JANE BURN – POETRY AS HARD GRAFT, INSPIRATION, REACTION OR EXPERIMENT?

I interviewed poet & artist Jane Burn who won the Michael Marks Environmental Poet of the Year 2023-24 with A Thousand Miles from the Sea.

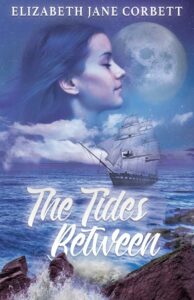

I interviewed Elizabeth Jane Corbett, who won the Bristol Short Story Prize and was shortlisted for the Allan Marshall Short Story Award. Elizabeth lives in Australia, where she teaches Welsh, is an author and librarian, and writes articles for the Historical Novel Review and blogs at elizabethjanecorbett.com. Elizabeth says about herself: “I live with my husband, Andrew, in a renovated timber cottage in Melbourne’s inner-north and I like red shoes, dark chocolate, commuter cycling, and reading quirky, character driven novels set once-upon-a-time in lands far away.” Elizabeth’s debut novel The Tides Between , shortlisted for the HarperCollins Varuna Manuscript Development Award, is published by Odyssey Books.

Leslie: Can you tell us in a nutshell about your young adult historical novel The Tides Between, please?

Elizabeth: The Tides Between is being marketed as a YA novel and it would certainly be suitable for young adults. However, it is not simply about growing up. It is about losing faith in the stories by which you have made sense of life, and learning to read them with different eyes. It is also about mental illness, blended families, and facing difficult truths. I therefore see it as a book for all ages.

Leslie: Can you describe the writing process that went into your novel?

Elizabeth: Writing The Tides Between has been a torturous process – my first attempt at writing fiction since a truly deplorable short story in year eleven. I wasn’t sure if I was capable of writing a novel. But I’d always wanted to try. Turning forty proved to be the catalyst. I thought if I don’t start soon, it will be too late. But what to write about? I had no idea. I simply picked a topic that interested me (nineteenth century immigration to Australia), and started reading. To my immense surprise, characters began forming in my head. I had no understanding of viewpoint, voice, or character development. But I set out to write a historical saga spanning several years. I also sensed that if I read too many how-to-write-novel books I’d be too scared to start. I decided to simply put my characters on a ship and see what happened. It turned out my main character was a fifteen-year-old girl, called Bridie, who’d lost her father in tragic circumstances. She is befriended by Rhys Bevan, a young Welsh storyteller. But Rhys had secrets. And taking refuge in fairy tales was not the easy answer Bridie envisaged. Somewhere around the Canary Islands, I faced a decision. Did I keep trying to write the saga I had initially envisaged? Or tell the story that was unfolding. I chose the latter, reasoning it was a practice novel, unlikely to ever find a publisher.

Leslie: What major changes occurred as the script for The Tides Between turned into a published novel?

Elizabeth: I joined a writing group once I had a full manuscript under my belt and, through working with other writers, learned about a mentorship program being offered by Varuna, a writing centre in the Blue Mountains. I submitted The Tides Between under its working title Chrysalis. To my immense surprise the manuscript was shortlisted. So, maybe I could write? My application didn’t lead to a mentorship. But a paid manuscript assessor suggested I learn about story structure. I therefore booked myself into a novel writing subject at our local TAFE (technical and further education) college. In the end, I re-wrote The Tides Between several times.

At some point, it dawned on me that I had written an unusual novel. A historical coming-of-age novel, with both adult and young adult viewpoint characters, that included embedded Welsh stories and elements of magic. I had no idea about where to put it on the ‘bookshop shelf.’ The publishing industry is so market driven. My novel simply didn’t fit neatly into a category. I submitted it to major publishers, with little success. But I had quite strong interest from small presses. It seemed they were more willing to take a risk. I eventually signed with Odyssey Books.

Leslie: How did your novel grow and develop during the writing process?

Elizabeth: My characters are all fictitious. But they grew out of my research. As I learned about the nineteenth century emigration system – the voyage, the ships, the routes those ships travelled, the embarkation process, shipboard rules and routines, the rations they received, the illnesses they suffered en route, the situation on arrival in Port Phillip Bay – my characters began to emerge. So, for me, research comes first, then character. I’ve been told I am a psychological novelist. The inner development of my characters drives the story. But I value the insights of my plot-driven writing buddies. It makes my work stronger.

Leslie: Did you absorb all your research first and write freely then edit for accuracy afterwards, or were you constantly referring to your historical notes while composing?

Elizabeth: I made copious notes during the research phase, to cement things into my mind. I also checked up on facts as I wrote. I am not sure whether this is efficient. But it seems to be part of my process. I often find metaphors and similes come out of the realities of a situation – the sea, the seasons, the ceremonies, therefore just banging words onto the page without checking doesn’t work for me. However, once the first draft was written, I entered a second research phase. This meant more in-depth reading about the embarkation process. I made my first I-am-writing-a-novel approach to an academic at this stage and completely re-wrote the early chapters as a consequence. A second manuscript assessor pointed out that the novel was starting too slowly. I needed to lose a few thousand words from the beginning. I therefore condensed the new material. However, what I arrived at was informed by things I’d discovered in writing the longer version. So, it wasn’t wasted. For me, writing is very much a trial and error process.

