LISA DART – SURVIVAL POETRY AND THE VOICES OF EXPERIENCE

I interviewed Lisa Dart, finalist in the Grolier, Aesthetica and Troubadour Poetry Prizes and author of The Linguistics of Light (poems, Salt, 2008), Fathom (prose

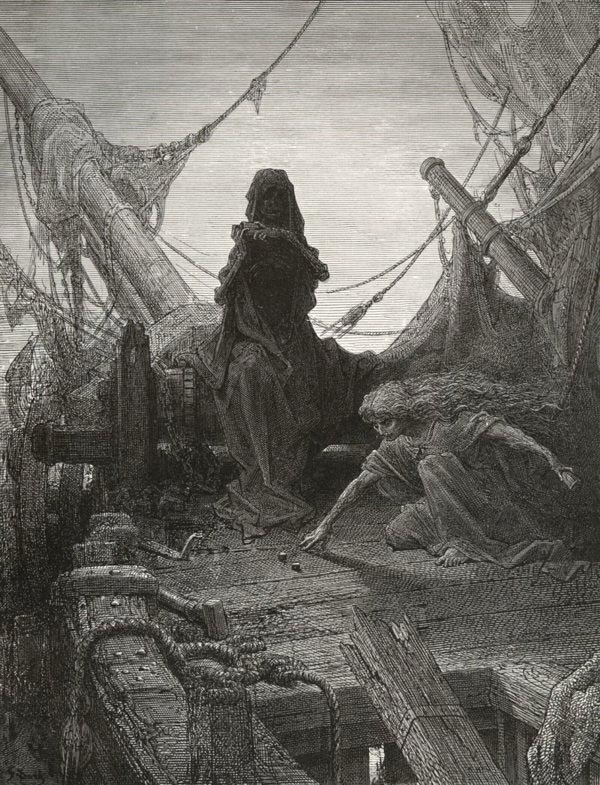

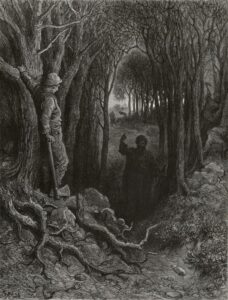

Like one, that on a lonesome road/Doth walk in fear and dread,/And having once turned round walks on,/And turns no more his head;/Because he knows, a frightful fiend/Doth close behind him tread – Coleridge.

I’ve always been afraid of the dark. As a child I’d creep across the landing with my back to the wall so I could fight off ghosts. In the bathroom I was menaced by mini-devils who jumped out of sight whichever way I turned. I remember lying awake listening to The Quatermass Experiment on TV. I was four at the time and I’d glimpsed the shots of the crashed spaceship before being sent to bed. Imagining the story and hearing weird music rising from below was almost worse than seeing the programme itself.

In bed I slept with the pillow over my head to block out the dark. If criminals or monsters were sneaking up on me, I didn’t want to know. Even today, if I get up in the night, I sometimes imagine I’m being watched or followed. And when I’m alone I sleep with the door open and the landing light on.

According to Freud, fear of the dark results from separation anxiety disorder (SAD). The child is afraid that a much-loved place or person, often a mother, will be taken away. I think in my case separation anxiety began in the maternity hospital just after birth. Between feeds, all the mothers were kept away from their babies. Afterwards, at home, my mother had problems with her milk flow. I have pictures showing how thin we both became.

I remember having other anxiety symptoms as a child. So I dreamed of contracting a life-threatening illness and being rushed into hospital. Closing my eyes, I saw myself lying there with my chastened parents gazing at me in a state of shock. It was my revenge – they’d not believed the signs, now they had to listen. I forgave them, of course, and pictured my homecoming, where I was treated like royalty. So I lay in bed and feasted on cake and fizzy drinks and strawberry ice cream. My imaginary timeout continued with weeks off school, followed by a return on crutches or in a wheelchair with my classmates smiling nicely and being extra-kind because ‘you can’t hit a man when he’s down’.

I also dreamed of being captured by boys on the way home from school. They grabbed me, frogmarched me to the waste ground and tied me to a tree. After a long night I was rescued by the police, questioned and exonerated. My parents were horrified, the bully boys were found out and I was awarded a medal for bravery.

My fears were often ambivalent. For instance, I was afraid of climbing into the water at the swimming baths but loved the sea. On holiday I’d wade out waist-high and splash and jump or float on my tummy in the shallows. I loved the wild freedom of the sea but I never learned to swim. I had a similar love-hate attitude to spiders, shivering as I watched their fat black-and-yellow bodies fixed like jewels at the centre of webs. And as I grew older, my own body became increasingly fascinating and ugly. So I kept myself covered, using the excuse that my skin burned easily, and I chose to walk alone in the countryside, where no one would see me.

![mariner_won[1]](https://leslietate.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/mariner_won1-229x300.jpg)

So I sneaked out of the house at midnight using my key and crept round to the local graveyard. My chest was tight and my teeth were chattering but I forced myself through the gate then stopped dead, thinking I heard a noise. It was high and weird like the music I’d heard during Quatermass. It sounded half-human, half-animal and dangerously supernatural. I turned and ran, only slowing when I reached a safe distance. When I sneaked into the house I slipped into bed and put my head beneath my pillow.

I didn’t challenge the dark again.

ABOUT LESLIE TATE’S BOOKS:

I interviewed Lisa Dart, finalist in the Grolier, Aesthetica and Troubadour Poetry Prizes and author of The Linguistics of Light (poems, Salt, 2008), Fathom (prose

I interviewed writer Julia Lee Barclay-Morton about her experience of autism. Julia began as an experimental dramatist in New York, moving to the UK to

I interviewed Gillean McDougall from Glasgow, who edited the collaborative projects Honest Error (on Charles Rennie Mackintosh and his wife Margaret Macdonald) and Writing the

I interviewed French writer Delphine de Vigan, whose book, No et moi, won the prestigious Prix des libraires. Other books of hers have won a clutch

I interviewed Joanne Limburg whose poetry collection Feminismo was shortlisted for the Forward Prize for Best First Collection; another collection, Paraphernalia, was a Poetry Book Society Recommendation. Joanne

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |