SELF-HELP AND RESILIENCE IN THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO

I interviewed Bertin Kalimbiro from the Democratic Republic of Congo about his work in the Goma region to grow food safely and help people threatened

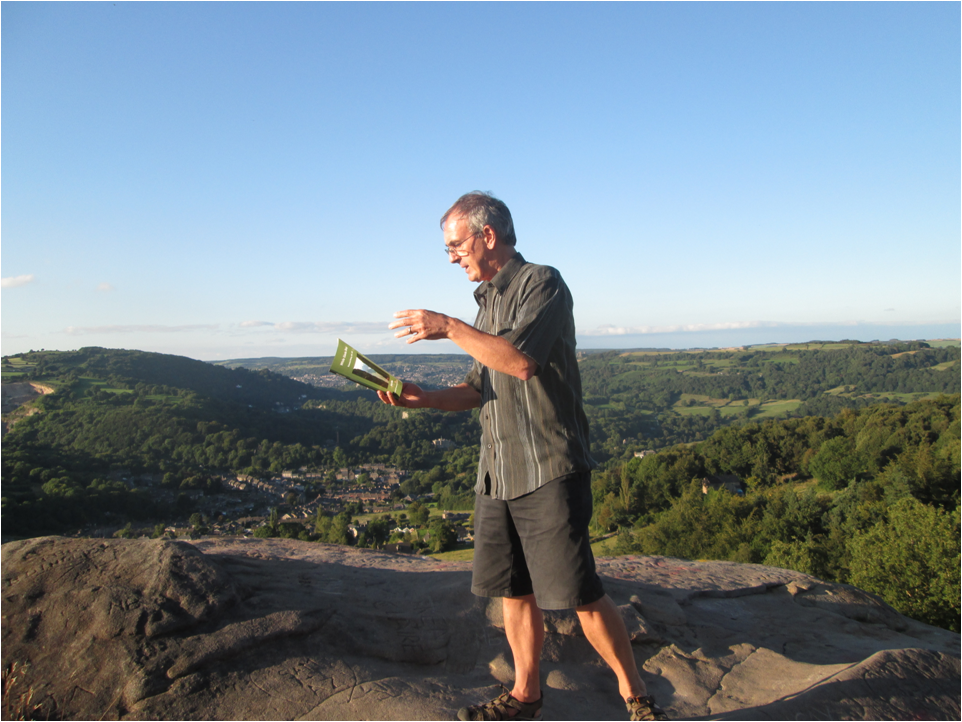

In part two of my interview with Andy Miller, winner of the 2011 Yeovil Poetry Prize, I asked about his second and third books, both written in mixed styles. Andy tells the story of putting together ‘lyrical essays’ in one book and ‘edited diaries’ in another.

Leslie: What were the deeper intentions of writing about music and travel in ‘While Giants Sleep’? How does the book deal with life stages and the psychology of relationships?

Andy: My immediate response is to say that I did not really have deeper intentions and that the book is a collection of miscellaneous pieces without any strong unifying themes. But that is not completely correct.

I began writing for publication professionally when I was training as an educational psychologist at the University of Sheffield in the mid-1970s. I had a fieldwork supervisor at that time who cajoled me into writing a paper jointly with him for journal submission. I had little opportunity to decline the ‘invitation’ (I needed to pass the course!) and I was thrilled to be inducted into the world of publication whilst being equally terrified of being exposed as a lightweight and imposter with ideas way above his station.

The paper was accepted. And the sky did not fall in. In fact, to this day, I do not know whether anybody in the world has ever read it. But this was the beginning of a very satisfying and career-long practice of submitting research, case studies and opinion pieces to, and frequently being accepted by, journals and book publishers.

I was also, albeit far less frequently, continuing an older pattern of writing outside my professional role. My first ‘published’ piece, in my mid-teens, had been a poem in my school magazine followed in subsequent years by similar contributions to college publications. This practice died away with a busy work schedule and a young family until, in the mid-1980s, I found myself going through a very painful separation and divorce and felt compelled to write about my feelings and experiences, mainly in a sequence of poems. Living by this time on the edge of the Peak District, I was also able to reconnect with rock climbing, an activity begun in my late teens on the Dorset sea cliffs. The close bonds formed from holding a rope – in essence holding a friend’s life – in one’s hands, the intense concentration required to the temporary exclusion of any other thoughts and feelings, the physical exertion and the huge presence of Nature, all helped sustain me through this difficult period. And gave me plenty to write about!

I became more confident about submitting for publication and was fortunate to have poems accepted by Iota, Staple, Envoi and Orbis, as well as Commended and Highly Commended in several national competitions. When I started climbing in the 1960s, the books and articles on the subject were almost all of a functional or procedural nature. With a few exceptions, not much of what was published aspired to be ‘literary’, in the sense in which we now use the term, but this was what I wanted to write. (Over the last twenty-five years or so, of course, there has been a considerable growth, led by superb writers such as Robert McFarlane and Kathleen Jamie).

I knew that attempting to write about either subject – climbing or relationships – was to enter a potential mine field as both can so easily encourage self-indulgence and purple prose. But, in the late 1980s, I did self-publish a small collection of prose and poetry that attempted to meld the two areas together. It was called ‘Hanging in the Balance’ and did it well, critically if not commercially. ‘She’ magazine published one of the pieces, others featured in climbing magazines and journals.

And there this aspect of my writing rested for a couple of decades until I retired from full-time work in 2008. With more time on my hands, I then settled to revise work written but never finished decades earlier. To my surprise and delight, one of these pieces won the Yeovil Poetry Prize in 2011 and this was closely followed by a request from the British Mountaineering Council for permission to use extracts from two of my essays in a forthcoming publication.

With renewed confidence in this work, and because much of it existed only on fading and disintegrating sheets of paper, I decided that I needed more durable copies. Typing everything into a computer and then learning about developments in easily accessible, self-publishing software, led to the idea of binding these pieces together for just myself into book form. The final steps on this journey, inevitably really given the self-publicist who regularly commandeers my being, were wondering whether there might be a wider interest in such a book and speculating on what could be said to link its varied contents. Mountaineering? Yes. Travel to and among these mountains? Obviously. Separation, divorce, new phases of life and their psychological aspects? Check.

So, I suppose the unifying theme of ‘While Giants Sleep’ is a journey through ‘mid-life’ with, in my case, diversions into climbing and, given my profession, reflections on the psychological aspects of relationships during this phase of life.

Leslie: What are your thoughts about the possible audience, purpose and psychology of writing a diary, as in your book ‘The Ragged Weave of Yesterday’?

Andy: ‘The Ragged Weave of Yesterday’ is the last of the trio of self-published books that I have produced in recent years and your question goes right to the nub of the book.

I began writing a daily diary when I was twenty in 1967 and have continued, on and off, ever since. When its half century came up in 2017, I estimated that I had written more than 1.6 million words (more than three times the length of ‘War and Peace’!) and made entries for over 9,000 days.

It was news from Colorado in 2012, news from the wife of one of my oldest and closest friends, that sent me searching through my scribbled volumes and which, in turn, confronted me with your exact questions. My friend, also called Andy, had received a serious diagnosis and Lyn, his wife, had asked that I send emails, photos or whatever to help cheer and sustain him. As we had first met sleeping in the same cold and draughty barn in Snowdonia over Easter 1967 and subsequently shared many climbing adventures, I decided to trawl my diaries and send him selected snippets from our finest, funniest and most fear-inducing moments.

Although I found our first meeting easily enough, as I searched further I ran into a host of problems. Distractions were everywhere and diverted me from my task for considerable lengths of time. Events were also often not located in the months or years I had remembered. I had no recourse to electronic search mechanisms, of course, and the thousands of hand-written pages had to be leafed through manually. One strange and unanticipated consequence was the oppressive and depressing effect that all this searching produced. Instead of bringing back years when we were all young, adventurous and carrying few of the responsibilities that would come later, I felt weighed down by the sheer amount of random detail (and my self-absorption). Had I used my time to best effect, made the most of opportunities?

Andy and Lyn replied that they enjoyed the extracts I had sent but I was, by then, contemplating junking the lot, putting all the sagging, splitting, dust-gathering volumes to the fire and being free of them. I knew this would be a drastic and irreversible act but steeled myself to do it. And then, as I was just about committed to their destruction, an obvious solution became apparent.

Editing! Once this idea came my mood lifted. I would edit this bulk down to a more manageable size. Then, with the chosen selection digitally stored, I could, if I wished, destroy all those physical manifestations scowling at me daily from my shelves.

Once I began to entertain the idea of editing, one dilemma after another sprang to mind. Do I extract the same number of pieces from each year? Say, three or five or whatever, to give a flavour of that year? And what does ‘flavour’ mean? If one year contains far more ‘big’ events – either personal in terms of births, deaths, marriages, career, holidays, or world-shattering political and cultural phenomena – then shouldn’t that year merit more extracts than a humdrum, keeping-one’s-head-down and cracking-on sort of year?

Perhaps organising my material as a sequence of chapters might prove more workable? There could be one on family, possibly, another on career. I might include one on politics or news items more generally, especially my observations and reflections on events as they unfolded. Hobbies, especially climbing and walking, would probably have their own, fairly major section but so too would friends and, especially more latterly, the books I had read. How would I begin to tackle the ups and downs of my love life? Should I, in fact, even attempt to do so?

As I mused on various formats, the sheer presence of this huge amount of words again began to weigh on me. If I wasn’t careful my various editing schemes would result in a rearranged body of prose almost as long as the original. But there were other, more pressing issues. I first needed to address, before the sense of oppression would lift and I could attempt any method of précis, the authorial voice of my adolescent self and the discomfort and embarrassment it generated, and my shifting and sometimes vague purposes for initiating and then sustaining the whole enterprise for so long. My sense of the audience for it all also seemed elusive, swimming into focus on occasions before fading and eventually being replaced.

A little earlier, I had read and thoroughly enjoyed Geoff Dyer’s ‘Out of Sheer Rage’ in which the author sets out to write a biography of DH Lawrence. The book is a very humorous tale of procrastination and indecision, including dragging his long-suffering girlfriend to also live in the various countries that Lawrence made his home, all in a search for inspiration. Along the way, Dyer tells of his attempts to get inside the mind of his subject and expose the essence of his art. What I enjoyed so much about the book was not just Dyer’s witty and self-deprecating portrayal of his continuing failure in his mission but the fact that, in this way, he ends up actually writing a quite brilliant, if unorthodox, study of Lawrence.

When I came to write about my struggles with my diaries, I think Dyer’s book exerted an unrecognised influence on me. ‘The Ragged Weave of Yesterday’ becomes, in the end, a detailed exploration of all the questions and dilemmas raised above and, in doing so, serves as an attempt to edit my diaries, particularly over the period 1967 – 1975.

To edit my diaries, I eventually realised, from the huge jumble of memories, incidents and stories, was to edit my life.

Next week, I interview magician Paul Regan.

ABOUT LESLIE TATE’S BOOKS:

I interviewed Bertin Kalimbiro from the Democratic Republic of Congo about his work in the Goma region to grow food safely and help people threatened

I interviewed computer expert and sustainability campaigner Dr Erlijn van Genuchten, who writes easy-to-understand books based on science full of practical suggestions for planet-friendly living.

I interviewed Canadian cartoonist Dawn Mockler about how she works on cartoons that might be environmental or wordless but always witty – especially her famous

I inteviewed Helen M Stevens about how she has revived the art of embroidery, creating original contemporary patterns while studying and drawing on, “One of

I interviewed Councillor Rachel Smith-Lyte about the origins of her passion for nature and her environmental activism. Rachel tells the story of her teaching (and

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

2 responses

Great! Thanks for this, Leslie

It a good second half. Thank you! 🙂