Leslie: Which historical novelists do you admire – why them?

Elizabeth: Dorothy Dunnett’s work introduced me to an online writing community before the days of social media. Edith Pargetter introduced me to the last Princes of Gwynedd. Brother Cadfael was my first encounter with a fictitious Welsh character. Sharon K Penman’s work built on this. How Green was my Valley was my first taste of a Welsh Valleys narrative voice. I also like Kate Forsyth, Emma Donoghue, Diana Gabaldon, Kate Morton. Mostly women writers, actually. Though, I did enjoy Bernard Cornwell’s Saxon series.

Leslie: Is the modern historical novel a factually-accurate recreation of an era or is it closer to language-led and character-driven modern fiction?

Elizabeth: I’ve heard it said of Shakespeare’s historical plays that you learn a little about the era in which they are set, a little more about Elizabethan England and a great deal more about the human heart. I believe it is true of all good historical fiction. We write out of our consciousness for people living in our times. We do our best to not make our characters non-anachronistic. Or, at least, to convince our readers that they are in sync with the setting of the novel. However, if we tackle universal themes then the work transcends the zeitgeist of our age and the era in which it is set. Which is the ultimate in my opinion.

Elizabeth: I’ve heard it said of Shakespeare’s historical plays that you learn a little about the era in which they are set, a little more about Elizabethan England and a great deal more about the human heart. I believe it is true of all good historical fiction. We write out of our consciousness for people living in our times. We do our best to not make our characters non-anachronistic. Or, at least, to convince our readers that they are in sync with the setting of the novel. However, if we tackle universal themes then the work transcends the zeitgeist of our age and the era in which it is set. Which is the ultimate in my opinion.

Leslie: Could you break your life experience down into sections, please, describing the key people, places and incidents that have turned you into:

Elizabeth: I was born in England to an English father and a Welsh mother. My family emigrated to Australia when I was five years of age. However, I wasn’t allowed to tell people I was English. I was British, Mum insisted. This was her way of saying Welsh is not the same as being English. However, my dad always rolled his eyes when she said this, as if being Welsh was somehow ridiculous. This was my first experience of cultural prejudice. However, both parents were pretty proud to be from the UK. Our family were not like those other ‘lesser’ European migrants who had to be ‘naturalised.’ So, there was more than a little Anglo/Welsh superiority in my upbringing.

My university years challenged this perspective. But it wasn’t until I moved to Fiji and saw indigenous communities living on their traditional lands that I began to understand what the indigenous peoples of Australia had lost. We visited other Pacific islands while living in Fiji. Became part of an international community through the school my kids attended. After returning to Australia, one of my children participated in an AFS student exchange program. Student exchange is all about language learning and cultural respect. We enjoyed hosting three girls in return – one from Holland, one from the Faroe Islands and one from Switzerland. Re-connecting with my Welsh heritage was the next stage in my evolution. I learned of Wales’ conquest, deliberate attempts to eradicate the Welsh language, their even-now struggle for self-determination. The scales fell from my eyes. Colonialism was violent and greedy. Immoral. For the modern person, it should be painfully obvious. But not so long ago, I heard a man say Australia’s indigenous people needed to be civilised. If civilisation meant stealing their land, raping their women, poisoning their waterholes, hunting them like beasts, and forcibly removing their children, then I say Australia’s indigenous people could have done without the experience.

2. An Australian ‘questioner of everything’ (including yourself)?

Elizabeth: I think I might have just been born this way. It is a gift, I suppose? But not always a comfortable one.

3. An exile who has found her home in the Welsh language, mythology and culture?

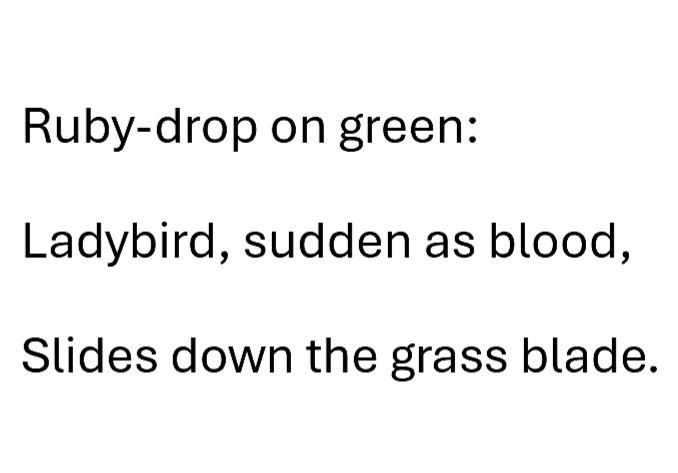

Elizabeth: Learning Welsh has alleviated the sense of hiraeth – a poignant longing for a home that goes beyond homesickness – that I have felt for my entire life. Would I have felt that longing if I’d grown up in England? Or indeed Wales? Maybe hiraeth is simply a yearning for something more? However, when I first encountered Cymraeg, something shifted inside me. Its words were so evocative. Llosg fynnydd (volcano) literally means burnt mountain, and a skunk is a drewgi – literally a stink dog. A Corgi is a dwarf dog. The term for ladybird is Buwch Goch Gota – short red cow. A butterfly is a pilipala. You can almost hear wings fluttering! In South Wales, owl is called a Gwdihŵ, which is so wonderfully onomatopoeic.

I never expected to actually speak Cymraeg. I’d been rubbish at languages in school. But I happily anticipated a lifetime exploring the meaning and sounds of individual words. Then we went through a difficult stage with one of our children – running away, self-harm, police convictions, drugs etc. I took it pretty hard, felt like I’d failed as a mother (never mind that the three others were doing just fine). My husband said I needed to get away. We had heaps of frequent flyer points. So, I booked a trip to Wales. In preparation, I did the online Say Something in Welsh course. It is an audio course – so podcasts. At the end of each lesson, Aran, the tutor told me I was doing a great job. That I would succeed. Every lesson – great job, well done, you can do it! His words were like rain on parched earth. I literally walked through that time holding onto the tail of an ancient language. So, in one sense learning Welsh saved me. It certainly expanded my soul. I am a different person when I speak Cymraeg. A fuller, more vital version of Elizabeth Jane Corbett. Perhaps, the one I was meant to be all along. If not for imperialism…

Leslie: Finally, what did you get out of writing The Tides Between – what do you hope a reader will get out of it?

Elizabeth: I set out to write a pioneer saga and ended up writing a coming-of-age novel that is set entirely on board a nineteenth century emigrant vessel. This is partly because of the type of writer I am (I didn’t know I was a psychological writer when I started out) and partly because I decided on the spur of the moment to throw a couple of Welsh characters into the mix. Mum was Welsh but I knew very little about Wales prior to writing The Tides Between. Doing a ‘spot of research’ on the Welsh language (Cymraeg) turned into a love affair. I had no idea the Welsh language was so beautiful. That Wales had such a rich bardic heritage. Or that its history was so brave and strong and interesting. The Welsh elements took over my narrative as they have my life. I now tutor others in Cymraeg. So, if people glimpse something of that beauty, I will be happy.

The Tides Between is also about sacred stories. I came to faith in an evangelical Christian tradition during my teens. A tradition that emphasises a fairly literal understanding of scripture. The trouble is I’m a thinker and the older I got the harder it was to conform to simplistic understandings. So, when my Welsh character Rhys says to fifteen-year-old Bridie, “Painful, it is, when the words that once brought comfort, seem to lose their voice. It’s not the stories that are at fault. Or that we were foolish to believe. Only that we must learn to see with different eyes.” I am reaching deep into my own experience. I didn’t realise this when writing, only afterwards on reflection. But I guess, The Tides Between is a novel for people who are trying to find new ways to make sense of their sacred stories. Bridie’s eventual realisation: “there were no easy answers, only love and people who were complex.” Is about where I am at now. It’s taken me fifty years to get to that understanding. If I can help someone else reach that point, I will have done my job.

Next week, in WELSH-ENGLISH POET WITH ONE FOOT IN NEW ORLEANS, I interview multi-talented Welsh writer, dancer and musical performer clare e. potter.

ABOUT LESLIE TATE’S BOOKS:

I interviewed poet & artist Jane Burn who won the Michael Marks Environmental Poet of the Year 2023-24 with A Thousand Miles from the Sea.

I interviewed ex-broadcaster and poet Polly Oliver about oral and visual poetry, her compositional methods, and learning the Welsh language. Polly says, “I absolutely love

I interviewed Jo Howell who says about herself: “I’ve been a professional photographic artist since I left Uni in 2009. I am a cyanotype specialist.

Poet Tracey Rhys, writer of Teaching a Bird to Sing and winner of the Poetry Archive’s video competition reviews Ways To Be Equally Human. Tracey,

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

6 responses

I have found this interview quite fascinating Elizabeth. I am from the Welsh valleys, my father was Welsh, I lived in South Wales for eighteen months but following my father’s death, my mother, a Romany traveller moved back to Middlesex. I too have felt that deep longing for something that cannot be put into words. I love the way that you have embraced your ancestry and true belonging. I look forward to reading your novel. I wish you well.

Thanks for reading Raine and for taking the time to comment. I hope you too have found somewhere to call home?

You’re welcome. I am hoping to move to the Malvern Hills next year, on the borders of Worcestershire and Herefordshire. From West Malvern you can see the Welsh mountains. Its a stunning place. Good luck with your work and life or as the Romany people say, Kushtie Bok.

A very interesting interview, Elizabeth and Leslie. This book sounds very unique.

Thank you, Robbie. USP indeed. 🙂 🙂 🙂

Bora da!

Welsh mother, Scots Irish father, grew up in Geneva, Switzerland after WWII spent in Manchester area, and now live in the U.S.A. Was evacuated to Wales during

WWII and sometimes also feel ‘hiraeth’… thank you and Du Bendyddio!