JULIA LEE BARCLAY-MORTON – YOGA, WATER AND REWRITING AUTISM

I interviewed writer Julia Lee Barclay-Morton about her experience of autism. Julia began as an experimental dramatist in New York, moving to the UK to

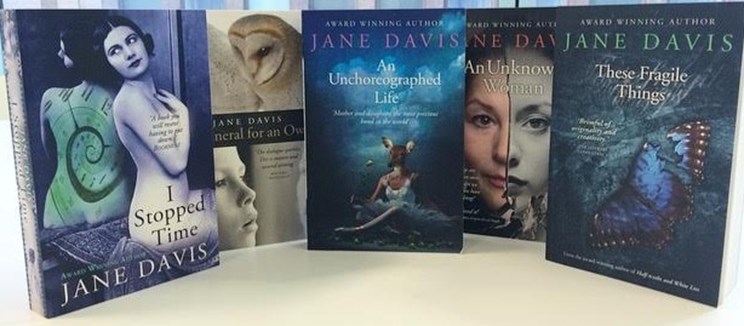

I interviewed Jane Davis, winner of the Daily Mail First Novel Award 2008 and described by The Bookseller as ‘One to Watch’. Reviewing Jane’s earlier novels, Compulsion Reads wrote about her: ‘Davis is a phenomenal writer, whose ability to create well-rounded characters that are easy to relate to feels effortless’.

Jane says about herself: “I spent my twenties and the first part of my thirties chasing promotions at work, but when I achieved what I’d set out to do, I discovered that it wasn’t what I wanted after all. It was then that I turned to writing.”

Jane Davis lives in Carshalton, Surrey with her Formula 1 obsessed, star-gazing, beer-brewing partner, surrounded by growing piles of paperbacks, CDs and general chaos. When she isn’t writing, you may spot her disappearing up a mountain with a camera in hand.

In part one of her interview, I asked Jane about the kind of novels she writes, her development as an author, and how much ‘real life material’ goes into her writing.

Leslie: As the author of eight novels, can you describe the types of writing that characterise your output, please? Which is your favourite book, and why?

Jane: Henry James wrote in an 1884 magazine article that a novel is ‘a direct impression of life’. My own favourite definition of fiction is ‘made-up truth’, which is pretty close. Whatever my subject-matter, I try to make sure that the end-product is honest, credible and authentic. I like to write about big subjects and give my characters almost impossible moral dilemmas. I don’t allow my characters a shred of privacy. I know what they’re thinking, what they’re feeling, the lies they tell, their secret fears. But I only meet them at a particular point on their journeys, usually in a highly volatile or unstable situation, and then I throw them to the lions. How people behave under pressure reveals so much about them.

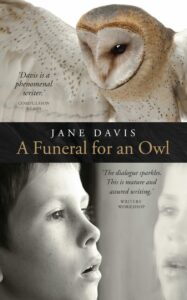

Despite the fact that it cost me my publishing deal, A Funeral for an Owl remains my favourite of all books. I bump into its characters almost daily, because it’s set within my lunchtime walk, so I have created a strata where my personal geography is overlaid with my characters’ geography. They’re very real to me.

Despite the fact that it cost me my publishing deal, A Funeral for an Owl remains my favourite of all books. I bump into its characters almost daily, because it’s set within my lunchtime walk, so I have created a strata where my personal geography is overlaid with my characters’ geography. They’re very real to me.

Leslie: What is the relationship between ‘issues’ and raw, lived experience in your books?

Jane: When challenged recently that that there were too many coincidences in my photography-themed novel, I Stopped Time, I referred the reviewer to the biography of model-turned-photographer-turned-journalist Lee Miller. I see myself as a magpie. I collect obscure facts and think, how can I recycle them? But my own truths are likely to be found in the fine detail.

What inspired me to write These Fragile Things was the discovery that a woman in Surbiton – close to where I live – claims to have seen visions of the Virgin Mary every day for the past thirty years. The Church refuses to believe her because the message she says she receives goes against their teachings. My personal feeling, for what it’s worth is, why would the Virgin Mary visit Surbiton every day if not to challenge convention? But the book also depicts issues that are part of my DNA. My grandfather’s conversion to the Catholic faith shaped my father’s childhood and impacted on my own. It was important to me that I tackled everything with great sensitivity, with each character representing a distinct point of view, and believing absolutely in that stand-point.

While I was writing Half-truths and White Lies, my middle school was pulled down to make way for a housing estate. Since it was within walking distance of my job, I made a pilgrimage every lunchtime to see the wrecking balls do their work, documenting the progress with photographs. In the evenings, writing as Peter Church, I described the dismay he felt at discovering that a block of flats had been built on the place where he used to play marbles and that more blocks had been built on the pitch where he played football. He asks himself the question, is it possible to mourn the loss of a building as you would a person? “Or is it simply that St Winifred’s was the shell that I stored so many of my memories in? How is it that my old school was torn apart and I didn’t feel a physical wrench?”

In A Funeral for an Owl, Jim discovers that his pupil Shamayal is living in the council flat that he had lived in as a boy. I knew that flat because I lived there too. The small anecdotes are things that happened to me.

I wrote An Unknown Woman in a year when my income had dropped to a level that I hadn’t earned since the late eighties, and so I chose to explore our relationship with material possessions.

I wrote An Unknown Woman in a year when my income had dropped to a level that I hadn’t earned since the late eighties, and so I chose to explore our relationship with material possessions.

It took me some time to identify that the common thread that runs through my novels is the impact of missing persons on our lives, how the hole they leave behind can be so great that it dwarfs the people we’re left with. In I Stopped Time, it was an estranged mother. I addressed the theme head-on in A Funeral for an Owl, with teenage runaways. And in These Fragile Things mother Elaine is obsessed by the child she lost to a miscarriage, almost to the exclusion of the child she has. This theme almost certainly comes from both my personal history – and that of my parents.

When I was aged seventeen, a school friend of mine was murdered. This was my first experience of a young person dying, and the ripples from that single death are still felt today. In my parents’ generation, death was far more common and was spoken about far less.

My father’s mother died when he was aged eighteen months. He and his two sisters were taken into care. As was the norm, he was separated from Marian (aged 6) and Lois (aged 4). Six months later, Marian woke to find Lois dead in the bed beside her. Lois’s death certificate says that she died of a broken heart.

My mother was a child of her father’s second marriage. His first wife had died in 1937 at the age of 37. Mum grew up knowing her two half-brothers and a half-sister. We only came into possession of a family tree last week, which shows that she had another half-brother she knew nothing about. Patrick died in 1938, just six months after his mother.

My mother also had a much loved younger sister called Alma. She and my mother were to have had a joint wedding but 10 days before the wedding date, Alma was killed in a car crash. She was just 23.

Leslie: You started writing at the age of 36. Can you describe what you were doing before that age and what led you to switch from day job to author? What were the early signs that your true vocation was to write books?

Jane: I recently completed an author survey. There was an entire section asking about early writing and story-telling experiences. What was the first story you wrote? Were you always making up stories? Did you win any writing competitions while at school? I began to think, ‘I’m not a writer. I’m a failed artist.’ You see, I made up stories as a child, but I used pictures instead of words. Right up to my O-Level year, I spent most of my spare time drawing. I’d always assumed that I would make a career in art. And then came a hard lesson. I learned that judgement of what is good art is subjective. The O-Level examiners didn’t like my work. My confidence was shaken but actually it went deeper. It dismantled my idea of who I was.

My reaction was to leave school. On the day my friends returned to sixth form college, I went to the job centre and landed my first job – in insurance. It’s an industry I remained in for the next 25 years, working my way up from claims clerk to deputy managing director. After growing up in a household with a very tight budget (five children, one salary), to earn my own money was liberating.

Although I’ve taken qualifications in my own time, I’ve never found my lack of further education to be a disadvantage. I was a manager at the age of twenty-one and a director at twenty-six, and you learn so much simply doing these things and being responsible for others. I’m not sure I would have had the confidence to write unless I had first sat in a board room and had my opinions taken seriously. But it’s true that I became frustrated by the lack of opportunity for creative output. To begin with, writing was my stress relief.

Leslie: You also say, ‘Things I wrote about come true!’ Could you expand on that statement, please?

Jane: It’s happened in less obvious ways in the past, but it happened in a huge way with my novel An Unknown Woman. The book is an exploration of how material possessions inform our identities. The action begins with my main character, Anita, standing outside the house she and her partner have lived in for fifteen years and watching it burn to the ground. It is very recognisably my house. My partner and I joked about how I might be tempting fate. But it was just a joke.

Then in February 2014, three months after I finished the first draft, my sister and her husband lost their house and practically everything they owned to the winter floods. She lived on the island on the Thames that you can see in the first photograph in this article .

I questioned if I should abandon the project. I was writing about an imagined scenario that had become a reality for someone very close to me. My sister insisted that I continue, but neither of us imagined that, over one years later, she and her husband would still be living in a rented house with what little they managed to salvage, waiting for planning permission to start rebuilding their home – and with it their lives. It was three long years and a building dispute later before they were finally back in a home of their own.

Next week, in part two of my interview with Jane Davis, I ask her about her relationship with the book industry, how and why she writes, and her more recent work.

ABOUT LESLIE TATE’S BOOKS:

I interviewed writer Julia Lee Barclay-Morton about her experience of autism. Julia began as an experimental dramatist in New York, moving to the UK to

I interviewed Gillean McDougall from Glasgow, who edited the collaborative projects Honest Error (on Charles Rennie Mackintosh and his wife Margaret Macdonald) and Writing the

I interviewed French writer Delphine de Vigan, whose book, No et moi, won the prestigious Prix des libraires. Other books of hers have won a clutch

I interviewed Joanne Limburg whose poetry collection Feminismo was shortlisted for the Forward Prize for Best First Collection; another collection, Paraphernalia, was a Poetry Book Society Recommendation. Joanne

I interviewed Katherine Magnoli about The Adventures of KatGirl, her book about a wheelchair heroine, and Katherine’s journey from low self-esteem into authorial/radio success and

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

4 responses

What an interesting interview, I love the idea of the Virgin Mary visiting Surbiton. All writers are surrounded by real life stories that must inspire or give us ideas and we should use them.

Yes, I find adapting life into a story gives it a stronger emotional charge, and makes it more authentic.

Fantastic interview, Leslie and an interesting look at the author herself.

Yes, Adele, Jane Davis is a pretty impressive author! Thank you.