JANE BURN – POETRY AS HARD GRAFT, INSPIRATION, REACTION OR EXPERIMENT?

I interviewed poet & artist Jane Burn who won the Michael Marks Environmental Poet of the Year 2023-24 with A Thousand Miles from the Sea.

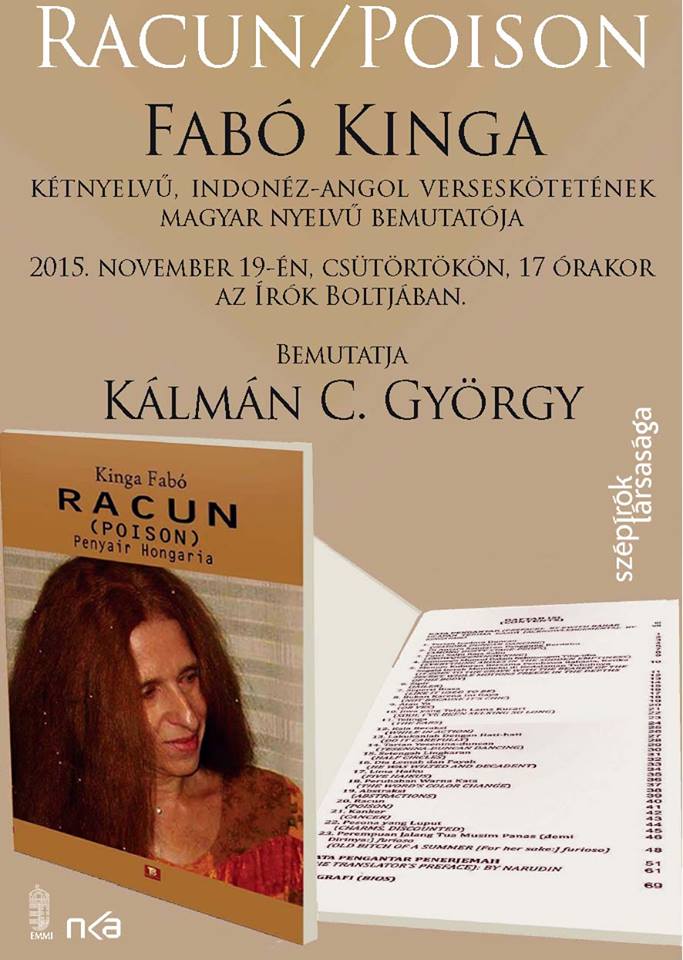

I interviewed international poet Kinga Fabó whose work has been translated into 17 different languages. Kinga has been published in journals such as Modern Poetry in Translation; Numéro Cinq, Ink Sweat & Tears, Deep Water Literary Journal and anthologies like The Significant Anthology, Women in War and World Poetry Yearbook 2015. Her latest book, a bilingual Indonesian-English poetry collection Racun/Poison was published in 2015. She lives in Budapest, Hungary.

I handle strong, unusual themes in a casual, matter-of-fact manner, in an everyday style, simply and detached – Kinga Fabó.

Leslie: I’d like to start with a poem of yours, Kinga, ’The Complaint of a Worn-out Girdle’. It’s one of two translated into English by George Szirtes, who says, ’It is actually the girdle that speaks… These poems are in effect dialogues with an invisible other, racy in diction, almost chatty but at the same time metaphysical. It is the blend of fury and wit that determine the emotional key but it is the form and rhyme that lend both the sharp, hard-edged, proverbial, almost Villonesque quality I was trying to catch.’

The Complaint of a Worn-out Girdle

How many women have I tortured? God,

how many! And how perfectly deformed

their bodies were as one by one they trod

the red carpet, swayed and posed

in gratitude to me, I who prefer a closed

door to the blatantly exposed

(and they pretend to disdain me even while

seeking my good graces, S & M style)

insist I serve them with a wide eyed smile.

Those who possess me seek the praise

– and might receive it – of the blank male gaze.

They use me and disparage me all ways

and yet are one with me, have flounced

about while in my steady grip

or slipped into me unannounced.

Talking of perverts, I am stuffed with them,

(this is where it comes to S & M),

it’s like being in a prison cell.

I am the stock where these mad bats from hell

work out. I work my magic well

and turn them out as new after a spell.

They undo me, as might anyone.

I am what they have done.

But why do they insist on carying on

with me – the feeling isn’t mutual –

with me in particular!

Why pick on me when there are

plenty – women or worms – it matters not

happy to give them all they’ve got.

All clichés, you can stuff the lot

into one old hat and call it quits.

I’m not for clichés, not one fits.

I wish they left me alone, but it’s

hopeless, I am forced to serve.

I’m always different and will swerve

from following an alien curve.

Is this their thanks? This sorry item. .

All for some man to woo or bride them.

A pity it is to prettify them.

Leslie: Can you take us through the story of how you found an original voice as a poet, please? How would you characterise your style of writing?

Kinga: My writing might be described as finding a constant vibration between the contrasting elements of ’the same and still different’ (my own term).

To explain: I always write the same poem. I always deal with the same themes in all the literary, artistic and scientific genres I use. The implication is that I have a permanent core and at the same time an altering part in all of my activities, works and artistic/mental products. However, in writing the same poem, the theme(s) might take different forms and styles. So the tone might become unusual yet strangely familiar. I handle strong, unusual themes in a casual, matter-of-fact manner, in an everyday style, simply and detached.

Your poetic voice is more or less given, I suppose. The way you write is only partly a question of choice. Of course, you always have to work on it. The relationship between instinctive vs conscious parts in a poem is constantly changing and is highly dependent on the individual poet. If you have a voice really of your own, finding and expressing it needs you to be, and remain, an outsider. It’s much more difficult to get it accepted by others than to find it for yourself.

And you must be an outsider in another sense: you must handle your poetry and yourself as an object. This attitude is very close to me. So while working my poem might become hard, cruel, wild, bizarre, brutal, full of tension, energy and intensity but still detached…

I prefer to use understatements, but using overstatements might also be a chosen style if it turns out to be conscious and reflected. In a professional poem anything goes that is decided, that is consequent; and if everything is in its right place.

Now I see I’m already in the process of describing my own style and poetic practice. As you see I love ambiguities, contrasts, asymmetries, paradoxes, accelerating tension until it becomes unbearable. I like trespassing. My poems are very quick; maybe they are pursuing somebody, maybe they are being pursued. Readers are caught at once, involved immediately in the middle of the poem. They are left with an unusual yet strangely familiar, slightly disturbing feeling, as if some kind of unnameable danger was snooping…

I suppose us poets might have an effect on our readers either by giving them the possibility of identification and recognition, or by offering surprise, astonishment, embarrassment, novelty.

Readers generally prefer to identify themselves with figures, feelings, situations that are familiar to them. The experience of ’me too, me too’ reinforces the reader’s belief that ’I’m doing well, what I do.’ — But form is more important in writing.

A poem is born together with or for the sake of its form. To take a few examples of forms:

• Rhythm, rhyme, metre.

• Shapes, enjambements, cuts, stanzas, arrangement on the page, the number of lines a stanza contains.

• 3-line stanzas (my preference).

• Structure, architecture. Title.

• Varied repetitions, repeated variations.

• Rhymes recurring unexpectedly in unusual spots.

With the last one, I call these my own ’rhymes at offence by surprise’. I often apply half-rhymes or slight-rhymes as well in poems to bring out their everyday nature. These half-poems, halfs (sic!) might be a product, a voice of my own. — Voices, noises, silence, stress, musicality.

The sound of a poem is so important for me that sometimes I give musical guides to them. These musical guides (generally in Italian) might be already pre-existing ones, e.g. ’allegro’; or made up by me, e.g. ’with restrained intensity, restrainingly’.

My punctuation is sharp and shrewd, because it’s meant to illustrate the inner music of my poems. Strictly speaking, every poem is visual and acoustic in itself: it sounds somehow and it has a visual arrangement… Sometimes I record my poem with an irregular, erratic distribution of stress…I like to think and work in total compositions. When I’ve a reading I often design my outfit so that it should suit my poems…

Leslie: Before asking some more questions I’d like to give a second example of your poetry, ‘The Promiscuous Mirror’, translated again by George Szirtes. He says: ‘Both poems are about the conventional apparatus of womanhood and presentation… ‘The Promiscuous Mirror’ is born out of the same disappointment and fury at circumstances as ‘The Girdle’, but is less gendered and will wipe out any face before it.’

The Promiscuous Mirror

1.

Is it detached or all-forgiving?

We need a passport to get through.

It nods us past in quick succession

Just anyone, no matter who.

I can rely on its detachment

As I move from place to place.

All those languages it masters,

Wherever I dare show my face!

It’s no big deal who’s looking in it

As it serves its own blind grace.

2.

It neither befriends nor breaks up with you.

Though when you’re pushed in front of it

Whether you’re plain or just plain gorgeous

It frowns and takes the brunt of it.

Could this absolute indifference

Be Absolute? (It takes no joy

In my bare flesh, nor is it bored.)

In all my phases I am simply

What seems to vanish then return,

Part of its cosmic unconcern.

3.

The distance is too terrifying.

It could be less but it is clear

Some speck of me would still appear.

The mirror will serve us blindly

And whether harshly or quite kindly

Forgets at once. There’s little fuss,

Or major choice required for us.

It lets us do just what we want.

Mine drops me quick without a trace.

Mechanically wipes out my face.

Leslie: So, can I ask, is your writing ’experimental’ or ’extreme’?

Kinga: I don’t think of myself as an experimental poet. But of course I always experiment with my raw material that is language and form alone, without being attached to this or that special poetic circle or school. Writing is a lonely activity. – Still, at the same time I’m often labelled to be an experimental, underground, alternative etc. poet. I don’t know why. Maybe it is simply because I differ so much. I don’t belong. Neither to a mentor, nor to influential groups. People don’t know what to do with me or how to handle my poetry, they cannot classify them… I myself don’t believe in classifications at all.

Leslie: Why do you take up ‘stances’ in your writing?

Kinga: I think you mean I often change the characters, the speakers, the dramatis personae as well as the locations and speech styles of my poems. I’ve some recurring characters, both fictitious and living; ones like, ’The Mistress of the Copper Mountain’ taken from Pavel Bazhov’s collected tales, or Assia Wevill, lover of Ted Hughes. My other recurring figures like ’The Little Mermaid’ or ’Snow Queen’ are from the tales of Andersen. I also have some recurring objects like mirrors or perfumes, scents. Scents are especially interesting; however they cannot be seen, their strong presence is felt. The speaker of my poem is never identical with me, the writer of it. My poems are full of players, as if in a play. Applying only one identity in one position might be boring. Be that as it may I put myself into several other identities, or put several other identities into myself.

Leslie: Who have been your main creative influences – why them?

Kinga: I’m a keen reader and I love poetry. As I’m not influenced by authorities, positions or names, I read everybody I meet. – Instead of giving a long list of my favs, I’m mentioning now Sylvia Plath. As a young poet I felt myself alone, I found myself kinless, rootless. All these feelings have remained and I’m still an outsider, but in reading Plath’ poetry I always find some reinforcement. I have to mention Emily Dickinson as well for similar reasons…I can’t tell you how eager I was to read the poets around Plath especially Hughes and Sexton. How excited I was to have been published in ’Modern Poetry in Translation’ founded by Ted Hughes. And how delighted I was to e-meet Ruth Fainlight! Plath had dedicated her poem ’Elm’ to Fainlight. ’Handbag’ is a poem by Fainlight I really admire! There are two poets – Ingrid Jonker and Alejandra Pizarnik – who can be associated with Plath I also admire for several reasons.

If I’m inspired inside, anything or anybody can be a source of inspiration. If not – nothing. When you are ’up’ anything you get in touch with will become a part of you and your writings.

Of course your creative influences are not necessarily literary ones. Negative experiences are more inspiring and influential than positive ones. People might be shocked by how often a poem comes from the dark side; from dirty, vicious, angry, hateful, killing, awkward sources. My poems have nothing to do with demure, genteel, sublime things either. Emotions are very difficult to handle in writing. Kundera wrote that the time of suffering-contests was over. Of course here and elsewhere I’m talking for myself, never normatively or generally.

’Swimming in the Rain’ is a poem by Chana Block that I must mention here. She is a master at blending philosophy with everyday life, speech and situations…

Leslie: Can you describe the expressive qualities that come naturally because you’re writing in Hungarian?

Kinga: The language and the culture you are born into influences your way of association, your creativity. Hungarian language is so isolated here in Eastern Europe and classical Hungarian literature is so rich in great poets. These facts are parts of your identity. Still identities can be changed or chosen. If you write in English or say, under a pseudonym, you automatically apply another identity so your writing will be different.

Language (langue) as an abstract structure of signs is decisive for your thinking, but speech (parole) might be more interesting for a poet. S/he might riot in sounds, syllables, words, vowel harmony. So English words are short and hard, and its sentences also crash hard. If you read a poem in a foreign language it seems to be so magical, because several parts of it always remain unsolved, undeciphered, cryptic, enigmatic…

Leslie: What are your thoughts about what is successfully communicated across languages and what is ‘lost in translation’?

Kinga: I don’t translate. Translating and writing poetry are rather different activities. Still, I’m often asked about translation maybe because I’ve been translated into several languages included such ’exotic’ ones like Indonesian, Gallego or Tamil among others. Tamil is spoken in India and is one of the most ancient languages of the world. So I was really surprised to find one of my poems in Tamil on Facebook! It happened not by design but by accident.

People have found my poems here and there on the Net, liked and translated them at random. In this respect I did nothing for being translated. – There is one exception. I’m in a constant and urgent need of a good English translator. I have not been translated into English for years. Translators find my poems too difficult. George Szirtes is the only person who is able to give back my poems in English in their fullness. Nothing is lost in his translations.

Generally, translation is a heroic and impossible venture. It’s necessary and unsolvable. However, almost all depends on the personality of the translator.

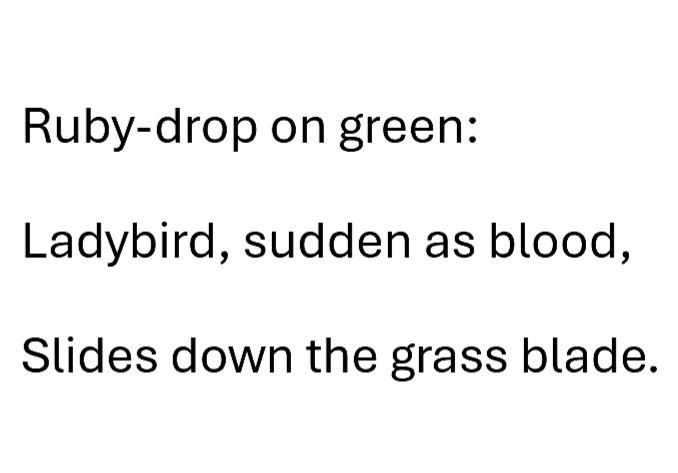

Leslie: Thank you, Kinga for a fascinating interview. I’d like to end with a haiku series of yours, in translation of course, with the Tamil underneath and the English above.

Five Haikus

Ripens sweet fragrance,

makes its fruits grow and gain weight –

as the Moon’s mask grows.

கனிந்த இனிய நறுமணம்

கனியை இன்னும் பெரிதாக்குகிறது

வளரும் நிலவின் ஒளிவட்டமாய் …

●

I’m forced on the shore

by brackets of holidays:

the world in-between.

விடுமுறைகளின் அடைப்புக்குறிகள் விரட்ட

கரை சேர்ந்து நிற்கிறேன்;

இடைப்பட்ட உலகம்.

●

Moon’s rising upwards,

I can’t follow it that high:

drags its solitude.

உதித்தெழும் நிலவை

பின்தொடர இயலவில்லை

அதன் தனிமையைப் பற்றிக்கொள்கிறேன்.

●

Neither swaggering,

nor in all submissiveness,

though it’s uncommon.

இயல்புக்கு மாறாய்

வீராப்புமில்லை

வீணாகப் பணியவுமில்லை.

●

It’s throwing fake pearls

– just a fountain not a spring –

tears being stamped out.

கண்ணீர்த்துளிகளின் வெளியேற்றமாய்

போலி முத்துக்கள் வீசியெறியப்படுகின்றன

செயற்கை நீரூற்றுதான் இயற்கையானதல்ல

Kinga Fabó’ s poem

translation: swaroob manikandan, Via : bashointernationalhaikuforum

Next week, in THE JOYS OF SYNAESTHESIA, I interview historian, musician, blogger and author, Eilis Phillips, about her synaesthesia.

ABOUT LESLIE TATE’S BOOKS:

I interviewed poet & artist Jane Burn who won the Michael Marks Environmental Poet of the Year 2023-24 with A Thousand Miles from the Sea.

I interviewed ex-broadcaster and poet Polly Oliver about oral and visual poetry, her compositional methods, and learning the Welsh language. Polly says, “I absolutely love

I interviewed Jo Howell who says about herself: “I’ve been a professional photographic artist since I left Uni in 2009. I am a cyanotype specialist.

Poet Tracey Rhys, writer of Teaching a Bird to Sing and winner of the Poetry Archive’s video competition reviews Ways To Be Equally Human. Tracey,

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

7 responses

Thank you for this introduction to Kinga, Leslie. Her poems are quite extraordinary and I loved the haikus too.

Thanks, Robbie. The merit goes to Leslie…I just posted a poem of mine, ‘Mirror Image’ translated by George Szirtes, published in Modern Poetry in Translation…

🙂 🙂 🙂

Thanks, Robbie. Yes, I agree, she’s very individual and strong in her phrasing. 🙂 🙂 🙂

Wonderful to read, thanks for the interview.

I’m always glad if people discover new writers – or discover more about writers they’ve already read – through this blog!

Great.