SARAH ROSS-THOMPSON AND THE ART OF COLLAGRAPHED PRINTS

I interviewed artist Sarah Ross-Thompson whose exceptional Collagraphed prints use fabrics, lichen, porridge and string to create images of the dramatic Scottish Highlands where she

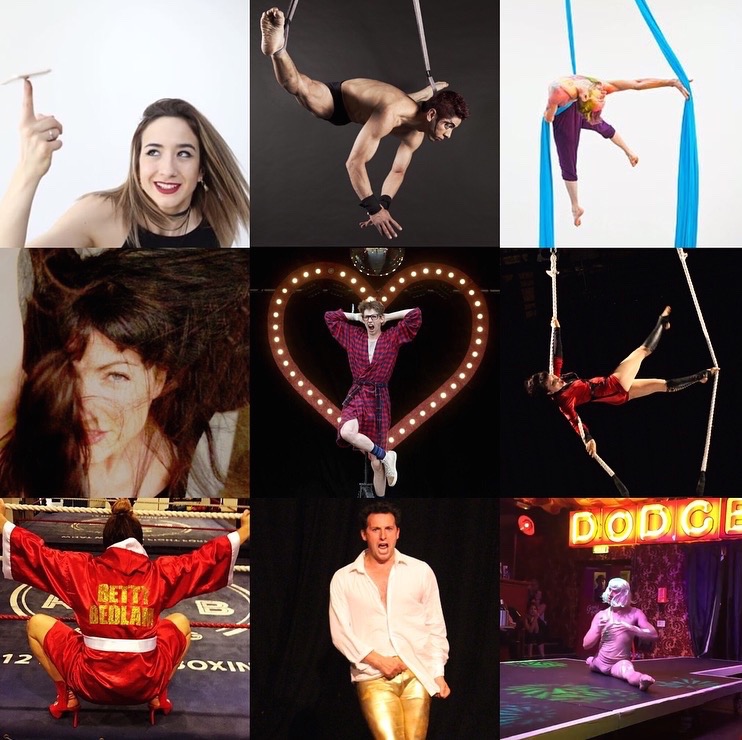

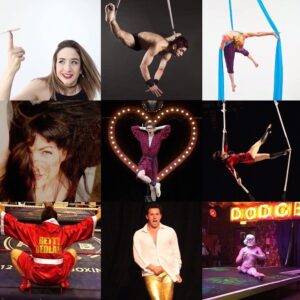

In part two of my interview with Lucy Van Hove about theatre-circus, I asked her to share what she’s learned from training for contemporary circus as well as her personal recommendations for shows to watch.

Leslie: What circus acts do you perform yourself? What drives you to do them? What are the personal difficulties and rewards of this kind of work?

Lucy: I’m very much an amateur, learning a bit of everything, a Jill of all trades, mistress of none. What drives me? A love of fun and stepping outside of my comfort zone. The challenge more often than not is mental rather than physical – as a student I have complete faith in my teachers pushing me, but never beyond my capabilities. Sometimes, though, it is a real struggle to get my brain to send that message to the rest of my body! Time and again, the reward is gaining confidence, resilience and strength.

My first love is aerial and that sensation of my stomach turning inside out. In fact, it was the draw of the flying trapeze that originally led me to sign up to circus skills classes at the National Circus in Hoxton. From there I discovered a whole new world of aerial disciplines that do not necessarily fly around as much – like static trapeze, aerial hoop (lyra), rope and silks – and as a result enable subtler, gentle movement to be woven between dramatic tricks. This enables the performer to construct a physical language that can work as aerial ballet or as part of a theatrical narrative, which appeals to the storyteller in me.

To improve my balance, I also took several equilibristics courses at the National Circus, (attempting!) to learn unicycle, tightwire, rolla-bolla, and globe walking, and now have my own practice tightwire at home. I love the wire as a discipline as it requires full concentration and staying present in the moment. It is very zen, and deeply calming.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=1&v=ILZ_KfMvPm0

Also very zen, and probably the most dramatic skill I’ve practiced – gauging people’s reactions to my training video! – was body-burning and eating flames during a two hour workshop at The Fire School with Red Sarah. It really was trial by fire, and I never expected to learn so much in such a short space of time, nor find it such a primordial, and rewarding, experience.

