SARAH ROSS-THOMPSON AND THE ART OF COLLAGRAPHED PRINTS

I interviewed artist Sarah Ross-Thompson whose exceptional Collagraphed prints use fabrics, lichen, porridge and string to create images of the dramatic Scottish Highlands where she

Our attitudes to disability touch us personally. Quoting the disability rights slogan ‘Nothing about us without us’ Emma Claire Sweeney guest blogs about her sister Lou, looking at the whole person, not the label. Emma, who has a Creative Writing MA from UEA and writes for The Guardian, The Independent and The Times, also reflects on her own struggle to find words that truthfully represent Lou’s experience…

‘Some of my most prominent memories of my grammar school days in Birkenhead relate to my sister, Lou, even though she attended the special school across the other side of town. After a swimming lesson in the early nineties, for example, an older boy referred to Lou as a ‘spaz’. I still remember the sudden strength I acquired when I pinned him against the wall, seeing it as my role to speak up on her behalf.

Not long after this, I complained to my first year English teacher about the use of the term ‘idiot’ in Nina Bawden’s Carrie’s War. Mrs Nuttall generously responded by devoting one class to a debate on the subject. It is only in writing this that I realise the extent to which I am indebted to my former teacher. She legitimised and focused my fierce (and, in hindsight, somewhat misplaced) sense of injustice at the inadequacy of literary representations of learning disability.

I had yet to find in the novels and poems I devoured a portrait of a family that resembled mine, and so, with the help of Mrs Nuttall, my inarticulately angry response to that boy at the baths was now being funnelled into a creative process that allowed me to speak up on behalf of those who, like Lou, lacked the language or comprehension to tell their own stories. My first ever secondary school creative writing assignment, for instance, was about a girl trying to decipher a phrase that her sister kept repeating indistinctly.

Even back then, I suspected that most people had misconceptions about learning disability, and that fiction and poetry could help to subvert them. Have you ever assumed that, deep down, a sibling must inevitably resent his sister or brother with learning disabilities? That the life of someone with learning disabilities must be overwhelmingly bleak and is therefore deserving of pity? That families who raise their disabled child at home are somehow saintly in their powers of endurance?

When I mention Lou’s cerebral palsy and autism, I am usually offered sympathy on the assumption that her life must be miserable and my childhood must have been tough. This is hardly surprising given that as recently as 1983, when Lou was diagnosed, the doctor told my parents to focus their love on her twin, Sarah, and on their eldest daughter, me; put Lou in an institution; forget there had ever been three.

If only he could see us now: Lou leading the way onto the dance floor, throwing back her head in laughter, singing along to the lyrics; Sarah and me and our parents following in her wake, looking on – half in apology, half in admiration – as she elbows her way between couples, getting the men to dance with her. Her lack of inhibition gives us an excuse to join her on the dance floor: she’s always the first to get up and the last to leave.

Keenly aware that I was in the early days of studying my craft and alert to the importance of a sensitive representation of learning disability, throughout my twenties I wrote about other subjects. And yet, I never doubted that my pen would one day return to this.

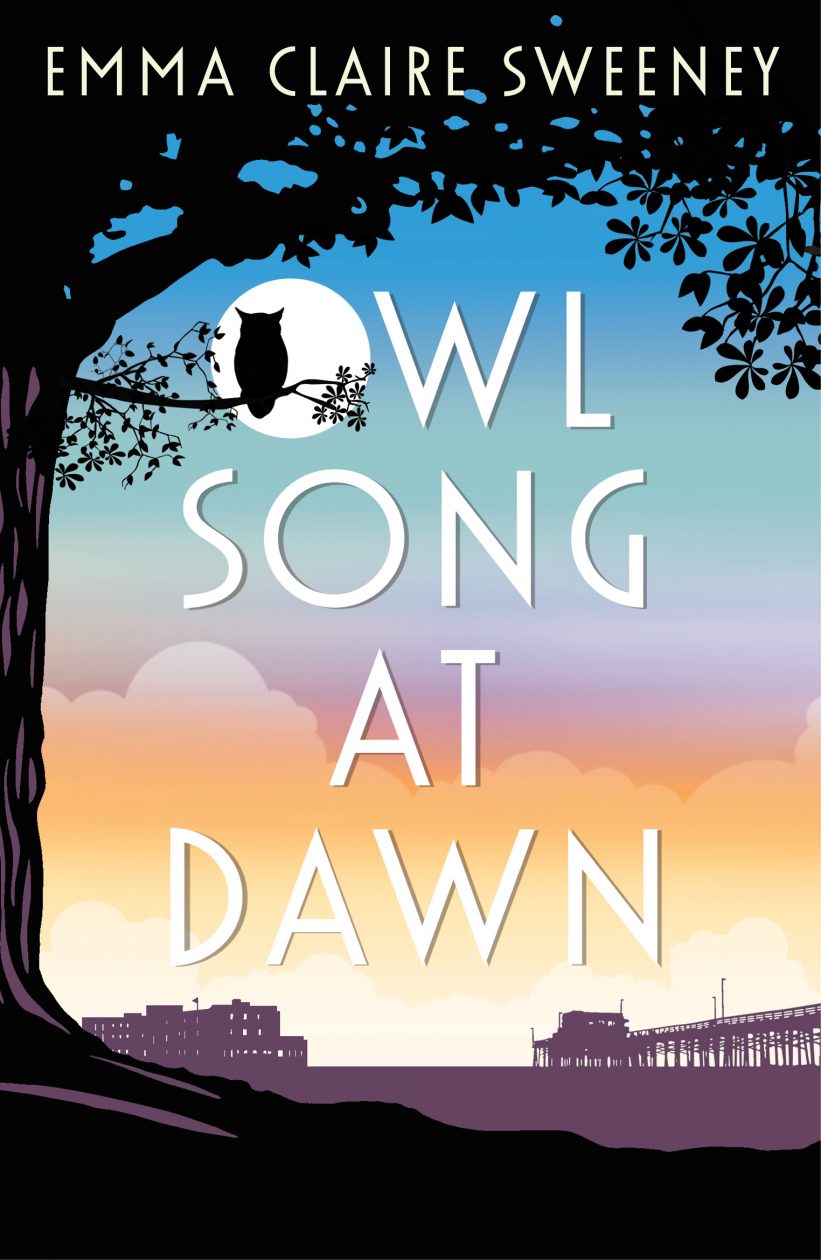

As a schoolgirl, I had failed to comprehend the moral minefield of “Nothing About Us Without Us”, which had not yet become the slogan of the disability rights movement. But when I returned to the subject of learning disability as a professional author in my thirties, I began to feel uneasy about my early notions of speaking up on behalf of someone else. My early attempts to give voice to a fictional character with learning disabilities in my novel-in-progress, Owl Song at Dawn, had resulted in the kind of patronising, infantile qualities that I was trying to undermine. Could this not disempower the very people I was trying to help?

When I was awarded an Arts Council residency at Sunnyside Rural Trust to work with a group of adults with learning disabilities to compile an anthology of life stories, I had no idea what form the vignettes would take. It was only when I listened to the recordings I had made during the year that I realised I was listening to poetry – a new kind of poetry, but one I found half-familiar because it shared some of the qualities of my sister’s language: a language I have spent a lifetime trying to learn. I realised that I could write poems using only the words and experiences of the participants, that through repetition and placement even a narrow range of phrases could take on diverse meaning, and, that by listening with the heart, readers might feel as if they have understood something that has been expressed through fracture and lacunae as well as through coherence.

And, so, the poets at Sunnyside helped me to find a solution to the voices I was struggling to render in my novel. I began transcribing all the things my sister said to me during our nightly phone-calls:

Cheeky pie and custard don’t forget the mustard. What’s your name? My name’s Louise Katherine Sweeney, 31 Grange Road East, Claughton, Merseyside. Where’s Sarah? Sarah’s in Leeds. Where’s Seth? My nephew. Seth’s laughing at me! You’re drunk! That’s not funny. What noise does a cow make? Moooo. Who do you love the best, Mum or Dad? You’re stupid. You stink! I like tractors. I like owls. Twit-twoo, I love you true. More than words can say. Tiger, tiger burning bright, in the forest of the night. Night, night, sleep tight, make sure the bugs don’t bite.

In my revised novel, I have attempted to capture something of Lou’s language in the voice of Edie, my character with learning disabilities. Of course, I have simultaneously adapted it for the character who was born in the 1930s in Morecambe and whose seminal life experiences are radically different from Lou’s.

In my revised novel, I have attempted to capture something of Lou’s language in the voice of Edie, my character with learning disabilities. Of course, I have simultaneously adapted it for the character who was born in the 1930s in Morecambe and whose seminal life experiences are radically different from Lou’s.

This redrafting trajectory of Owl Song at Dawn took me closer to an appreciation of the kinds of stories that Lou is already expressing with her melodic and quirky turns of phrase. Lou and the Sunnyside poets together taught me to avoid speaking up on behalf of people with learning disabilities, and instead to attempt to narrate with them.’

Emma Claire Sweeney has a PhD on literary representations of learning disability and currently teaches on City University’s Novel Studio and at New York University in London. With her writer friend and colleague Emily Midorikawa, Emma runs the website Something Rhymed, which shines a light on the forgotten friendships of the world’s most famous female authors. Emma’s novel, Owl Song at Dawn, is now published and can be bought here. It has been longlisted for the Guardian Not the Booker Prize and Emma has appeared in The Guardian and on Woman’s Hour talking about her book.

ABOUT LESLIE TATE’S BOOKS:

I interviewed artist Sarah Ross-Thompson whose exceptional Collagraphed prints use fabrics, lichen, porridge and string to create images of the dramatic Scottish Highlands where she

Part 2 of my interview with Mark Statman looks closely at Mark’s Latin American poetic influences, his life in Mexico and ends with an extract

I interviewed international poet and translator Mark Statman about Volverse/Volver, his 14th published collection. Mark, who has won national arts awards, is Emeritus Professor of Literary

I interviewed Lisa Dart, finalist in the Grolier, Aesthetica and Troubadour Poetry Prizes and author of The Linguistics of Light (poems, Salt, 2008), Fathom (prose

I interviewed writer Julia Lee Barclay-Morton about her experience of autism. Julia began as an experimental dramatist in New York, moving to the UK to

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

3 responses

Excellent piece again Leslie – I don’t know where you find the time to pen such vibrant pieces!

Love it – T x

Thank you Wonder Woman Tracey! L x

Very interesting. As someone with serious physical disabilities I’ve been aware of the lack of disabled people’s voices and misrepresentation of disability issues in fiction, and I knew it was even worse when it came to learning disabilities.

To address the lack of severely disabled protagonists I eventually wrote The Single Feather, and set it in the current day, so the ‘scrounger’ abuse directed at those with disabilities could be included.

I will be buying both the poetry and novel, it needs more people to think about diversity and for that to include disability including learning disabilities. So, all that’s left is to wish her (and her sister) the best of luck,