JULIA LEE BARCLAY-MORTON – YOGA, WATER AND REWRITING AUTISM

I interviewed writer Julia Lee Barclay-Morton about her experience of autism. Julia began as an experimental dramatist in New York, moving to the UK to

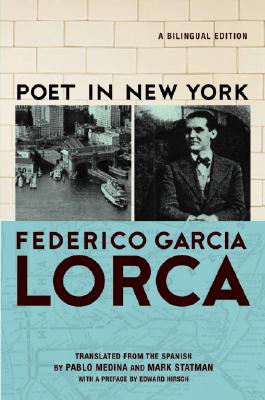

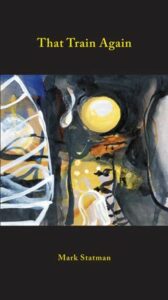

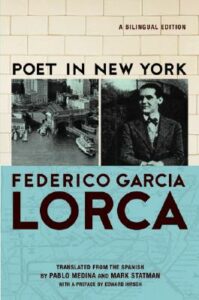

I asked Mark Statman, associate professor of Literary Studies at Eugene Lang College, about Religion and Poetry. His deeply cultured answers reflect the seminal nature of his translations, which include Federico García Lorca‘s Poet in New York and José María Hinojosa’s poetry, plus his latest work-in-progress, a book-length version of Uruguayan poet Martín Barea Mattos. Mark’s own original poetry collections include A Map of the Winds and That Train Again. In thinking about poetry and religion Mark draws on his international experience as both poet and translator.

Leslie: If religion involves a persuasion that something is bigger than us, how similar is poetry – looked at as a reader and as a writer?

Mark: Religion does offer me a way to think about the world that is bigger than myself, precisely because that is the role religion can best play. I want to be clear that I’m not necessarily thinking about the organized religions but religion itself as a way of organizing understanding. I’m not particularly fond of the word spiritual, at least not in the way I hear a lot of people use it – “I’m a spiritual person but I don’t believe in religion,” which to me sounds like a way of saying “I know something is out there but I just don’t want to do any of the work that goes into finding out what it is.”

Poetry helps me think about the world in ways that are both very grand (the infinite, infinity) and intimate (hello, you). Poetry demands I pay attention.

Mary Oliver, in The Summer Day, writes ‘I don’t know what a prayer is’ and then she goes on to write about flopping down in the grass, about watching a grasshopper as closely as she can. She asks ‘what is it you plan to do with your one wild and precious life.’ Which is I think a pretty great way of thinking about what poetry asks.

We pay attention to the world as we understand it, as we could understand it, as we might not understand it. The use of the imagination here, as in religion, is powerful as the great organizing principle.

Blake, in his Prophetic Book Jerusalem, talks about Imagination as the force that allows us to move from Experience to Higher Innocence.

![alphabet[1]](https://leslietate.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/alphabet1.jpg) Gary Snyder, in his essay Language Goes Two Ways, which Christian McEwen and I had the pleasure of including in a book we edited together, The Alphabet of the Trees: A Guide to Nature Writing, writes about the need to use language precisely for seeing. Snyder notes that if we see a wren, and call it that (‘wren’) and just go on walking, then really we’ve seen nothing. He notes that if we “see and watch, stop, feel, forget yourself for a moment, be in the bushy shadows, maybe then feel ‘wren’ – that is how to join a larger moment in the world.”

Gary Snyder, in his essay Language Goes Two Ways, which Christian McEwen and I had the pleasure of including in a book we edited together, The Alphabet of the Trees: A Guide to Nature Writing, writes about the need to use language precisely for seeing. Snyder notes that if we see a wren, and call it that (‘wren’) and just go on walking, then really we’ve seen nothing. He notes that if we “see and watch, stop, feel, forget yourself for a moment, be in the bushy shadows, maybe then feel ‘wren’ – that is how to join a larger moment in the world.”

