Part 2 MARK STATMAN: MEXICO AND THE POETRY OF GRIEF AND CELEBRATION

Part 2 of my interview with Mark Statman looks closely at Mark’s Latin American poetic influences, his life in Mexico and ends with an extract

I interviewed Chisato Minamimura, a Deaf dance artist who has performed in over 40 international locations working with Candoco Dance Company, Graeae Theatre Company and others. She appeared at the London Paralympic Opening Ceremony 2012 and Rio 2016 Paralympic Cultural Olympiad. Chisato, by collaborating with cutting-edge digital artists, has created a unique style of choreography from a Deaf perspective that she calls ‘visual sound/ music’.

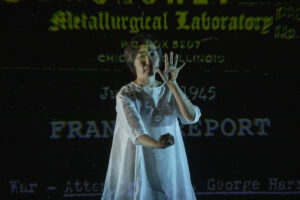

Chisato’s most recent touring work ‘Scored in Silence’ is a digital artwork that unpacks the hidden perspectives of Deaf Hibakusha, survivors of the atom bombs that fell in Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945, reliving their experiences at the time and thereafter.

This interview was conducted with the help of Peter Abraham, BSL Interpreter, and Producer, Amy Zamarippa Solis.

Leslie: I believe you’ve had an unusual education. Can you tell us about it, please?

Chisato: My education began in Japan, where I was moved to a hearing school by my parents. At the time Deaf schools did not allow sign language and insisted on lip reading, which slowed everyone to the same basic level of learning. The hearing school pushed me on, although I still had to lip read – which was, and is, difficult and exhausting. Fortunately, I had good friends who helped me and I was able to employ humour to survive. I remember, because I had to sit at the front to lip read, I got showered with spit from one teacher while he lectured. We were expected to take notes, but with this teacher I had to protect myself by holding up a see-through plastic sheet, slipped out from underneath my writing paper. I could lip-read but my hands were full, so I couldn’t take notes. Fortunately, my friends were clever and aware of my needs, so they passed over their notes to me without question. However, when it came to exams my friends didn’t look at their own notes enough. As a result, they ended in the bottom half while, because I studied the notes, I was always in the top ten! Another spur for me was that my family and the head teacher pushed me. At that time there were low expectations for Deaf children, so I wanted to prove by example how capable we can be.

Leslie: How did you learn to dance, especially as a Deaf person? What helped and what were the barriers?

Chisato: After studying art at my hearing school, learning oil painting, watercolours etc, I went up to Japanese university to specialise in the subject. Selecting Japanese art (using powdered mineral pigments instead of oils) as my strand of learning, I painted every day, but I felt I wasn’t responding to my own work. I didn’t know what to do. Then I got a letter from an arts organisation offering a dance workshop in London for disabled and non-disabled people run by Wolfgang Stange, a German living in London. When he came to Tokyo I was still uncertain about accepting the London offer. I believed that dancers had to hear and follow music, so I wondered how I could be involved. But then, I thought, why not give it a go? I was young and adventurous and it was an opportunity to branch out into 3D expression, which would be a change from the 2D art I’d been working at till then. So I accepted and at first simply ignored the music and improvised my moves.

Later I worked as a dancer for Candoco Dance Company. I discovered an unexpected barrier there because, having an invisible sensory disability in a non-disabled body, people expected me to move like a hearing dancer. The non-disabled dancers at Candoco were professionals with years of training, I’d had just a one-year course at Trinity Laban in London. The difference in skill levels was enormous – which meant that dance education itself was a big barrier for me. What happened, of course, was that I found a way to use deafness to my benefit. My so-called disability was a strength because it helped me to approach dancing in a very different way.

Leslie: Could you describe briefly, for people not familiar with what you do, the range of your work, please.

Chisato: I’m a Deaf artist and performer who is interested in communicating sensory experience. I regard being Deaf as a sensory condition, rather than a disability, and I don’t expect people to feel sympathy for me. To me, the human senses are shaped like a five-pointed star. These five points are: sight, hearing, smell, taste and touch. Even with hearing people, their sensory stars are shaped differently. For instance, with some people’s stars the hearing point is strong and the taste point is weak – meaning that the person isn’t too bothered whether food is good or bad. In my case, my sensory star has four obvious points – but the fifth point, my hearing, is there as well. It emerges through my use of digital art.

The story of the shows I’ve put on begins with my move to Britain, working with a mixed disabled and non-disabled dance company called Candoco. It’s a touring rep company with different external choreographers. Working with them I saw how the different bodies could dance together to create one magical, integrated performance. But I needed to find another way of working together. The key question I asked myself was ‘how do I fit into a dance company moving to music when I can’t hear it?’ My answer came from a famous British choreographer called Jonathan Burrows who was mentoring me at the time. Jonathan said, “Chisato why don’t you create a musical score?” At the same time, I was reading books about music by a Japanese composer, Toru Takemitsu, John Cage and others. Their books said that music is similar to Maths.

Realising that I could not see music but I could see Maths, I imagined creating a visual musical score. It would be mathematical with the dancer becoming a musical instrument, like the violin or piano for example. But then I realised that what I’d worked out wasn’t quite enough. Given my unusual sensory star shape, the missing ingredient I needed was digital art.