Juggling has been a revelation on this circus journey. At university I was part of the juggling society, and pretty hopeless. Three balls was, and still is, pretty much my limit, although I have learned a few more tricks along the way thanks to juggler Jon Udry. Then a few years ago we went to Camp Bestival with friends and saw Gandini Juggling perform mesmerising sequences en masse and with LED clubs that choreographed in synch to the music. It was great fun and since then I’ve seen more of their outdoor pieces at festivals, but it is their ground-breaking, experimental work that I’ve seen on stage at Jacksons Lane theatre (Meta), incubator of the contemporary circus scene, the Royal Opera House (4×4 Ephimeral Architectures), Sadlers Wells (Smashed) and the English National Opera (in Philip Glass’s opera Akhnaten), that have moved me beyond words.

The gift of laughter connects an audience in a wonderful way, and watching real clowns at work is a sheer delight for me, whether in a big top with the likes of Giffords Circus’s Tweedie the Clown, who with a quiff of red hair and without a trace of white paint is accessible to all, to Cirque de Soleil clown Sean Kempton in his own solo show ‘Stuff‘.

I have been to a few clowning workshops myself, which leaves me in further awe of those who clown around professionally. First with Jorge Costa, an Argentine Charlie Chaplin, in tango with his wife Julia Muzio, and then with Cirque de Soleil and Slava’s Snowshow clown Ira Seidenstein. I have to say slapstick is the hardest, and most painful, lesson of all. Learning how to expose your vulnerability and make a joke of it is an excruciating process. So, to celebrate my 40th, I ended up at the Slapstick Festival in Bristol with Ken Dodd throwing a custard pie in my face. Probably the most surreal and ridiculous encounter ever!

Leslie: Can you pick out a few of your favourite acts, summarising what they do and explaining why they are important?

Lucy: It is hard to pick out a few when I have written over 200 posts about different artists and companies! Here though are a few examples of what I like and why, just to give a sense of the sheer variety on offer:

A few years ago Finnish aerial artist Ilona Jäntti performed an aerial piece in Highgate woods outside Jacksons Lane with maybe a dozen people in the audience. It was bitterly cold, and yet in jeans and DMs she spun out an aerial sequence on ropes that was entirely natural and other-worldly.

Barely Methodical Troupe are like the boy band of circus and so much fun. Bromance was their first show, a funny, touching trio exploring the dynamics of male friendship. It was at the Edinburgh Fringe where I first saw the Cyr wheel, with the artist (in this case the aptly named Charlie Wheeller) spinning round like Vitruvian Man. I saw Barely Methodical Troupe again recently in an expanded cast, opening at Worthing Theatre’s six week summer of circus with Kin, riffing a Britain’s Got Talent scenario, with humour on a par with their phenomenal skill, and female acrobat Nikki Rummer more than holding her own in the wolf pack. Then there is the female trio Alula Cyr performing Hyena on the Southbank this summer, spinning as one on the same wheel – a great moment for the sisterhood.

Zippo’s big top extravaganza Cirque Beserk, which I saw at Sadlers Wells, gave me the most terrifying fright. It was when the artist on the wheel of death – imagine two hamster wheels rotating on a pendulum – stood atop, on the outside of the wheel, without a safety harness, blindfolded, on stilts and skipping on a rope. I’m not sure if I enjoyed watching it exactly, but it was certainly an impressive feat!

Amici Dance Company staged Tightrope at the Hammersmith Lyric last summer in an anniversary production that included artists from Ockham’s Razor and Joli Vyann working with performers of mixed abilities to tell the story about a dilapidated circus struggling to survive. One of the most exhilarating moments for me was seeing Suzy, a dancer who, when I saw her a couple of years ago, could not get out of a wheelchair unsupported, deftly execute a whole sequence of moves in duet on trapeze with such grace that it defied words as much as expectations. The show was a funny, touching, and a glorious razzmatazz that kept my children engrossed from start to finish and embraced the philosophy that in this crazy world at the end of the day, whatever our gifts and our challenges, we are all in this together.