With poetry we have self and selves, world and worlds. Zen Buddhists talk about interpenetration and John Cage uses the same word, echoing a lot of what he learned from Suzuki. But that’s what poetry does, no? It allows the self/selves to be in this multiple world, and to be creators of it as well. Although the Buddhists might frame this as nothing instead of something, while Bishop Berkeley would think about this in reverse, as something instead of nothing.

There are times when I’m writing, usually it’s poetry but it can be other things as well, I enter a kind of zone in which I lose a sense of myself as self (I think now of the Buddhist use of the word and of ego) and seem connected to something else. It’s a little hard to explain because I enter a state, that despite using language, seems to get beyond language. There’s that startle thing – if my wife or someone comes along and asks me something while I’m working and in that space or zone – and I’m really surprised to find her there. What! What!

Of course, there’s the wonderful part of it, which is revision. This is where the rabbis talk about ‘believing intelligently’. Adrienne Rich talks about ‘loving with her intelligence’, which is the same kind of thing. You can take it on faith that if you’ve written something wonderful in the first thought/best thought mode you better get to work. Which is a little like religion as well, in that it isn’t enough to believe, you have to work.

The rabbis talk about the preparation that goes into contact with God (or call it the Other). And the preparation that leads to understanding of what it leads to. What have you learned? How have you become wise? For me, it isn’t enough to write the poem and move on – in order to revise it, in order to give the poem its proper place in the world, I have to do some real work.

What’s interesting, which is part of the work idea, is that when I’m translating I don’t ever enter that lost-self zone or space. Because translation is more like revision, more like the study of the world rather than the making of something or placing something into the world. Translation, as creative as it seems to me, and as collaborative as it seems to me, has more of an edge of interpretation. There’s less inspiration and unconsciousness (though that’s there) and more conscious discovery of what someone else has placed or created.

Leslie: How do you respond to the Paul Muldoon quote: ‘The process of writing is the experience of recognizing that one is not in command. That one may have some free will, insofar as we have such a thing, but basically one has given oneself over to something beyond oneself. In this case, the language’?

Mark: Two things I think about a lot, one is Keats describing this world as a ‘vale of soul-making’. And if the soul is to be beautiful, then the vale in which the soul is made must have beauty. If the soul is to be loving and loved, than the vale must be full of love. If the soul is to be intelligent and honest, well, the vale etc. And the counter to that is if the vale is ugly, the soul will be. So in poetry? I look to make poetry that will make a great and beautiful soul.

Byron writes: ‘For there is something in me which shall tire / Torture and time and breathe when I expire’. In my life, poetry, like religion, is the force for knowing that something.

Leslie: Coleridge said reading and writing poetry requires a ’willing suspension of disbelief’. Does poetry today still rely on a ‘counter-cynical’ attitude similar, perhaps, to religion? And is that quality being undermined by today’s 24hr news culture?

Mark: The 24 hour news culture really is awful. Because it fills people with a sense that they understand things when in fact all it seems is that they are accumulating a certain kind of unused or useless capital. You can learn facts (which may be accurate or inaccurate) but if you don’t know what the facts mean, what good is it? Paulo Freire writes about knowing the name of a capitol of a state or country, but if all you know is the name, so what? I know Washington, DC is the capitol of the United States but if I have no sense of what that means, of what goes on there, what doesn’t go on there, what it means for the country, what it means for the rest of the world, then my ability to name something is just game-show knowledge. This gets back to Snyder and the wren. It isn’t good enough to have the name.

The 24 hour cycle doesn’t give us a chance to think through meaning, to examine knowledge, to become wise, because the cycle pretends that the cycle itself is meaningful and if you just follow along, well, you know what’s going on! You’re aware! But facts or data without meaning means one doesn’t really know anything. I know Plato said it first, but the cycle in striving for a kind of warped originality, for allowing us all to become our own self-determined authorities on what’s going on in the world, leaves out the fact that, as we read in Ecclesiastes, there is nothing new under the sun (which is why Pound has to be so forceful about telling us to make it new, not to make something else new, but what we have).

So Coleridge’s admonition here is pretty important. We have to stop thinking that each one of us is the center of the whole universe; we have to recognize that our experiences of the world, as wonderfully liberating as they can be, are so very very limited. A lot of times my students will suggest that they don’t want to read a poem because it isn’t ‘relatable’. I know what that means but I have no interest in it. Why does a poem have to contain the reader? Why does the reader have to believe he or she always comes first? I’m not saying that the experiences and knowledge the reader brings to the poem aren’t of incredible importance and that the reader may be thankfully making a whole new poem because of a new reading, I’m just wondering why the willing suspension of self when reading a poem isn’t as fundamental as the reader’s self-belief at the expense of the poet. Why not, as Sammy Davis, Jr sang it, have it all?

Leslie: As poets and poetry lovers, how do we go about welcoming all experience in a state of ‘knowing innocence’? Can religion and religious practices play a part in this?

Mark: Blake is useful here. The imagination is that force that allows us ‘knowing innocence’. I think again of Rich reminding us to love with our intelligence. How else should you love? Stupidly? I had a 4th grade student once tell me, ‘poetry is when I write something I never thought I’d say in a way I never thought I’d say it’. That’s a great knowing innocence. The knowledge of one’s own language, the knowledge of one’s own thinking, and the realization that somehow there has to be a birth of something into the world that is you and beyond you. Substitute some theological terms in there and you can get a sense of religion.

The religious practice I understand best is prayer. Prayer as calling, prayer as contemplation, prayer as meditation, prayer as communication, prayer as receiving, as expression. Writing poetry is a form of prayer. I think to Keats’ vale of soul-making – the poem and prayer as force for the world.

Inside of a lot of this, I think, as well, is accepting that not only can’t we understand everything that is going on in the world, and that being in a state of knowing innocence is a good thing, but even more, that in a lot of ways trying to understand the universe, trying to understand every mystery, well, who wants to lose mystery? Who wants every puzzle solved? In the Bhagavad Gita, when Krishna reveals all the great mystery to Arjuna, it overwhelms the warrior and he realizes, no, back off. It’s a little bit like Eliot in the Four Quartets, the bird reminding us that human-kind can’t bear too much reality.

Leslie: Religion has its visionary moments and epiphanies – both small and large. Is that also the case with much of the poetry you read and translate? Can you give examples of these moments from your own work or your translations?

Leslie: Religion has its visionary moments and epiphanies – both small and large. Is that also the case with much of the poetry you read and translate? Can you give examples of these moments from your own work or your translations?

Mark: It’s hard for me to think about poetry that isn’t really visionary. Isn’t William Carlos Williams, with his attention to the daily, as visionary as Whitman? Most poetry I like, even the quietest, seems to me epiphanic because even when there isn’t something brilliant, a bold yes! there is the affirmation of something there in life.

In my own work, well, my most recent book, That Train Again, I feel like there’s one poem after the other that in some ways shows this. That is, my sense of the quotidian as epiphanic.

logos

tightening the stomach

of twisting overlay

of backhand doors

backward doors

trap doors

the opening closing

that becomes descent

or ascent

the world turned upside down

put into the box

any old box

this one came with

the grocery delivery

filled with vegetables bottles, cans

box now taken out to the curb

recycle night

we put newspapers in

that’s the urban

the rural

is the trip to the landfill

or dump

we called it a dump

as in what a dump

which is nowhere to live

though we’ve lived in some

our first Brooklyn apartment

got great light

we strung a hammock

from Mérida across

the big front room

a family hammock

double woven

threaded blue and pink

it sits now in a drawer

unused so many years

muffled street voices

muffled car sounds

what do you do

with these days

that stroll

from morning into afternoon

without interference

sometimes there is a hope

sometimes a prayer

what little music comes in

through the windows

is a fragment of

the music of the world

it was a car passing by

it was some people passing by

it was those clouds

or some kid

who jumped into

what was left on the street

of the puddles from

last night’s rain

now the sun shines

for a second

the sun was in the puddle

but with that one jump

the puddle gone

that’s the picture

right now

a puddle disappeared

by jump and sun

with words left over

to figure how to show

what was

I’ve translated a lot of poetry and I pretty much don’t translate anyone whose work is like my own – if I wanted to write like that I would. I’m best known for Poet in New York, the Lorca translation I did with Pablo Medina, and Black Tulips, which is the selected poems of a Generation of 27 friend of Lorca’s José María Hinojosa who, because of his unfortunate right wing politics, disappeared from Spanish poetry almost until the end of the 20th century. I’m also working right now on Never Made in America, which is selected translations from a wonderful young Uruguayan poet Martín Barea Matttos. That book will be out with my current publisher, Lavender Ink, in Fall 2017.

I’ve translated a lot of poetry and I pretty much don’t translate anyone whose work is like my own – if I wanted to write like that I would. I’m best known for Poet in New York, the Lorca translation I did with Pablo Medina, and Black Tulips, which is the selected poems of a Generation of 27 friend of Lorca’s José María Hinojosa who, because of his unfortunate right wing politics, disappeared from Spanish poetry almost until the end of the 20th century. I’m also working right now on Never Made in America, which is selected translations from a wonderful young Uruguayan poet Martín Barea Matttos. That book will be out with my current publisher, Lavender Ink, in Fall 2017.

Poet in New York is obviously a visionary book – it’s Lorca’s fiercely brilliant response to the city and it really is unlike anything he’d ever written before – it is his greatest poetry. Hinojosa, for different reasons, has a similar kind of development as Lorca – his early work is very much poetry of the country, love poems. But his work grows into a kind of deeper and more religious surrealism – he’s quite good and the marginalization of his work because of his support for the fascists in the Spanish Civil War is one of those awful things that happens. He’s murdered by the left only three days after Lorca is murdered by the right.

Mattos’ s work is original and witty and very political, very left-wing. His poetry is satisfying in many ways, and one of those is that he believes, Ginsberg-like, in the voice of the poet as prophet. There are echoes of the religious that question religion’s connections to capitalism, but, like Ginsberg, like Lorca, he understands religion isn’t precisely something one can avoid.

Wall and Vine

The cloudy day has separated us

like a wall, a blank page

and as soon as it flames a poor flag eclipses

without truce like this post war sun

the cloudy day constructs its wall

and embraces cities new medieval

with its virtual vines it locks us up

don’t look outside don’t look outside

they offer you windows without breeze without spring

the cloud is high like the memory

of fungus of smoke of extinct names

from the industrial smokestacks of history

and the war cry evokes

giant loves that moan

twin defeats

our hearts are like fused

guns the inherited the tense look

that points and shoots

don’t doubt there is no sense there is no debt

nor condemnation if you pray

I give you eternal life, I give.

-Martín Barea Mattos (Mark Statman, translator)

Part two of this interview with Mark Statman about Poetry and Religion will appear in this blog next week.

ABOUT LESLIE TATE’S BOOKS:

I interviewed writer Julia Lee Barclay-Morton about her experience of autism. Julia began as an experimental dramatist in New York, moving to the UK to

I interviewed Gillean McDougall from Glasgow, who edited the collaborative projects Honest Error (on Charles Rennie Mackintosh and his wife Margaret Macdonald) and Writing the

I interviewed French writer Delphine de Vigan, whose book, No et moi, won the prestigious Prix des libraires. Other books of hers have won a clutch

I interviewed Joanne Limburg whose poetry collection Feminismo was shortlisted for the Forward Prize for Best First Collection; another collection, Paraphernalia, was a Poetry Book Society Recommendation. Joanne

I interviewed Katherine Magnoli about The Adventures of KatGirl, her book about a wheelchair heroine, and Katherine’s journey from low self-esteem into authorial/radio success and

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |