Part 2 MARK STATMAN: MEXICO AND THE POETRY OF GRIEF AND CELEBRATION

Part 2 of my interview with Mark Statman looks closely at Mark’s Latin American poetic influences, his life in Mexico and ends with an extract

I grew up in the Fifties wanting to be a spiritual child. I didn’t see grand visions or hear strange voices and my world was small, measured by school times and mealtimes and trips to see the family. But in private spots and in places I visited there was a pictorial quality, a sense of something extra, an additional factor that filtered in, making for significance. It was visible but elusive, an edge to experience unnoticed by anyone else, like a signal from a distance that doesn’t transmit and yet somehow registers. I was witness to impressions that couldn’t be named.

But being spiritual didn’t come easily. Religious Education was boring and closing your eyes in school assemblies was considered a sign of weakness, so the head-down lads would pull monkey faces and wink at each other. They teased boys like me as odd or airy-fairy. Given their persistence and the widespread adult reluctance to discuss ‘personal matters’ it was surprising that I held onto my spirituality at all. My parents thought of themselves as reasonable, down-to-earth people who viewed prayers as slightly suspect and congregations as stand-offish, so going to church was Christmas-time-only. I think the war had interrupted regular worship, there was a reaction against rationing or ‘making-do’, and as belief waned, people wanted gadgets not God.

