision, the sharper edges, the tightness of structure. Some days I’m even loving it!

My story The Passenger is published in Flamingo Land And Other Stories (Flight Press 2015). Another story Mr Forrester Has Wings is available to read on my website

I will always have a complex relationship with my body. In both my darkest moments and in moments of pure joy, I find myself singing; a lament, a song of gratitude, everything is music and rhythm. And rhythm is life. In those moments of song my broken-down, broken-up body bows to the voice. For there is a pain too deep to put on paper, that only the voice comprehends. Interestingly none of my characters to date experience a life-changing illness. A couple of characters in my shorter stories have minor physical disabilities. In time I would like to address that but I find myself dealing with a second illness diagnosis this year. Illness on top of illness makes a mountain and I am just about navigating the harshness of that new landscape. When I can articulate and transform it, when I can attempt to placate or shock it into a new shape, maybe then I will write about it.

Finding love and moving proximal to water to live with my partner have both subtly shaped my writing. In an interesting way there’s less completion, more curves, more translucency and a whole lot of honesty. And I’m still looking for a way to belong. My stories help take me there. They help mend a broken body and my characters step forward to offer advice during my darkest hours. They offer me a place to rest my body. I am learning to live as richly as I possibly can in the real world but I crave and appreciate the alternative landscape. The line between imagination and reality is beautifully tenuous and that is probably my saving grace.

You’re always stronger than you think. I’ve learned that over this last year. Also there is beauty in madness and in the most ugliest of moments. Actually I think that is the most important thing I learned from dance; the perseverance, the sweat, the tears, the almost-broken-from-endless-rehearsals-body that forms the kind of beauty on stage that makes grown men and women cry. It’s hopeless honesty.

The stage was a preparation for life for me. And my writing is a form of faith….’

Next week’s blog, MY OUTING, will be the first of five describing my struggles with cross-dressing as a child, being targeted as an adult by the UK press, and why I like being a trans person.

ABOUT LESLIE TATE’S BOOKS:

I interviewed Lisa Dart, finalist in the Grolier, Aesthetica and Troubadour Poetry Prizes and author of The Linguistics of Light (poems, Salt, 2008), Fathom (prose

I interviewed writer Julia Lee Barclay-Morton about her experience of autism. Julia began as an experimental dramatist in New York, moving to the UK to

I interviewed Gillean McDougall from Glasgow, who edited the collaborative projects Honest Error (on Charles Rennie Mackintosh and his wife Margaret Macdonald) and Writing the

I interviewed French writer Delphine de Vigan, whose book, No et moi, won the prestigious Prix des libraires. Other books of hers have won a clutch

I interviewed Joanne Limburg whose poetry collection Feminismo was shortlisted for the Forward Prize for Best First Collection; another collection, Paraphernalia, was a Poetry Book Society Recommendation. Joanne

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |