LISA DART – SURVIVAL POETRY AND THE VOICES OF EXPERIENCE

I interviewed Lisa Dart, finalist in the Grolier, Aesthetica and Troubadour Poetry Prizes and author of The Linguistics of Light (poems, Salt, 2008), Fathom (prose

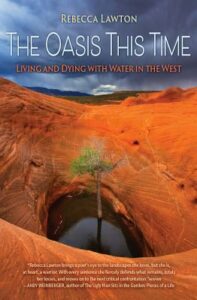

I interviewed Rebecca Lawton, scientist, river guide and prize-winning author, about her expertise in nature, conservation, water, and climate. Rebecca has directed research at a community watershed organization in northern California and designed and managed numerous stream studies and projects in citizen science. She is currently Executive Director of PLAYA Summer Lake, Oregon, a residency program for artists and scientists.

Between the data and policy change is where the arts live.– Bill Fox

Leslie: Tell us about the artist and scientist residency program at PLAYA in Summer Lake, Oregon, that you direct. What’s special about how it works as a creative retreat?

Becca: PLAYA is a 65-acre, park-like property with facilities for artists and scientists to come, stay in private accommodation, and do deep work on special projects. We are right on the edge of the Great Basin, in a unique, arid setting in south-central Oregon. The program was established by some visionary founders, Julie Bryant and Bill Roach, who purchased former ranch land that had become the site for a bed-and-breakfast inn. Bill and Julie rebuilt the public Commons area and eight cabins from the ground up. In 2011 PLAYA opened its doors to the first cohorts of creative individuals who could benefit from the gift of time and space to make progress on artistic and scientific work. I discovered PLAYA after winning the 2015 Waterston Desert Writing Prize for the proposal for my newest book, The Oasis This Time: Living and Dying with Water in the West. Back then, the book was nowhere near done, just an idea gleaned from time in various North American deserts. Because the Waterston Prize includes a month-long award residency at PLAYA, I went there to make progress on writing the book. After two residencies at PLAYA, all of which were extremely productive times for me, the directorship of the center came open. I applied — I was eager to keep the place going, to get a chance to nurture the work of others, and to see PLAYA continue in its challenging physical setting.

PLAYA is special in that it’s hugely remote, in a deeply gorgeous natural place. Whether or not residents come to respond to the beauty here, to a person everyone does. All in different ways, some of which may not show up in their work for years and some that manifest immediately. Artists of all kinds (e.g., painters, dancers, photographers, essayists, poets, musicians) dialogue with scientists in many disciplines (e.g., anthropology, geology, neuroscience, sociology) to begin or finish books or exhibitions, research papers, collaborations. Our mission is to transform the world through creative inquiry, and we’re doing it — one creative residency at a time.

Leslie: Could you enlarge, please, on your statement: ‘I’m keeping up my own writing practice, instigated by the same light and space that inspire our residents’.

Becca: I wish I were keeping up BETTER with my writing practice, but I do allow time every morning to write by hand. Even though there’s little space in my life at the moment for a big project, I’m collecting snippets from this place: the light, the wildlife, the people, the dynamic weather. No doubt these pieces will find their way into my next big project, whatever it shapes up to be. I do have two works in progress, one a novel that takes place in Alberta, one a collection of short climate fiction (cli-fi).

(You can read about Rebecca’s books here – Leslie.)

Leslie: How do water and rocks inspire your writings?

Becca: Water was my first and always subject. I don’t know when I’ll write myself out of water-related material, but it could happen. I’ve been fascinated with moving water since I took up river-running in 1973. I can’t say I’d always been at home on the water—I especially feared our family sailing trips when I was little–but I did feel myself both enthralled and safe when I found the canyons and culture of guiding. My fascination with rocks sprung from my love of water, oddly enough, because the rocks I studied and learned from were generally water-lain rocks: ancient river sandstones, stream beds and banks, water-transported fossils, muds and silts.

Being immersed in water as a medium, one that creates or affects stone, naturally leads to a kind of tension: the fluid actor and the solid matrix on which it acts. There is a story there, arising from those engaged or opposing forces, always.

Leslie: Who have you learned from, and why them?

Becca: My mother: love of the outdoors. My father: persistence and staying positive. My siblings: fun and independence. My daughter: sensitivity and love. My husband: acceptance and grounding. My teachers (other boaters) on the river: you can do this. My middle-school music teacher: great belief in self and courage. My high-school music teacher: humor and beauty. My guitar teachers: learning the difference between what is difficult and what is impossible. My river friends: you’ll always be part of something much bigger than yourself.

These are only a few teachers in my life. ‘Why them?’ I’ve just been lucky enough to cross paths with some amazing, caring people, to whom I have listened.

I’ve also learned a ton from non-humans. The Grand Canyon: big challenges take hard work but offer huge, unpredictable rewards. Northern Utah and Central Oregon: be kind. California: cool on the outside may be truly cool but not because of appearances. Birds and wildlife: survival requires your constant attention. Rivers: so much goes on beneath the surface—pay attention.

Leslie: What have been the crossover experiences in your life linking scientific study to the expressive arts?