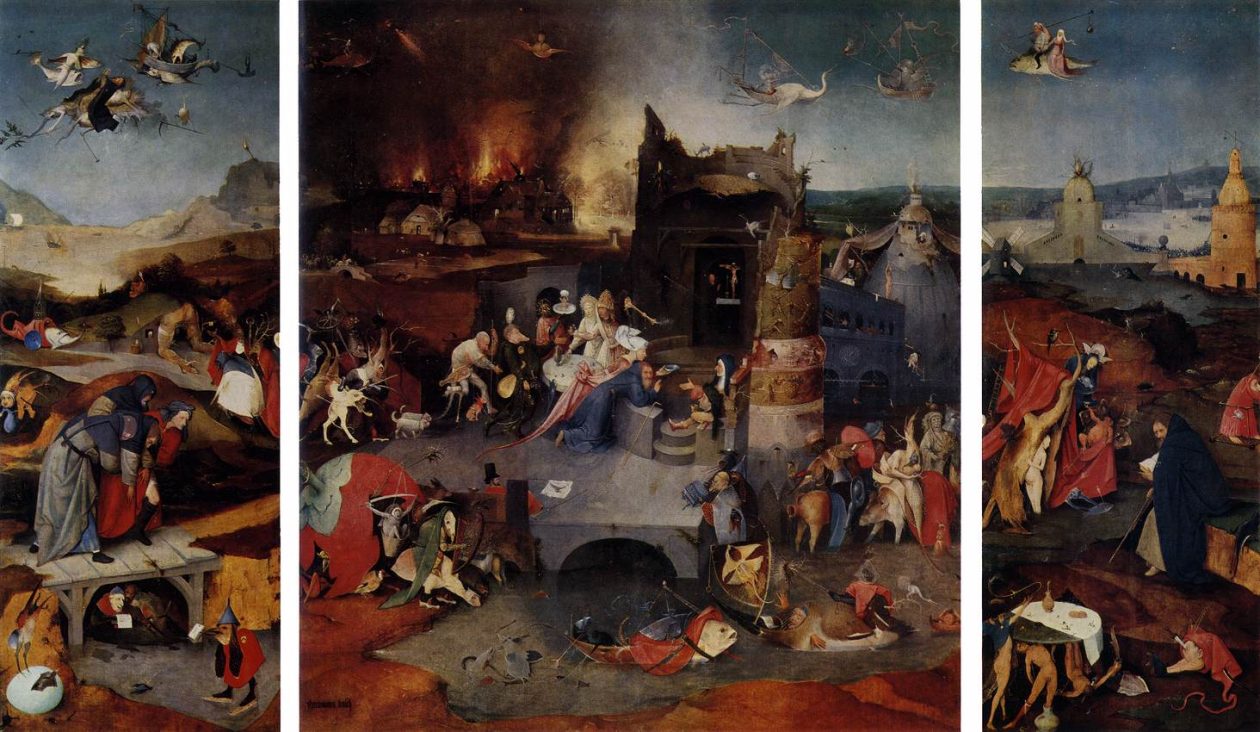

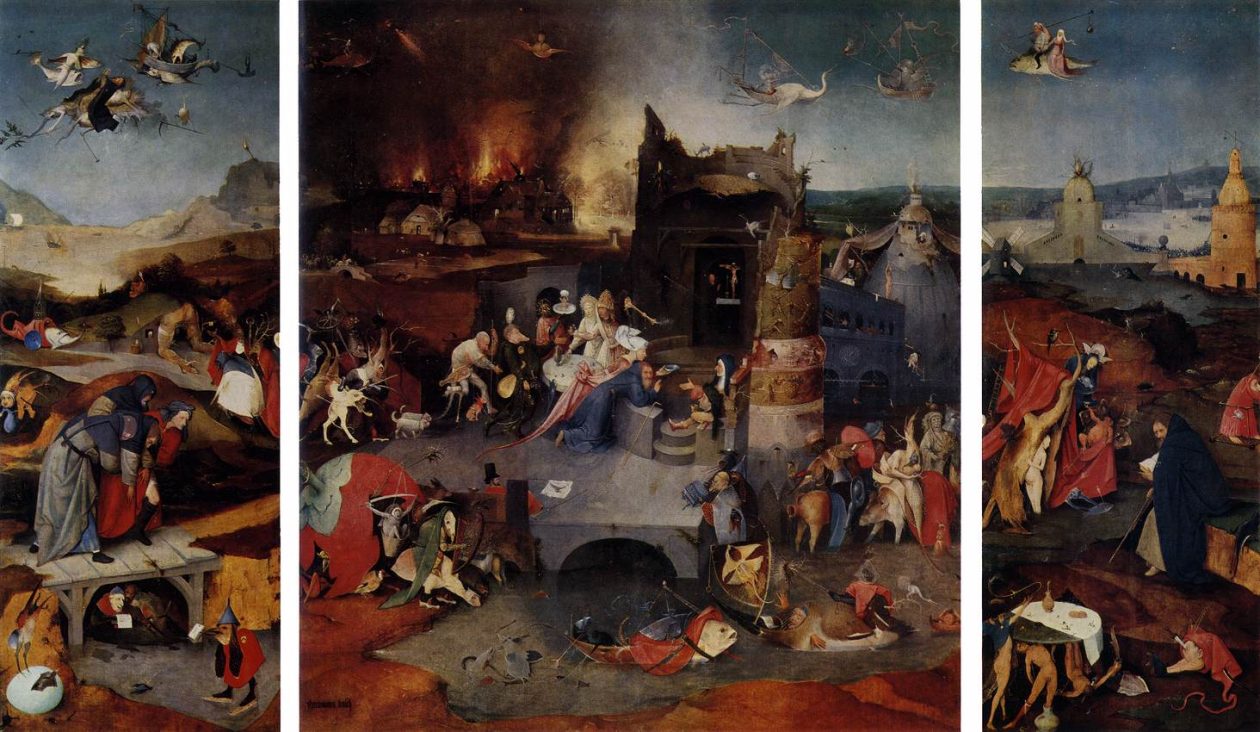

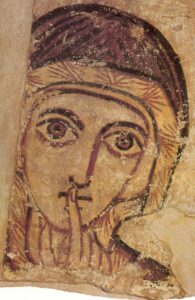

My spirituality was untutored, expressing itself in vague longings in parks and gardens and a love of music. I found patterns in brick, secret messages in worm casts and ant runs, and moments of immersion in the change of seasons. On holiday, the wind on the seafront moved me while the view out to sea filled me with breathless excitement. And to keep up my high I began, as I got older, to take myself off on long country walks quoting Wordsworth in my head – and sometimes out loud – searching for uplift. The hypnotic rhythm of my steps filled my thoughts as I worked at being spiritual, driving my feelings to be wild and strange and mystically inspired. I fed my moods, imitating Richard Jefferies in The Story of my Heart with his cultivated intensity and longing for ‘soul-life’. Still later, I came to see myself as a mediaeval mystic, cut off from life, experiencing visions similar to the Temptation of St Anthony, feeling haunted and hunted and spiritually exposed. I wanted to be a poet so I looked for signs – the exact angle of a broken fence, a skyline, a flower, stones in water – and I made myself sensitive, directing my attention to memorising every detail with a straining, urgent need for elevation. I wrestled alone with my angel. And yet, nothing seemed to change. I wasn’t saved or inspired or lifted out of myself. I remained time-limited and vulnerable. And the poetry I wrote was embarrassing.