The next step was when Short Circuit created festival for deaf and disabled artists and digital experts to work together and I met Dave Packer, an animator. We created a film together, with the camera shooting from above on me dancing on a floor in a car park. Normally you’d just see my head, moving, but Dave copied my head digitally so there were multiple heads bobbing round. By doing this, he’d created what I call a ‘visual rhythm’, and that’s what I needed and wanted.

From there we developed the live film project ‘Soundmoves’ with portable technology. The film starts when the camera senses movement, converting gestures into sound. This is a technological development we’re still exploring, allowing us to show sound visually.

All these projects led on in one way or another to my show ‘Scored in Silence’.

Leslie: How did ‘Scored in Silence’ come about, please?

Chisato: In 2018 I went to Japan and met an old Japanese lady who told me things, using Japanese sign language. She described her experience as a Deaf person living in Hiroshima at the end of WW2. Because of lack of information as a deaf person, she didn’t know what the atom bomb was till much later. So when it dropped, she said she saw a beautiful explosion. She was lucky enough to escape, but when she got home nobody was there. Her small garden was destroyed and when she checked the chicken house, she found black, flattened bits of chicken, looking like misshapen rocks.

Her signing made me realise that the annual memorial to the atomic bomb in Japan completely misses out deaf people. The summer memorial is a big thing, people read and watch TV about it. But the Deaf woman’s story underlined the importance of getting the story of these Deaf Hibakusha, who were mostly 80, into the public domain before they died. In addition, as a Deaf person myself, I felt very strongly that their story had to be told. Thinking ‘the time is now’, I was lucky enough to get development money from the Artists’ International Development Fund at the Arts Council.

I used this money to return to Japan and film the Deaf Hibakusha, though two on the list had already died. The stories they told were very powerful – but then I had to ask myself how do I create art from this?

By now I had a different job as a BSL art guide so I wanted to combine my BSL art and digital skills with choreographing these stories. And that’s when I met a lighting and production designer called Jon Armstrong who works at The Guildhall, next to The Barbican, teaching lighting design and technology. I showed Jon my plans and he said, “Why not use Holo-gauze?” This was the answer, a key part of the show, making everything else possible.

A Holo-gauze is a see-through screen in front of the performer. It is very expensive, but it was money well spent. Normally a screen is behind, but here it’s in front – which is fantastic! It allows us to project the survivors telling their story in Japanese sign language, with English captions, with me behind. To avoid confusion there is only one set of signing going on at any one time but the captions are deliberately silent. The lack of a voiceover forces a hearing audience to use their eyes, making them aware of what it’s like to be Deaf.

Another piece of digital technology I use came from working with a Canadian man, David Bobier, whose company is called VibraFusionLab. David introduced me to a belt called a Woojer© Strap I wear that imitates the vibrations from music. But it took a sound engineer called Danny Bright to tweak my Woojer© so I could experience the high notes in music as they really are. Danny created a lowered vibrating soundscape for these notes. He also delayed the vibrations at times so that they were adapted to the rhythm of signing, which isn’t always as regular as music. To tweak the Woojer© this way took a lot of explaining. We had to be very clear with each other to make the right adjustments. It was also what I call a ‘Deaf-led’ process, meaning the team had to take their cue from me, reversing the usual pattern of Deaf people adapting to the hearing world.

Leslie: Can you describe Butoh and its influence on you, please?

Chisato: Butoh is a form of Japanese dancing that helped me to find a space inside, without music. It was founded by Tatsumi Hijikata in the 20th century. The dance helps to ‘tune in’ to a deep listening to what’s inside. I found Butoh also helped me to improvise.

Leslie: Could you expand on this quote from your website, please: ‘Our blackness is a gift’.

Chisato: This quote actually comes from the poem by Bridget Minamore that was performed with Kara Walker’s piece ‘Fons Americanus’ in the Turbine Hall at the Tate Modern. The sculpture is a 42 foot-high fountain, based on the Victoria Memorial in front of Buckingham Palace, depicting the history of slavery. As a BSL performer, I signed the poem that contained those words.

Leslie: Any final thoughts?

Chisato: One idea. Because BSL is both a language and an art, ‘Scored in Silence’ attempts to find a middle ground expressing itself in what I call ‘sign-mime’. So the piece uses gestures dictated by the visual imagination, rather than sticking all the time to the traditional BSL repertoire.

Next week I interview innovative cellist and passionate environmentalist Ailsa Mair Hughes

ABOUT LESLIE TATE’S BOOKS:

Part 2 of my interview with Mark Statman looks closely at Mark’s Latin American poetic influences, his life in Mexico and ends with an extract

I interviewed international poet and translator Mark Statman about Volverse/Volver, his 14th published collection. Mark, who has won national arts awards, is Emeritus Professor of Literary

I interviewed Lisa Dart, finalist in the Grolier, Aesthetica and Troubadour Poetry Prizes and author of The Linguistics of Light (poems, Salt, 2008), Fathom (prose

I interviewed writer Julia Lee Barclay-Morton about her experience of autism. Julia began as an experimental dramatist in New York, moving to the UK to

I interviewed Gillean McDougall from Glasgow, who edited the collaborative projects Honest Error (on Charles Rennie Mackintosh and his wife Margaret Macdonald) and Writing the

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

2 responses

Fascinating! Good luck to Chisato and I hope I might be able to see her work live at some point.

Yes, I’m hoping to see Chisato’s work live as well! ???