JANE BURN – POETRY AS HARD GRAFT, INSPIRATION, REACTION OR EXPERIMENT?

I interviewed poet & artist Jane Burn who won the Michael Marks Environmental Poet of the Year 2023-24 with A Thousand Miles from the Sea.

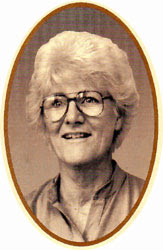

Jill Hipson has been completely deaf since the age of five. To illustrate what profound deafness really means, Jill described (in writing) a typical domestic scene:

‘The world of sound simply isn’t there for me at all. I only know there are sounds if there are vibrations too. For example, this morning I was trying to tell my hearing husband Chris something in the kitchen while waiting for the kettle to boil. He can understand my voice if he looks at my face at the same time; in return he gestures and fingerspells his responses.

Chris, (Cupping his hand over an ear and shaking his head) – meaning: ‘I can’t hear you’. (Points to kettle and fingerspells) “Very loud.”

Jill: (Speaking) “I didn’t realise it was that noisy.”

Chris: (Nodding his head and mouthing) “Oh yes.” (Fingerspells) “It sounds like a plane taking off.”’

Jill lives a complex life. She teaches deafness awareness and British Sign Language (BSL) to hearing people ,

she edits a monthly church magazine, reads widely and is culturally active in both the deaf and hearing communities.

Over the years, meeting Jill and exchanging many pages of questions and answers, I’ve learned about a whole new world with a language and poetry of its own. I asked Jill, in writing, about the cultural experience of deaf people: what they enjoy, the barriers they face and the rich culture they share within their own community.

Leslie: For obvious reasons, deaf people rarely attend events aimed at hearing audiences. If all shows were signed or subtitled or had a written script available, would that help?

Jill: I’d like to start with a look at cinema and film subtitling. When my kids were little, I used to have to sit through a lot of films with them which weren’t subtitled. Unfortunately, films at the cinema are seldom captioned and usually only once in the run of showings for each film… And the subtitled screening is often at awkward times like 11am on Monday mornings. But when I watched these un-subtitled films I found I noticed far more about the visual details. Things like the wonderfully subtle facial expressions Jason Isaacs had when he played Captain Hook in ‘Peter Pan’. When I watched the film again on TV with subtitles I didn’t notice this sort of thing because I was too occupied with reading the captions. The fact of the matter is, when one’s eyes have to do double duty as one’s ears, it’s impossible to notice everything. Deaf people suffer a lot from concentration fatigue!

Remembering that British Sign Language is quite different from English, subtitling is only useful for deaf people whose first language is English – although intense concentration is still needed to watch the subtitles and glance at the action. Signing can relay some of the performance but you have to watch the signer all the time. If you look away, you’ll miss what’s being said. The best results for me are when I know the play well and can go along and know what’s going to happen. A synopsis helps a lot too.

Leslie: How does it feel to be sitting in the audience at one of these spoken events without aids and adaptations?

Jill: It’s more that some shows are more suitable than others to be signed or captioned. Stand-up for instance would be a dead loss as the humour depends heavily on delivery, tone of voice and is all tailored to how the audience is responding. In addition, ‘hearing’ humour translates very badly into BSL and vice versa. Pantomime is another one where the banter tends to pass me by – I like watching visual humour instead. I think also events involving music do not go well into captioning or BSL – I’ve sat through a subtitled opera and I was bored to tears. You need both the content and the music.

Going to a musical performance with a written script – this doesn’t do it for me or most deaf people. I’ve felt acutely alone and isolated at these types of events. Looking up from the script, I noticed audience members laughing but I’d no idea what they were laughing at. I had the lyrics for some of the songs but this only gave me part of the experience. One song looked quite straightforward but I looked up from the lyrics and noticed everyone around me was crying.

To give another example from cinema without subtitles – the horror film ‘The Village’ by M Night Shyamalan. My kids were absolutely terrified by this film and hid behind the seats for most of the showing. I sat through it saying, “Yeah, yeah the monsters have turned up, now they’ve gone.” Usually I scream my head off throughout horror films (I had to abandon ‘The Woman in Black’ because I was screaming so much my dog was frightened). Discussing ‘The Village’ with the kids afterwards, I found out that the soundtrack was very scary indeed. Very, very scary. And all this had passed me by.

Compare this with church. I go to an Anglican church where the format for Holy Communion follows Common Worship, the preacher gives me a copy of his sermon and the person doing the intercessions gives me a copy of their prayers. I can read this and enjoy ‘singing’ the hymns and I don’t feel left out. I find that this sort of experience lets me have time and space to pray and reflect. The only bits which jar are when the choir are singing and I don’t know what it is, or someone ad libs, or one of the prayers being used isn’t in the service booklet. I avoid ‘happy clappy’ type worship like the plague. It’s far too ad hoc and I feel excluded. Funerals are always difficult – because it’s an emotional time, it’s difficult to ask for the sermon or the prayers. I once caused massive offence inadvertently after the funeral of my speech therapist, who I was very close to, by explaining to her granddaughter that I couldn’t understand the readings they’d used and would she mind showing me in the books they’d used. I tend to go to funerals and put up and shut up these days. The worst ever funeral I’ve been to was a Humanist funeral – people reading from the deceased friend’s favourite books and poems, and Country and Western music. I really felt totally excluded but wanted to pay my respects (she’d had Motor Neurone Disease and had left a young family) so I just gritted my teeth and thought about her.

The only time I’ve been to a music event and felt included on the same level as everyone else with normal hearing was my brother-in-law’s 50th birthday party. His heavy metal band played all evening. I sat or danced right next to the bank of speakers. Of course the big beat came through my skull, and though I wouldn’t go out of my way to seek that experience again, it was a good evening.

Leslie: What kind of cultural events do deaf people generally get involved in?

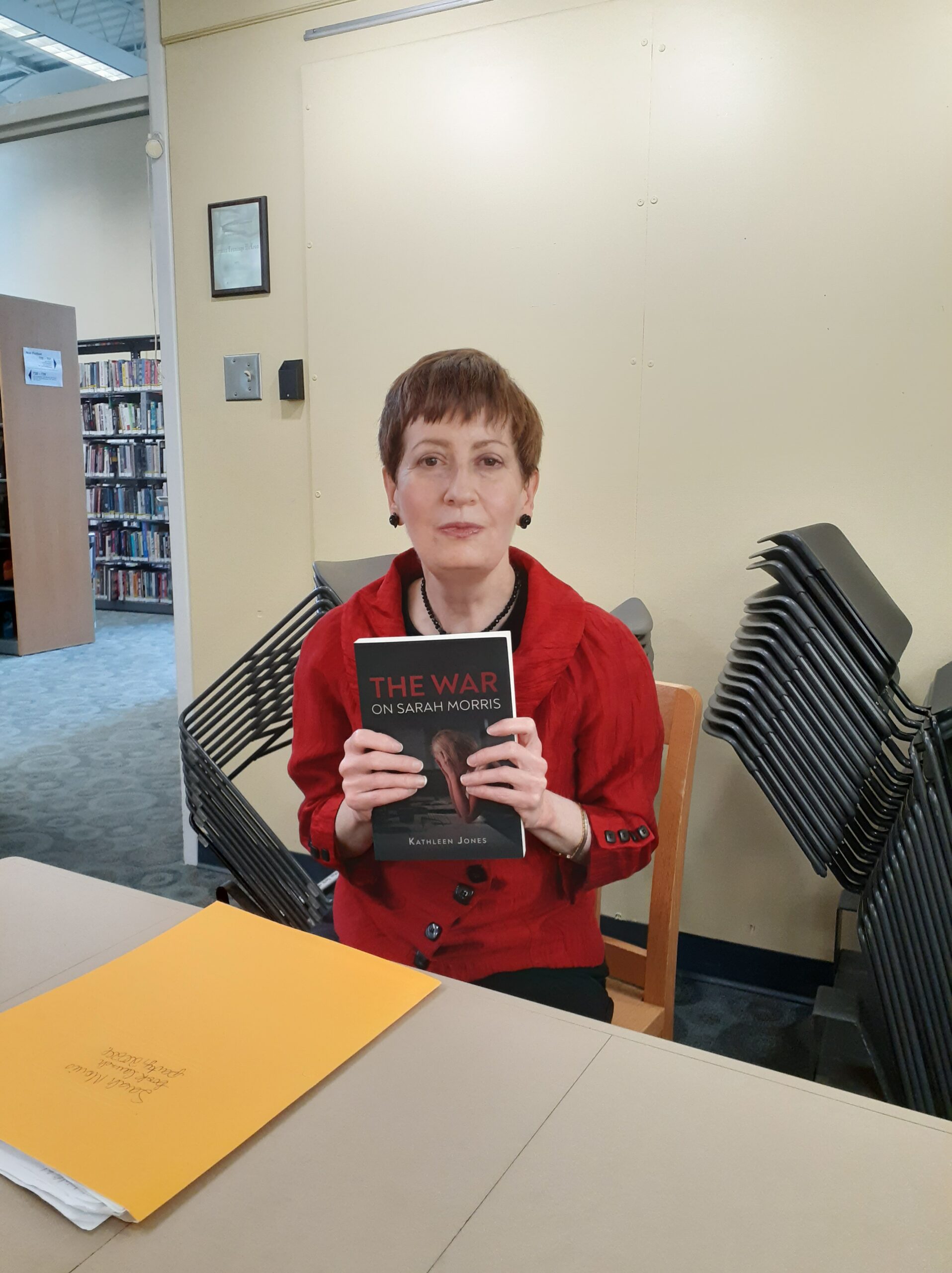

![picture-33[1]](https://leslietate.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/picture-331-300x199.jpg)

I think in general deaf events tend to be more visual. I remember reading about a Deaf Retreat Weekend. The organisers realised that doing the usual sort of things would not be very restful for deaf people. Instead of people reading out loud, talking and singing they had painting, sculpture, woodland walks, and quiet time where everyone prayed on their own.

Leslie: I think we’re both admirers of BSL poetry – what’s it like, in a nutshell?

Jill: BSL poetry is completely silent. It is entirely visual with no spoken element. Poetry created in BSL uses the characteristics of the language, for example by repeating handshapes or movements that the hands make. It looks like a visual ballet with hands and facial expressions. Translating from English doesn’t have the same effect; it is like translating from a foreign language into English. Something gets lost in translation.

Leslie: How did Dot Miles change BSL poetry? How has the form changed or developed since her death?

Dorothy Miles was the first person to create BSL poetry. She first saw this art form in America, using American Sign Language (which is very different to BSL) and started creating BSL poetry once she moved back to the UK. In the years since her death, several BSL poets have become visible in their own community. But none, to my mind, have produced anything as startlingly original as Dorothy. Most BSL poets talk about their own experiences – think about the difference between Pam Ayres in the ‘homespun poetry’ corner and Carol Ann Duffy in the highbrow corner and you’ll get the idea. I very much admire Paul Scott’s interpretations of Dorothy’s poetry; he gives it a modern slant and makes it look more edgy than she was able to when she created the poems.

Leslie: To end with, do you have any tips for hearing people if they’re present at performances involving deaf people?

Jill: Just a couple. Firstly, deaf people don’t clap they wave, and secondly, deaf people read body language – which means they can see the true feelings behind the words.

I interviewed poet & artist Jane Burn who won the Michael Marks Environmental Poet of the Year 2023-24 with A Thousand Miles from the Sea.

I interviewed ex-broadcaster and poet Polly Oliver about oral and visual poetry, her compositional methods, and learning the Welsh language. Polly says, “I absolutely love

I interviewed Jo Howell who says about herself: “I’ve been a professional photographic artist since I left Uni in 2009. I am a cyanotype specialist.

Poet Tracey Rhys, writer of Teaching a Bird to Sing and winner of the Poetry Archive’s video competition reviews Ways To Be Equally Human. Tracey,

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

10 responses

I was intrigued by Jill’s experience in cinemas. I have the same problem. I want to persuade film producers to bring out films with subtitles built into every copy, but, because they would annoy any hearing audience, they should be visible only if the deaf person is wearing special glasses. It could be done, I am sure, but I don’t know if the cost would be prohibitive. And I don’t know how to go about building a following, large enough to influence the outcome. Would Jill know? (I enjoyed meeting you again after, what, ten years? Every success, kiddo, every success and happiness, to you and Sue.)

Thank you Julia. Yes, it was great to meet you again and thanks for the good wishes and a lovely evening. I’ll alert Jill to what you’ve said.

Thanks for bringing Jill as a guest. It has provided me with a great insight into something I had very little knowledge about. I am fascinated by BSL poetry and I’ll investigate further. Thanks and all the best.

That’s really good to hear, Olga. I’m so pleased. The link in the article to Paul Scott takes you to some BSL poetry performances. Dorothy Miles is my personal favourite and the person who began it all. 🙂 🙂 🙂

A fascinating post Leslie and Jill, hearing is something most of us take for granted and this has definitely given me something to think about. I know that I am not keen on watching subtitled foreign films for the same reason that you mention. You miss a great many facial expressions and nuances, but at least the sound track is often a guide to the change in atmosphere and without those audio clues, so much is missed. I hope that as new technology is developed, there is more emphasis on creating a much better experience for hearing impaired and sight impaired viewers.

Absolutely. Thank you, Sally.

This is a fascinating read. The idea of silent poetry is amazing.

Yes, and it’s interesting to try to translate as the conventions, as well as the language, are different. I found this out when performing with Jill, using simultaneous BSL/English (and trying to keep in synch)!

A fascinating read and I have learnt much..Mime always held a fascination for me as a child I am guessing BSL is an extension of that maybe ?

Thanks, Carol. I’m not an expert, but my impression is that BSL is like Chinese Characters. There are elements of mime, but also conventionalised signs. In BSL poetry Dot Miles made up new signs, which at the time was frowned upon by conventional users but today is much admired by other BSL poets. Signing involves mouth/face gestures as well as hands, so mime is certainly present but more abstracted gestures do exist I believe. I’m open to correction on any of that since everything I know is thanks to written conversations with Jill. I don’t sign myself. What I do know is that BSL is a completely different language to English.