The obvious conclusion was that my spirituality had to be forced because it wasn’t authentic. In a sense I was trying to bully myself – or, as my parents might have said, ‘getting above myself’ – straining to realise ‘the other’ as a concrete, graspable, here-and-now experience. I’d not understood metaphor or symbol and still believed a spade was a spade was a spade. As a result my faith was attempting to move mountains. In any case, from a Buddhist perspective, my longing for ‘spiritual experience’ introduced a false split between ‘experiencer’ and ‘experienced’. Rather than simply being I was trapped within false opposites.

At the same time, the youth I was becoming pooh-poohed it all. I had another, rather sneery voice telling my spiritual child to be quiet, that the film he was running in his head was a projection of his own fear and self-importance – a view I embraced later when I read Freud’s ideas on religion. I came to see my spiritual boy as a neurotic illusionist trying to boost himself with a few cheap tricks. He was in the grip of superstition and his need for a sign was a child asking for the impossible.

But putting the spiritual behind me left a gap. I tried to fill it with Marxism but the behaviour of its followers put me off. Later I adopted Existentialism’s notion of conditional belief as a deliberate choice, but it left me feeling empty. Without warmth or transport life was flat. It was better to strain and be pumped-up than to walk away – and the path I was avoiding was the hard slog back to the crazy poetry-boy and his fight with the angel.

So the romantic but self-aware believer is still part of me. His transports are mine, now realised in the certainty of doubt, the via negativa and the silence. I don’t need miracles, just deepened understanding. And it’s in remembering my absurd flights of fancy as the spiritual child – that wide-eyed, speculative and contradictory state of being where the world is charged with something additional – that I now find God.

(This passage is an extract from my ‘Imaginary Autobiography’ Heaven’s Rage – more details below.)

ABOUT LESLIE TATE’S BOOKS:

In next week’s interview, THE WONDERFUL WORLD OF ILLUSTRATING CHILDREN’S BOOKS, I asked Hannah Marks what has inspired her own, very distinctive style of illustration.

Part 2 of my interview with Mark Statman looks closely at Mark’s Latin American poetic influences, his life in Mexico and ends with an extract

I interviewed international poet and translator Mark Statman about Volverse/Volver, his 14th published collection. Mark, who has won national arts awards, is Emeritus Professor of Literary

I interviewed Lisa Dart, finalist in the Grolier, Aesthetica and Troubadour Poetry Prizes and author of The Linguistics of Light (poems, Salt, 2008), Fathom (prose

I interviewed writer Julia Lee Barclay-Morton about her experience of autism. Julia began as an experimental dramatist in New York, moving to the UK to

I interviewed Gillean McDougall from Glasgow, who edited the collaborative projects Honest Error (on Charles Rennie Mackintosh and his wife Margaret Macdonald) and Writing the

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

6 responses

A beautiful post, Leslie. Have a wonderful Easter break (however you celebrate).

That’s very kind of you! Sue and I will go to a hear Methodist preacher on Good Friday and on Sunday we’re going to an Indian wedding.

Very moving and inspiring post, especially for this day and this world at the present time.

Thank you Karen, that’s very kind of you! 🙂

This is a lovely, lyrical post.

Many readers will recognise themselves in your journey.

While you wrestled with your angel, many of us also experienced the same seeking, the same longing, the same, ineffable sense of the numinous; a wanting of something transcendant, immersive, boundless, enveloping.

I was immediately struck by your reference to the “false split between ‘experiencer’ and ‘experienced’” that left you “trapped within false opposites”, and which was part of your earlier spiritual struggle.

Such striking words. It feels like they could be the transparency film that’s laid over your life’s journey so far: coming to terms with being whole and undivided.

Thank you for this, Leslie.

Happy Easter!

Wow! I’m so glad you’re coming onto my blog on May 29th, Michelle. A beautiful comment.