SARAH ROSS-THOMPSON AND THE ART OF COLLAGRAPHED PRINTS

I interviewed artist Sarah Ross-Thompson whose exceptional Collagraphed prints use fabrics, lichen, porridge and string to create images of the dramatic Scottish Highlands where she

Jo Young is a modern war poet, shortlisted for the Flambard Poetry Prize, currently researching the subject for a PhD. I asked her about her writing and her views on war as a woman and an army reservist.

Leslie: Can you describe in a nutshell the types of writing you’re involved in and enjoy, please?

Jo: I began writing when I left the Regular Army in 2014 and although I really enjoy writing fiction (and that was my intention), I was drawn into recording some of my military experiences in poetry. During the University of Glasgow’s Creative Writing MLitt programme my fellow writers were extremely encouraging of this and I began to have some small successes with my poems.

Leslie: Some of your poems about army life have a hard, literalist surface, others are intensely metaphorical. How do you approach life in the forces as a reservist, poet and woman?

Jo: I think that to learn something about war helps us to learn something about the world that we live in. I hope to write poetry that opens up unexpected ideas about a woman’s experience of war; the homesickness, how to fight and be a mother, leadership and compassion, and the unexpected nail-bars popping up on battle-torn airfields. For the most part, my poems try to say something about modern war through accessible, everyday observation.

Leslie: Who are your main influences writing about army life? What have you learned from them?

Jo: There is some terrific war poetry being written, especially by women. Just take a look at the recent Bloodaxe publication Home Front, it’s full of the most exquisite women’s war writing. The poetry of US writers and veterans Kevin Powers and Brian Turner has influenced me as has that of the US veteran drone pilot and poet Lynn Hill. Her work in particular tells us about how we come back from war rather than how to go to war and that’s a really vital contribution to understanding the mental trauma of conflict.

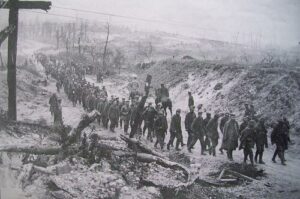

War poetry is a vast canon and I try to bring my 21st century poems into conversation with those that have gone before. David Jones’ In Parenthesis is my touchstone. This WW1 book-length poem is modernist, sprawling, mythical, familiar, lyrical, fragmented and grounded all at the same time. It’s a hybrid form, really, and I handrail it in a lot of my attempts to write. Jones said that he was writing ‘free reflections of people and things remembered, or projected from intimately known possibilities’. I have claimed that as my poetic mission-statement!

War poetry is a vast canon and I try to bring my 21st century poems into conversation with those that have gone before. David Jones’ In Parenthesis is my touchstone. This WW1 book-length poem is modernist, sprawling, mythical, familiar, lyrical, fragmented and grounded all at the same time. It’s a hybrid form, really, and I handrail it in a lot of my attempts to write. Jones said that he was writing ‘free reflections of people and things remembered, or projected from intimately known possibilities’. I have claimed that as my poetic mission-statement!

Leslie: I see you’re an admirer of Mark Doty. What attracts you to his (or other) gay writing?

Jo: I love Mark Doty’s lyricism and invention. He seems to marshal the vastness of beauty and pain and bring it to heel with such precise, sharp imagery. The radishes in Deep Lane for example – I could read that poem every single day and find something new in it each time.

Leslie: What are your key ideas coming out of war poetry and your PhD on the subject?

Jo: War poetry in the 21st Century is rarely written by soldiers and even more rarely written by female soldiers. Much of modern war writing tends to be memoir rather than poetry, or written by observers of conflict (journalists, correspondents, the civilian population or soldiers’ next of kin) but not soldiers themselves. I want to add the female soldier’s voice and explore how women respond creatively to war; to establish a relationship between 21st Century warfare and women’s writing – engaging with topics including mental health, trauma, volunteerism, motherhood, technology, media and geopolitical turbulence.

I am also fascinated with what poetry can teach us about ‘the other’ (or a so-called enemy) and am exploring the motivating use of rich oral poetry traditions by Jihadis. Western war writing has been predominantly individualistic, sorrowful and commemorative and I think there are intriguing or even strategic contrasts to be made.

It’s early days in PhD terms and all these ideas are bouncing around my little brain and occasionally erupting as a finished poem on a page which hopefully makes some of these ideas accessible and fresh to a reader or listener.

Leslie: Do you write about the experience of civilian victims in modern warfare? If yes, how do you approach the subject?

Jo: Yes, I do write about this. It’s hard to avoid the rhetoric of guilt/culpability/denial so I don’t try to. It’s probably quite essential expose those feelings in context, but I am meticulous in not allowing an overt political message to creep in. I am not excusing, explaining or apologising; I simply aim to show. The reader can make her own mind up.

Leslie: How do you find language to describe ‘difficult’ subjects such as war, injury, violence, boredom, fear and betrayal?

Jo: By avoiding the sentimental or hyperbolic and by being rigorous in research. You use the word ‘find’ and that is really appropriate. I often use found text in my poems. I have utilised MoD doctrine pamphlets, the Chilcot Report, contemporaneous WW2 Wehrmachtbericht, eye-witness accounts and rhetoric from present-day interviews amongst other sources.

Leslie: How do you represent heroism and comradeship in the army?

Jo: They are fascinating concepts and understandably elevated in the male tradition. I enjoy challenging these prerogatives as a woman in a patriarchal environment.

Leslie: I’ve asked you a lot of questions about war, but I believe you’re interested in thrillers. What draws you to the genre, given your very real experience of facing danger? Is it a form of escapism?

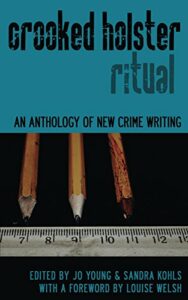

Jo: Yes, it is! I co-edit the Crooked Holster series of crime and thriller anthologies with a fabulous fiction writer called Sandra Kohls. Whilst Sandra can weave amazing crime plots with the best of them, I just enjoy touching the coat-tails of these talented storysmiths. I am so in awe of writers in/around the genre. You are right, a good crime story can press us down with thrill and fear and then plop us back into our real life again. It’s a brilliant gift to their readership. Anyway, Crooked Holster was born from an ambition to bring publication opportunities to to new or emerging crime and thriller writers. We preface each edition with an inspiring foreword from a top crime writer (Andrew Martin, Louise Welsh, Andrew Taylor), who have all demonstrated the generosity and supportiveness of that writing/readership network.

Jo: Yes, it is! I co-edit the Crooked Holster series of crime and thriller anthologies with a fabulous fiction writer called Sandra Kohls. Whilst Sandra can weave amazing crime plots with the best of them, I just enjoy touching the coat-tails of these talented storysmiths. I am so in awe of writers in/around the genre. You are right, a good crime story can press us down with thrill and fear and then plop us back into our real life again. It’s a brilliant gift to their readership. Anyway, Crooked Holster was born from an ambition to bring publication opportunities to to new or emerging crime and thriller writers. We preface each edition with an inspiring foreword from a top crime writer (Andrew Martin, Louise Welsh, Andrew Taylor), who have all demonstrated the generosity and supportiveness of that writing/readership network.

Anna

I bought the book for a pound

from an old shop with Chesterfield sofas

in a neatly folded Cotswold town.

Quietly pleased with how

high-brow she made my shelves look,

I kept her on view in the kitchen – uncreased.

Vengeance is mine said the first page

I knew she was going to need concentration.

Finally I unfolded her on a hot day in Helmand,

and imagined a symmetry in the deadly pirouettes

which our homelands, mine and hers

were still grinding in the sallow soil,

wearing those red shoes

which do not allow the dancers to stop

unless they hack their ankles off –

(which neither side were about to do in 1878

and ever since, we’ve followed suit).

Me, her and a hard folding chair,

in the mineral air with dust at times as soft

as champagne mousse or a sable shrug

and otherwise – savage as crushed marble.

I would arrive for work

with my cheeks streaked

from a horse’s death

or the stress of being parted

from a child I had not yet met.

When the last page closed,

a dull fifty pages after she threw away her red bag,

I tucked her deep in the book-swap box

in the female shower block.

I suppose I didn’t want to share.

Days later, I still felt her,

laying my face fully across the chill outlet

of the air conditioning unit

and pressing my body against the hard, steel rail of my cot.

I looked for a swoop of beauty in that place,

the unquestionable meaning of goodness

I found vengeance and a queer grace,

dismantling of time and amendment

pocked with a suicide cough in ricochet.

Jo Young

| Jo Young writes:

The poem is a personal recollection of reading Anna Karenina whilst in Afghanistan. There are large amounts of routine and boredom inherent in war and this has often been documented. Modern soldiers counteract it by reading, watching box sets (also a feature in some of my poems!), setting learning goals and exercising. I spent a month reading Anna in the evenings and it was a narrative I couldn’t get out of my head. I was also reading a lot of history books about previous Afghan wars (British, Russian and Soviet) and felt a strong mapping of parallels, repetition and a weariness about the struggle to dominate that |

terrain and culture which was still happening almost a century and a half later. The violence in Anna comes to us through a female viewpoint: her suicide I see as a lying-down more than anything else. I was trying to capture a sense of that, heightened by the experience of being in a strange and arduous environment. I was also trying to capture the moment when I realised what a tiny piece of history we all were in – such a mighty theatre of war – and feeling, for the moment, the helplessness of it. |

In this next week’s guest blog, international poet and translator MARK STATMAN describes his move from the USA to Mexico and his feelings about President Trump’s election.

ABOUT LESLIE TATE’S BOOKS:

I interviewed artist Sarah Ross-Thompson whose exceptional Collagraphed prints use fabrics, lichen, porridge and string to create images of the dramatic Scottish Highlands where she

Part 2 of my interview with Mark Statman looks closely at Mark’s Latin American poetic influences, his life in Mexico and ends with an extract

I interviewed international poet and translator Mark Statman about Volverse/Volver, his 14th published collection. Mark, who has won national arts awards, is Emeritus Professor of Literary

I interviewed Lisa Dart, finalist in the Grolier, Aesthetica and Troubadour Poetry Prizes and author of The Linguistics of Light (poems, Salt, 2008), Fathom (prose

I interviewed writer Julia Lee Barclay-Morton about her experience of autism. Julia began as an experimental dramatist in New York, moving to the UK to

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

8 responses

A lovely post, Leslie. I have a fair collection of poetry from WWI and WWII. I buy them on my infrequent trips to the UK. I also read local poetry about the Anglo boer war. War poetry is very intense!

Thank you, Robbie. It’s a subject that rarely gets a woman’s point of view – but that’s changing, I think.

Wonderful post.

Thank you Linda!

Very nice piece Leslie, refreshing perspective and many points to reflect on; as ever, in response to your searching questions; thank you!

I’m glad you enjoyed it, Chrys. 🙂 🙂 🙂

I really enjoyed that interview, and Jo’s poem as well. I was lucky enough to do my MLitt alongside Jo and found her work both inspiring and challenging to read. I’m pleased to see that she has continued to explore the role of women in war. Thanks for this!

Thanks Kendra, I guessed you must know Jo already! 🙂