JANE BURN – POETRY AS HARD GRAFT, INSPIRATION, REACTION OR EXPERIMENT?

I interviewed poet & artist Jane Burn who won the Michael Marks Environmental Poet of the Year 2023-24 with A Thousand Miles from the Sea.

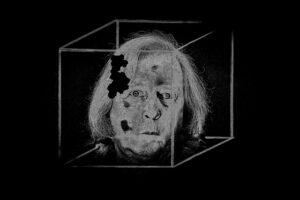

I interviewed photographer and theologian Werner Ustorf about his left-leaning ‘Agnostic Lutheranism’, his work as ‘Chair in Mission’ at Birmingham University, his writings about the Western-Aboriginal encounter in Central Australia and his impressions, as a British citizen born in Germany, of the UK today. The interview is illustrated by Werner’s black and white photographs.

Leslie: You were born in Germany where you say you were on the ‘Protestant Left’. What does that mean were you involved in, please? How did your life experience and upbringing lead you to adopt those views and actions?

Werner: It was the Federal Government in Bonn who called us ‘Protestant Left’. We were simply a group of journalists, church ministers and university lecturers arguing for the Third World to be released from capitalist terms of trade, for an end to Apartheid and for respect for the environment. When the Federal Republic military established a university-level institution in Hamburg, members of our circle published a manifesto claiming that a no to military service was ‘more Christian’ than becoming a soldier.

This all developed from 1945 when my birthplace, Hamburg, lay in ruins. I grew up in a context of devastation and in a family that was completely unchurched with very little cultural capital left to hang on to. I became a Christian to escape from the idols of the past and from the destruction of the present. During the ‘student rebellion’ of the late 1960s, I, like many others, tried to force professors to address the Nazi past and the new colonial war in Vietnam. One of them, a theologian, agreed, and I later did my PhD under his supervision on an African prophet and founder figure of an anti-colonial and anti-missionary church in the Congo. Later, when teaching at Birmingham University, I finished the other agenda and did a study on theology and mission during the Nazi period.

Leslie: Now, as a British citizen, what do you see as the cultural differences and similarities between the two countries?

Werner: Initially, I was shocked when I arrived in the UK (1990). I am not talking about Britain’s material culture that was a bit behind the Western European standard. I had been living in contexts of poverty in Africa and India and knew well enough that material culture and human wisdom were different and sometimes unrelated things. No, I was shocked because of the presence in the UK of what seemed to me to be an unbroken narrative of British nationalism. I was aware that critical scholarship had long debunked the mythology of empire, but in the public discussion there was hardly any evidence of self-criticism. Britain was also locked in a time-warp and mentally condemned, it seems, to repeat the D-Day landings over and over again. However, the failure to constructively deal with the past produced an obstacle for embracing the future. I am quite happy, therefore, that we are currently going through a process of re-evaluating colonial history.

Leslie: How did you research your book on the Western-Aboriginal encounter in Central Australia? What fresh insights did you gain about the subject?

Werner: The research was triggered by a visit to Australia in 2008. My wife, who is an artist, and I encountered the famous Aboriginal ‘dot paintings’ coming out of Central Australia since the 1970s. I found out that all these desert artists were baptised Christians, Lutherans in fact, but they used traditional patterns, not Christian symbols in their paintings. This was unusual, and I wanted to know why. The documentation of the very first encounter in the centre between Westerners and Aborigines in the 1870s are located in a mission archive in Northern Germany. A Lutheran archive in Adelaide has additional materials, and important anthropological data are held in the Strehlow Research Centre in Alice Springs. I spent time in all these places. It is important to state that all documents relating to the 19th and much of the 20th century were written by White people. The image emerging from this is therefore fragmentary, to say the least. For Black Australians, there is very little to celebrate on Australia Day. To them, the terms springing to mind are ‘invasion’ and ‘White flood’.

What did I find out? One example is this: the expression Dreamtime (Altjira) is an invention by White secular and colonialist anthropologists. They were not prepared to admit that ‘stone age people’ or ‘the most archaic’ form of human life could have abstract conceptions of the divine. They were just dreamers, mentally perhaps children. Freud’s theory on the origins of neurosis (see his ‘Totem and Taboo‘) are firmly based on this prejudice. The Bible in Arrernte, the local language, however, uses the term Altjira for ‘God’. There is now a Black, that is, an Aboriginal theology emerging that I would describe as a kind of dual religiosity – God, Altjira, can be encountered both ways, traditionally and the Christian way. And this may be the reason why Christian Aboriginal artists do not need to use Christian symbols.

Leslie: You held the ‘Chair in Mission’ at Birmingham University, UK. What are your criticisms of Christian Missionary activity, please? Are there practical examples you can describe of missionary activity that would stand scrutiny by indigenous and BAME critics?

Werner: Over two millennia there has been huge variety in how Christian mission has been understood and practised. The ‘colonial’ model is a highly-organised and strategic activity originating in the West and working hand in hand with Western capitalist expansion. Before that we had mission without and even against the empire. Just think of the Church of the East (the ‘Nestorians’ who had nothing to do with empire and colonialism) and its early mission to China, or forms of Black and Independent Christianity around the world! You will find that ‘western dominance’ is the last thing on their wish list. The centre of Christian gravity went south decades ago already. In fact, Christianity has become a mainly non-Western religion. Painting these new Christians with the old brush of Victorian mission does them a disservice. Many of the leaders of decolonisation went through Christian schools, and indigenous theology has appropriated Christ as one of them. I could go even further and say that much of indigenous pre-Christian culture has nicely survived inside the new Christian dispensation. Mission history and intercultural theology have produced rigorous research on all of this, but often ignored by the public in the West.

Leslie: What’s the story behind your self-description as an ‘agnostic Lutheran’ please? How did you come to this faith position?

Werner: I got baptised when I was fifteen. It was a deliberate decision, and the Lutheran understanding of God and Man is quite sophisticated and often attractive. But I soon discovered that faith, any faith, including no faith for that matter, rests on clay feet – in fact on imaginary feet. To make the point, knowing that one believes is fine, but believing that one knows is erroneous. The Christians I met as a young man were mainly of the second category, they misunderstood faith as ‘facts’. This made me leave the intellectual narrowness of the congregation. My question was if faith basically is a decision, something that might change over time, or something that could be plainly wrong, in other words, something that is historically contingent like everything else in our lives, then you have to let go any certainty. So, I remained a Lutheran, but one without certainty. One of my doctoral students wrote a marvellous PhD thesis with the title ‘faithful uncertainty’. That comes very close to what I mean. Interestingly, as an agnostic Lutheran I am very different from my wife who is an agnostic Greek-Orthodox. Agnosticism comes in all kinds of shapes.

Next week I interview poet, abuse survivor and LGBTQ truth-speaker Andreena Leeanne.

ABOUT LESLIE TATE’S BOOKS:

I interviewed poet & artist Jane Burn who won the Michael Marks Environmental Poet of the Year 2023-24 with A Thousand Miles from the Sea.

I interviewed ex-broadcaster and poet Polly Oliver about oral and visual poetry, her compositional methods, and learning the Welsh language. Polly says, “I absolutely love

I interviewed Jo Howell who says about herself: “I’ve been a professional photographic artist since I left Uni in 2009. I am a cyanotype specialist.

Poet Tracey Rhys, writer of Teaching a Bird to Sing and winner of the Poetry Archive’s video competition reviews Ways To Be Equally Human. Tracey,

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |