Part 2 MARK STATMAN: MEXICO AND THE POETRY OF GRIEF AND CELEBRATION

Part 2 of my interview with Mark Statman looks closely at Mark’s Latin American poetic influences, his life in Mexico and ends with an extract

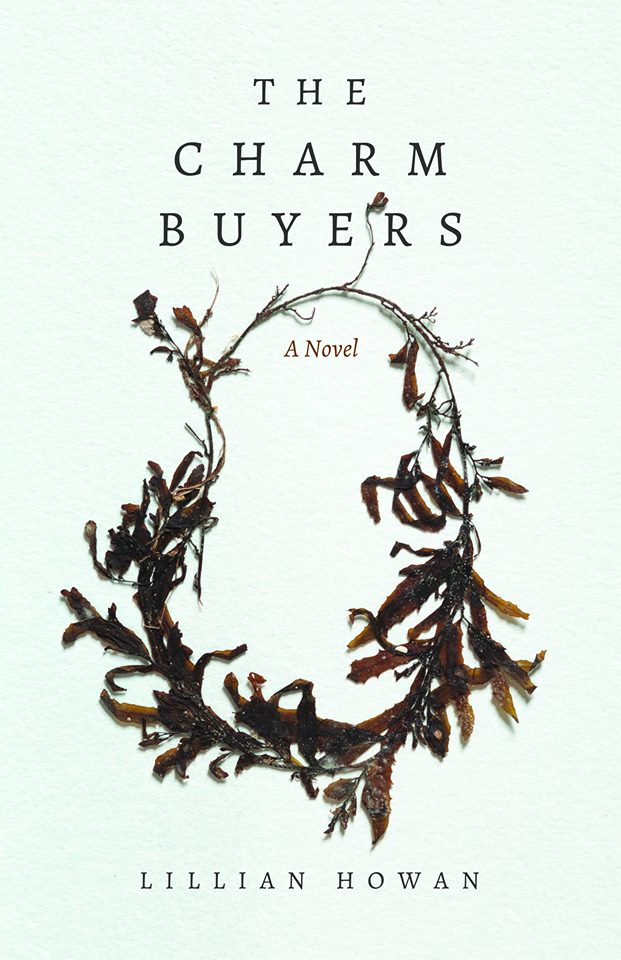

In this two-part feature, Lillian Howan, author of a powerful novel set in Tahiti, offers a revealing interview and a lyrical essay describing her cultural heritage, her creativity and her experience of lupus. It also includes pictures of Polynesian Islands threatened by climate change, taken by Lillian’s sister-in-law, Françoise Holozet-Howan.

PICTURES OF POLYNESIA

This is a message from Françoise Holozet-Howan, about these photographs of Polynesia:

“Paradise is everywhere in these photos. But soon what you see here will be underwater. I’m happy to share these photos of the Tuamotu, Gambier, and Austral islands, so that people will know these places are real. Those who live here are beginning to leave their homes, their land, because everything will be flooded due to climate change. I’ve had people show me places saying ‘yes, my home was here’ or ‘when I was a child, we lived here’ and the places they show me are just ocean now. Everything has been covered by water.

We need international aid – not money, but ideas. We need people to think about ideas that can help us, that can stop us from losing our homes and the only land we have known. We have always made our living from the land and the water, but we’re reaching the point where we can no longer feed ourselves due to climate change.

I’m hoping that when you look at these photos, you think ‘woah!’ It’s beautiful. It’s paradise. But it’s being lost. On this planet, we cannot continue like this. We hope that, internationally, people will realize that we are here. This is why I would like to share these beautiful photos: to show that paradise is real, but it’s being lost underwater. We know that climate change is real because we see the ocean covering land that was once there. What’s being lost…? This is our home.”

INTERVIEW WITH LILLIAN HOWAN

Lillian Howan‘s writings have appeared in the Asian American Literary Review, Café Irreal, Calyx, New England Review, Vice Versa, and the anthologies Ms Aligned 2 & Under Western Eyes.

In Part One I interviewed her about her early years, her writing, and her autoimmune condition.

Leslie: Can you tell us about your upbringing, please?

Lillian: I was traveling even before I was born. My parents moved from Paris to California two months before my birth. My parents were both Hakka, known as ‘The Guest People’ of China, a historically semi-nomadic group.

When I was two, my parents returned with me to Tahiti where my father was born and where both my parents had spent a substantial part of their childhood. My mother was born in Raiatea, the ancient spiritual center of Polynesia, and had moved to Tahiti when she was eleven. One of my earliest memories is riding my tricycle as fast as I could around my great-grandparents’ garden of dark trees and red earth. My great-grandfather sat in a chair by the front entrance, and my mother later told me that he was amused by my tricycle driving. I do remember feeling that I should figure out a way to go faster on that tricycle.

My first language was French because my parents had met in France. At the time, in the late 1940s and early 1950s, there were no colleges or universities in Tahiti, so my parents had to travel to France to complete their higher education. My mother who attended the University of Paris was one of the first women from Tahiti to receive a college education.

My second language was Hakka. I speak a rather antiquated version of Hakka, enforced by my maternal grandfather who was strict about using proper Hakka words that weren’t a mixture of French or English. For example, I was taught to call the color orange: kim um vong or goldfish yellow, whereas most younger family members follow French custom and use the same word for the color and the fruit. My mother said that when I was a toddler in Tahiti, I talked to the dogs and cats of Hakka families in Hakka, and the dogs and cats of French families in French.

My third language was English. I learned this in elementary school since I returned with my parents from Tahiti to California where I started kindergarten.

Leslie: What is the story of you becoming an author?

Lillian: I first started writing when I was eight. I picked up a red pencil one day after school and sat down and wrote. One of my first stories was about a hamburger named Jane.

Several years later, I began thinking that I had to get a ‘real job’, and I went to the University of California, Berkeley, Law School and became a lawyer. After I had been working for two years, one evening I found myself starting to write a story at my desk. It was similar to when I was eight, only at twenty-six, I picked up a pen, instead of a red pencil, to start writing. The story was called ‘Sixty Seconds in the Life of a Bar Examinee’. I had taken the California Bar Exam in a vast, cavernous, underground hall and for the first few minutes of the exam, I had been absolutely panic-stricken. In the story, I imagined images of my life passing before my eyes when, in reality, all I had actually thought about was that I was going to throw up right then and there. That was the beginning of my writing as an adult because I’ve never stopped writing from that time.

I didn’t think seriously about publishing my writing for decades, although a few of my short stories and essays were published in literary journals. When I was forty-nine, my youngest son Tien became critically ill with lupus at the age of nine. His kidneys failed and he was placed on dialysis. While he was awaiting a kidney transplant, I spent many weeks with him in the hospital during various health crises. Synchronistically, before my son became ill, I had begun writing a manuscript about a young woman with a serious autoimmune disease in Tahiti – and it was during Tien’s long hospitalizations that the idea of this novel truly developed. When Tien began returning to school, he had to take many medications twice daily, plus he had a central line – a catheter for pediatric dialysis. My friend Laura Pollard Gorjance was working at his school and generously shared her office with me so that I could give Tien his meds. Her office was where I wrote the first complete draft of The Charm Buyers. It took me seven years to write this novel.

I had worked with the University of Hawai’i Press as the editor of a collection of short stories by the remarkable, legendary playwright and author Wakako Yamauchi. The University of Hawai’i Press acquisitions editor whom I had worked with, Masako Ikeda, expressed interest in The Charm Buyers. Tien was still experiencing health challenges, and I was beginning to exhibit symptoms of lupus myself, although I would not be officially diagnosed until later. It had become important for me to try to publish The Charm Buyers, a novel about Tahiti and the islands where my parents were born and about the underlying themes of nuclear testing, illness, love, loss, magic, and renewal. I was fifty- eight years old when University of Hawai’i Press published my first novel, The Charm Buyers.

Leslie: How have personal health issues changed your understanding of life?

Lillian: Illness is a limitation. That has been my first, overwhelming perception of my own autoimmune illness. When I look back at my life before, it seems as if my energy was so abundant, whereas now I’m constantly deciding how to live each day based on limited strength and energy. I’m continually feeling both a sense of profound loss and a sense of renewed appreciation for the basics of existence. Illness has forced me to discover a more fundamental sense of what it means to be alive.

I’m reminded of a remarkable interview you posted with Romany poet Raine Geoghegan, author of Apple Water: Povel Panni, where she observed that “as a society we do not pay enough attention to being in the present moment, to take time out for relaxation or healing.” As someone with fibromyalgia and M.E., she talked about a moment where she asked herself what she could do, and her response was that “you can breathe, pray, write.” These insights revealed to me that illness can emphasize – however painfully – the most essential aspects of life, basics often overlooked in the flush of health.

‘The Spoon Theory’ by Christine Miserando, a writer who lives with lupus, vividly expresses what it feels like to live with the limitations imposed by chronic illness. Miserando used spoons while sitting in a café with a friend who wished to understand more about chronic illness. Each spoon represented a limited allotment of energy and the number of spoons represented the total amount of energy for that day. As her friend went through a description of a normal day, Miserando then proceeded to take a spoon away, one by one, representing the amount of energy being spent. When her friend realized that she had only few spoons left and that her choices were severely limited before the day had even begun to end, her eyes filled with tears realizing that Miserando had to live like this every day.

The body continually puts forth efforts at healing, even if this renewal is counterbalanced by disease. Living with lupus, with flares when my skin erupts in rashes and lesions, when everything from my hair to my digestion to my breathing feels impaired, also opens the door for the bodily effort at healing. I’ve found it remarkable how the body struggles immensely to repair itself. Sometimes when I’ve felt the most wretched, this healing force has made itself known as something both within and as something outside of myself.

Lupus is cyclical, with times of affliction and times of renewed health. As a writer, I experience times of healing as times of inspiration. Physical healing appears together with creative expression. Because my breathing can be difficult when I’m ill, it’s a wondrous relief when regular breathing returns, when I no longer have to think about each breath. Often as a writer, it seems as if publishing and external recognition are the marks of creativity – but my chronic illness has taught me that creativity flows more deeply and in more basic, essential ways. Just breathing, the inward and outward flow, in and out of the body feels utterly miraculous when a lupus crisis finally ends and I’m breathing regularly again. The essence of creativity exists in the renewal of each breath. Poems and stories embody creative expression, but the source of healing creative connection exists in the most simple acts, in the air that flows in and out of our bodies.

Next week Lillian Howan writes a lyrical essay about growing up in Tahiti and losing her father.

ABOUT LESLIE TATE’S BOOKS:

Part 2 of my interview with Mark Statman looks closely at Mark’s Latin American poetic influences, his life in Mexico and ends with an extract

I interviewed international poet and translator Mark Statman about Volverse/Volver, his 14th published collection. Mark, who has won national arts awards, is Emeritus Professor of Literary

I interviewed Lisa Dart, finalist in the Grolier, Aesthetica and Troubadour Poetry Prizes and author of The Linguistics of Light (poems, Salt, 2008), Fathom (prose

I interviewed writer Julia Lee Barclay-Morton about her experience of autism. Julia began as an experimental dramatist in New York, moving to the UK to

I interviewed Gillean McDougall from Glasgow, who edited the collaborative projects Honest Error (on Charles Rennie Mackintosh and his wife Margaret Macdonald) and Writing the

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

8 responses

Wonderful! Thanks to Lillian for sharing and to you Leslie for enabling, Chrys

✍?❤☀✍

A truly inspiring interview and the novel sounds fantastic also. Thanks, Leslie and Lillian and I look back to part 2.

Thanks Olga. Part 2 next Monday is my favourite piece of writing published on this blog!

A wonderful first part of the interview and I look forward to part two. So many interesting elements from the tragic loss of parts of the world that are truly paradise to the struggle to maintain creativity when faced with a chronic illness. Thank you both Leslie and Lillian.. Will put in the blogger daily this evening.. hugs

Thank you, Sally! ❤❤❤

Thank you for a fascinating interview.

The limitations imposed by a chronic illness can be liberating.

I try to maximize my productivity to compensate for the illness; at times, I’m more productive

than I’ve ever been.

These words had resonance: “Illness has forced me to discover a more fundamental sense of what it means to be alive.”

For the longest time I felt like a ‘nothing’ because I had no ‘role’ to play at work.

I had to find a more personal and moral reason for being alive.

Thank you for a thought provoking interview

Thanks for your story, Rob, and how you cope with chronic illness.