Part 2 MARK STATMAN: MEXICO AND THE POETRY OF GRIEF AND CELEBRATION

Part 2 of my interview with Mark Statman looks closely at Mark’s Latin American poetic influences, his life in Mexico and ends with an extract

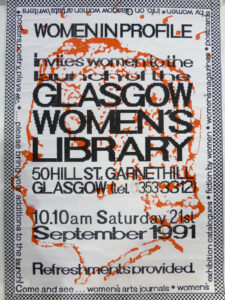

I interviewed feminist researcher Rachel Thain-Gray about Glasgow Women’s Library, a collection of iconic publications and objects testifying to the importance of women in history. Glasgow Women’s Library has won no less than seven awards. It began from events run by feminist artists and activists during Glasgow’s year as the European City of Culture in 1990.

Rachel Thain-Grey, whose doctorate examines feminist museums across the world, describes how GWL continues to put on exhibitions and events that showcase the full range of women’s history while informing the struggle for gender equality today.

Leslie: In a nutshell, what does the Glasgow Women’s Library display, how does it display it, and what’s your role there?

Rachel: GWL is a very special museum as it blurs the boundaries of museum, archive and library; so regularly our exhibitions display related objects, archive items and books telling the story of women’s lives, activism and ideas. My role has been varied in the organisation, beginning in 2013 when I delivered the Mixing the Colours project addressing the lack of women’s voices in action against sectarianism in Scotland.

Since then I have delivered prejudice reduction work examining hate crime against women and delivering our Equality in Progress project. My most recent project was Decoding Inequality, which used the collections at GWL to produce an exhibition about women’s inequality and activism across race, disability, sexuality, class and gender identity.

Leslie: How did you first become a researcher and curator? What drew you to these jobs and why do you think you’re suited to them?

Rachel: I’ve only recently started to call myself a researcher and very tentatively, a curator! I began my career in a grassroots arts organisation while completing my undergraduate in Applied Arts. My dissertation explored the Labour government’s promotion of a social inclusion agenda using the arts at the time (the 1990s) and the history of art for social good since the 1960s. After graduation, I wanted to focus my work on addressing violence against women and went on to train statutory organisations in the complexities of domestic abuse. This helped me to understand how women’s inequality directly sustains toxic masculinity in intimate relationships.

My return to the arts at GWL has been a really valuable ‘gathering’ of knowledge and experience with a focus on gender, justice and fairness – my passions!

Leslie: Can you describe, please, how you work for social justice via museums?

Rachel: I am currently exploring the concept of social justice in museums (specifically feminist museums) as part of my PhD. What is becoming clear for me is the difference between the concepts of ‘inclusion’ and ‘social justice’. I think that ‘inclusion’ can bolster systems of difference between people. This is largely based on how much access people have to power in museums. Social justice, for me, is about ensuring our organisations have transparent ease of access for all people to the museum’s resources across leadership, infrastructure, physical space, funding, programming, as audiences and digital spaces.

Leslie: How do you research women’s history when records are scarce?

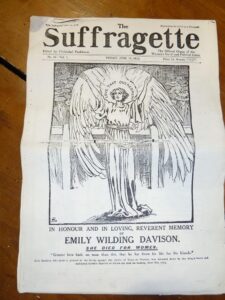

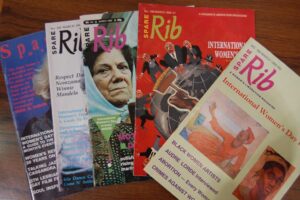

Rachel: I know that so much of women’s historical records have been deemed unimportant and without value but women have collected their own history for hundreds of years. It is there if you know where to look. GWL (like other women’s museums) is a repository where women have donated the objects and items that document their achievements, positioning them as leaders in our societies.

Leslie: Would you like to give (and evaluate?) a few examples, please, of how this quote from Decoding Inequality has been translated into action: “This is democratization in action: deciding which objects are worthy of exhibition. The nature of cultural ownership…is itself a major theme.”

Rachel: The objects on display were selected by a team of staff and volunteers. There was no ‘one’ authority in choosing the objects. Our sole intention as a team was to source items that reflected the nature of inequality, and how it is experienced by the full range of women. So, the goal was a developing narrative, rather than the demonstration of ‘established knowledge’ by one curator. The women working across the group were representational across class, race, (dis)ability and sexuality ensuring the presence of different perspectives and interpretations of materials.

Leslie: What’s the story behind museums in Glasgow such as the Kelvingrove and the Hunterian beginning to redress the diversity imbalance (and how successful have they been)?

Rachel: My focus at the moment is on women’s museums, recording what they do in order to understand the complexities of intersectional feminist practice in action. Historically feminists have worked in large institutions, undertaking important exhibitions and collaboratory work aimed at structural change. This has rarely been successful. The labour of this process is well documented, and in the 1980s resulted in many women breaking away to establish their own collectives and women’s museums.

I welcome the changes that many mainstream institutions want to make at the moment in terms of equalities; there are forty years of theoretical and practical writing on this subject. I hope they manage to sustain and embed what they’re doing.

Leslie: How do you try to make women’s herstories alive, vibrant, exciting, detailed and engaging?

Rachel: One of my approaches is to simply ask ‘how does this object/item relate to contemporary issues?’ This allows us to chart advances or setbacks in women’s ongoing fight for equality, to demonstrate their strategies and, what I believe to be really interesting, to document the methods used to keep women unequal. Only by revealing and understanding these techniques of power can we continue to deconstruct and fight against them into the future.

Next week I interview Tania Clarke therapeutic coach, psychotherapist and hypnotherapist, about her methods and how her childhood shaped her.

A

ABOUT LESLIE TATE’S BOOKS:

Part 2 of my interview with Mark Statman looks closely at Mark’s Latin American poetic influences, his life in Mexico and ends with an extract

I interviewed international poet and translator Mark Statman about Volverse/Volver, his 14th published collection. Mark, who has won national arts awards, is Emeritus Professor of Literary

I interviewed Lisa Dart, finalist in the Grolier, Aesthetica and Troubadour Poetry Prizes and author of The Linguistics of Light (poems, Salt, 2008), Fathom (prose

I interviewed writer Julia Lee Barclay-Morton about her experience of autism. Julia began as an experimental dramatist in New York, moving to the UK to

I interviewed Gillean McDougall from Glasgow, who edited the collaborative projects Honest Error (on Charles Rennie Mackintosh and his wife Margaret Macdonald) and Writing the

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

2 responses

This is fascinating. I have also noticed that there is limited recorded history about women. I read a most interesting article yesterday about Louise May Alcott (author of Little Women) and what an activist for women’s rights she was. I had no idea.

Thanks, Robbie Cheadle! As I commented on Facebook:

The women of Glasgow have had a much bigger influence than people realise. For instance Margaret MacDonald, wife of Charles Rennie Mackintosh. You can find out about her in the Kelvingrove Museum, which deserves a couple of days! Glasgow is a fascinating place, full of culture – rather distant for you I’m afraid, but for anyone reading this in the UK I recommended a visit – and the Women’s Library is a must. We booked our train from London months in advance to avoid the greenhouse gasses caused by planes. It was cheap that way and much more interesting than sitting waiting at airports,