Leslie: How do circus performers deal with injury and ageing? Are there other similarities to high-performance sport?

Lucy: A few years ago I went to a pole dancing workshop run by Cirque de Soleil artist Felix Kane. The year before she had a bad fall in a show in Vegas and nearly died, and her shoulder was still giving her problems, but as well as guiding us through moves at the last minute she decided to give an impromptu spin for us, set to Lana Del Rey’s ‘Born To Die‘. The shudders she gave on the pole and the extraordinary range of movement brought home the sheer wonder and fragility of life. I still get goosebumps thinking of her courage and generosity of spirit sharing that.

If you check out any student or performer’s Instagram account, #circushurts is a common refrain. Welts, bruises and callouses from rope burn, toe hangs and slip-ups are part and parcel of everyday life and resilience builds up over time. Injuries do happen. Not many in my case, as I tend to be innately cautious, but the ones I have had resulted either from over-tiredness, losing concentration or over-ambition. That’s just part of the learning process, even if it means falling flat on your face. As I was told when learning to ice-skate: if you don’t fall, you aren’t stretching yourself and you will never progress. Professional performers are curious about ‘what happens if I do this…’ and are constantly pushing themselves to new heights, increasing the risk of injury, but the result on stage is worth every fall. I think, like the Roman circus, the public demands an element of danger in order be thrilled. It’s brutal like that.

On the other hand, although the physical demands of circus are second to none, it can be more forgiving than a high-performance sport, as it is an art. What I mean by that is that technical precision is important, but so too is stage presence and charisma. As long as they have that, I believe artists have a longer shelf-life than athletes, and that is a draw for a number of former gymnasts. I do see performers working out their exit plans, and often a natural progression from performing will be teaching or creating/directing shows instead.

Leslie: What are the most important contributions circus has made to imaginative life, and what does it teach us about the human condition?

Lucy: Circus has long since been a muse as much as amusing artists, writers, musicians, fashion from Bowie to Vivienne Westwood, Matisse to Erin Morgenstern (The Night Circus) and Katherine Dunn (Geek Love). It inspires us to be the best possible version of ourselves and dares us to dreams, while also recognising the darker side of human nature, accepting, if not reveling, in the grotesque.

Traditional circuses are there to provide entertainment and escapism, to thrill the audience, encourage them to sigh, love and laugh.

Traditional circuses are there to provide entertainment and escapism, to thrill the audience, encourage them to sigh, love and laugh.

Contemporary circus can engage in this way, but also it uses the body to explore and challenge boundaries, whether physical, gendered or political. And in cross-fertilising with different art forms, primarily dance or theatre, it is developing a radically different semiotics of performance, offering new possibilities for expression and continually evolving. These are exciting times.

Next week I interview Jane Davis, winner of the Daily Mail First Novel Award 2008 and whose 2015 novel, An Unknown Woman, was Writing Magazine’s Self-published Book of the Year.

ABOUT LESLIE TATE’S BOOKS:

I interviewed artist Sarah Ross-Thompson whose exceptional Collagraphed prints use fabrics, lichen, porridge and string to create images of the dramatic Scottish Highlands where she

Part 2 of my interview with Mark Statman looks closely at Mark’s Latin American poetic influences, his life in Mexico and ends with an extract

I interviewed international poet and translator Mark Statman about Volverse/Volver, his 14th published collection. Mark, who has won national arts awards, is Emeritus Professor of Literary

I interviewed Lisa Dart, finalist in the Grolier, Aesthetica and Troubadour Poetry Prizes and author of The Linguistics of Light (poems, Salt, 2008), Fathom (prose

I interviewed writer Julia Lee Barclay-Morton about her experience of autism. Julia began as an experimental dramatist in New York, moving to the UK to

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

4 responses

Great interview and such an interesting career.. thanks to both of you.

I’m glad you enjoyed it, Sally! xx

I always thought that the life of a circus performer must have a fair bit of risk, Leslie. This article has confirmed that but it is true that you have to stretch yourself to learn and progress in every walk of life.

Yes, life’s a balance between being overstretched and understretched, too much of a good thing and too little on your plate.