Becca: When I worked as a guide, I kept journals of dialogue, observations, snippets of songs, ideas for stories. I felt I was in a story, one that needed to be told, and that I’d be among those who told it. This propensity for storytelling carried into my geologic studies, which I undertook to learn how earth processes worked. I quickly found the texts and scientific writing unreadable. The teachers were fascinating — they’d learned through their love of subject to tell great stories — but it wasn’t happening on the page. I was moved to tears, to utter frustration, trying to interpret what a scientist meant. Worse were the journalists, not trained as scientists, who wrote long and complicated explanations that employed metaphors that just weren’t working for me.

Then, as a person who came to science to learn its stories and then got sucked into its minutiae (because oh my god it’s fascinating), I came to do the same thing. In the 1990s and 2000s I worked in watershed research, and the presentations we gave to the community were met with blank stares. One farmer even came up to me and said, “Your stuff gets boring.” Plus we just weren’t getting some important concepts across. In Sonoma Valley, where I worked, we’d had a blue-ribbon, local steelhead run that was nearly gone. The streams had been drained for urban and agricultural use, and the fish were not able to survive the summering-over part of their life cycles. And we had tons of data, but we couldn’t elevate it to a place of action and policy.

Then, on a Fulbright Scholarship in Canada, I researched climate, water, and communication and learned that activism and policy about natural disaster (such as drought, drying streams, and extreme wildfire) had been well studied by sociologists. Key teams in Australia, on the driest continent, had shown conclusively that communities aren’t moved to change behavior until a situation is codified in story and song. The bush poets, the aboriginal songlines, these were effective in defining a culture and motivating cohesive action.

Or, as my friend Bill Fox of the Center for Art and Environment in Reno says, “Between the data and policy change is where the arts live.”

After learning all that, over years of hard work and immersion in painful observations, I never wanted to go back to my old ways of sharing data. I wanted to live where the arts — and good storytelling — live.

Leslie: How do you try to balance the various doing and being roles you play, e.g. activist, manager, environmentalist, writer and thinker?

Becca: I happen to be an extreme introvert—according to the Meyers-Briggs test, I am as far into introversion as one can go. I didn’t learn that until my thirties. I knew I was different, exhausted by basic interactions, but I didn’t know why. From the day I was told that, I understood that everything I do involving other people, as much as I may love it, has to be balanced by equal or greater amounts of solo time. Writing became a natural pursuit, an outgrowth of introversion, a place to be alone but ultimately in community. Thinking, too, lands in that intro space I suppose. But activism has never been a great match for me—not that I don’t find it important, I just can’t sustain too much time in a crowd, group, or movement.

Managing others has always been something I love and respect as a worthy pursuit. One has to be so intuitive about the skills and care of others, though. It’s a rare talent and one I work hard to cultivate. Therefore directing PLAYA is a natural fit for me although not without challenges. I’m not big on top-down management—I like to move a team toward a vision, but I want that to be a shared vision and done in an organic way. At PLAYA, we seek every day to find the balance of individual contribution with a collective sensibility. We’re a group of highly competent specialists who also have generalist abilities. Our work is to provide a place for extremely creative and accomplished people from all over the world to feel at home, nurtured, and protected.

I recharge my easily flattened batteries by reading, writing, watching birds, playing music on mandolin and guitar, walking, and meditating (I have a daily practice of sitting in the Insight Buddhist tradition). Then I come back to the work.

Leslie: What is at the heart/centre of your relationship to nature?

Becca; My love of family. I grew up learning to love nature through experiences with my mother, father, two brothers, and one sister. I like to say we were outdoorsy outsiders, because we weren’t connected so much to our community as we were to each other. Not to say my parents weren’t community minded — they were. I have fond memories of them supporting our school, neighborhood, and network of good friends. But it was the journeys we took — whether nearby or distant — into natural settings that were so deeply affecting and pervade everything I do. My mother’s father was an avid outdoorsman, even did some guiding in the Adirondack Mountains, and my mother became a naturalist and environmental teacher. My brothers are geologists and geographers. My sister was a river guide and National Park Service ranger and now travels extensively. Of those in our family, I guided the longest, in part because of the community I found there—the people I worked with who had my back. Being outdoors, with those strong alliances of family and friends, weaves a love of nature through everything.

Next week poet and artist David Coldwell talks about Marsden village, a centre for poetry, art, festivals and walking.

ABOUT LESLIE TATE’S BOOKS:

I interviewed Lisa Dart, finalist in the Grolier, Aesthetica and Troubadour Poetry Prizes and author of The Linguistics of Light (poems, Salt, 2008), Fathom (prose

I interviewed writer Julia Lee Barclay-Morton about her experience of autism. Julia began as an experimental dramatist in New York, moving to the UK to

I interviewed Gillean McDougall from Glasgow, who edited the collaborative projects Honest Error (on Charles Rennie Mackintosh and his wife Margaret Macdonald) and Writing the

I interviewed French writer Delphine de Vigan, whose book, No et moi, won the prestigious Prix des libraires. Other books of hers have won a clutch

I interviewed Joanne Limburg whose poetry collection Feminismo was shortlisted for the Forward Prize for Best First Collection; another collection, Paraphernalia, was a Poetry Book Society Recommendation. Joanne

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |