JULIA LEE BARCLAY-MORTON – YOGA, WATER AND REWRITING AUTISM

I interviewed writer Julia Lee Barclay-Morton about her experience of autism. Julia began as an experimental dramatist in New York, moving to the UK to

When I started Love’s Register, although the book covers 100 years of family relationships, it didn’t occur to me that I was writing a historical novel. So why didn’t I see what I was doing? Partly because I took it for granted that stories in past tense come from memory, and partly because characterisation (together with language) is my starting point. As a Modernist author I’m less driven by story, more interested in individual and group psychology. In fact, my characters often know more about what will happen next than I do. So to keep my creative freedom, I set out to write social history, avoiding known events or famous people.

For me, writing a book is the opposite of a planned essay. So I type something on screen, look at it, then delete or change by feel. The aim isn’t neatness, but something immediate – but also repeatedly tested, then chopped and changed in order to achieve closure at the end. It’s not about ordering material, but reflecting experience as it is, at the time.

Perhaps another contributing factor is my own messiness – I shove paperwork into a large cupboard, piled up any old way, and my desk is a tip – so I’m drawn to seeming incoherence, digressions, plus surprising twists of behaviour. And the timeline? It shifts a lot. Like an itch it’s something I keep coming back to…

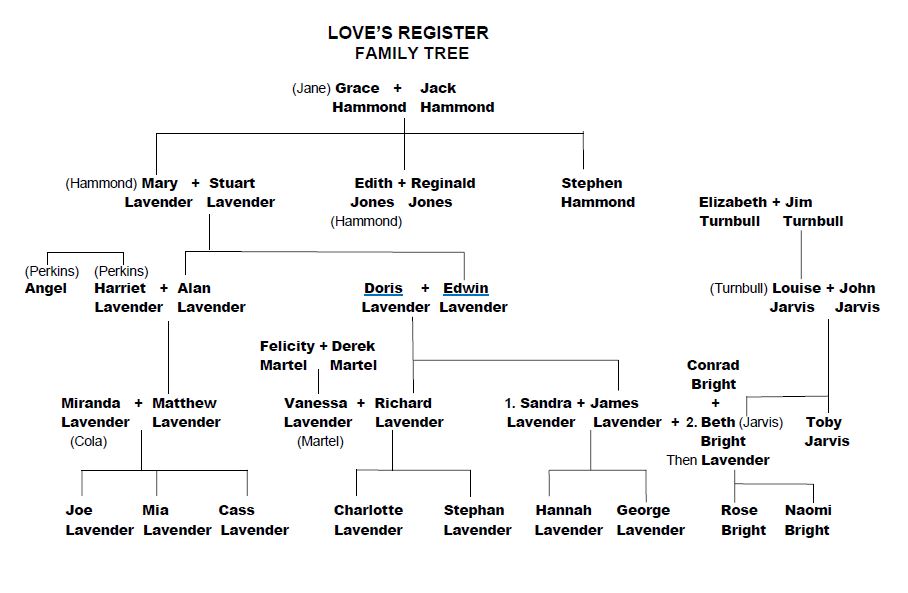

So I’m an unlikely candidate for a historical novelist. But I did link Love’s Register up in the end with a multi-generational family tree – pulled together later when the connections jumped out at me, rather than planned from the start. But perhaps that was possible because I’d put in cross-generational parallels in behaviour; also, I knew that some of my protagonists shared traits. It was still surprising when it fell into place. Writing history turned out to be more instant/situationist than tracing the slow march of time.

But given all that, how are the book’s historical eras marked?

It begins in the ‘60s with Matthew Lavender:

‘In the world of late-night talks, grouped around tables with coffee cups, candles and milk bottle joss sticks, or squatted on carpets with background drumming and acoustic guitars, Matthew listened closely, offering his insights with a sympathetic nod, a line saved up from Nietzsche or Blake and talk of us and them.’

So the timing of Matthew’s story is signposted by the 60s paraphernalia. But when we step back into the1920s/30s with his grandmother’s memories, or forward into the 21st century with the ‘climate kids’ Joe, Mia and Cass, it’s the idioms that mark the era.

Similarly, when the book reaches the radical fem ‘80s/90s the decade is signalled by phrases such as ‘The personal is political’, ‘a fish on a bicycle’ and a combative attitude to men:

“He has his uses,” Vanessa told Ruth on the day of the party as they plumped up cushions and turned out cupboards in search of glasses. “Richard’s a byword for action. I wonder sometimes if it’s in the genes, that kind of single-minded one-track thinking, like a runner near the tape. It’s all about getting it done, and PDQ.” “The male of the species.” Vanessa busied herself wiping down surfaces. “But it keeps them happily employed,” Ruth added. “Occupational therapy.” “Well, I suppose they like being useful.” “Yeah, like skivvies they need to be given tasks.”

In the final section the scenes move between Beth’s sheltered upbringing (with elements of her earlier thoughts/writing) and the extended adult challenge of her first date with her late-life lover James.

Picking out a letter, she unfolded it and spot-checked for phrases. The handwriting was large and filled up the page. In it she could feel an outline, a suddenness of presence, imagined in the flesh. A shoulder she looked over without being seen. It was as if she’d discovered a page from a half-finished diary; not real, of course, but quick and alive, present in the writing. He was out there somewhere, approaching. Again, she saw the house with its clothes racks, hangers, dressing gowns and books in bed. Feeling for the light switch, then thinking in the dark.

In the end, the narrative of Love’s Register is driven by personal experience, rather than by big historical events. If I’d started out as a historical novelist, I might have focused on a gap in the record in order to speculate, or studied an overlooked historical character to develop generic truths about human nature. Certainly, I’d have leaned towards the immersive rather than the literal side of hist-fic. So I wrote through the eyes of my characters, using some of what happened to me, and checking the historical detail later.

Fortunately, bar a few tweaks, the two matched up.

ABOUT THE BOOK:

I interviewed writer Julia Lee Barclay-Morton about her experience of autism. Julia began as an experimental dramatist in New York, moving to the UK to

I interviewed Gillean McDougall from Glasgow, who edited the collaborative projects Honest Error (on Charles Rennie Mackintosh and his wife Margaret Macdonald) and Writing the

I interviewed French writer Delphine de Vigan, whose book, No et moi, won the prestigious Prix des libraires. Other books of hers have won a clutch

I interviewed Joanne Limburg whose poetry collection Feminismo was shortlisted for the Forward Prize for Best First Collection; another collection, Paraphernalia, was a Poetry Book Society Recommendation. Joanne

I interviewed Katherine Magnoli about The Adventures of KatGirl, her book about a wheelchair heroine, and Katherine’s journey from low self-esteem into authorial/radio success and

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

4 responses

Hi Leslie, I found your thoughts on your book very interesting. I would not call your book a historical novel as it is the characters that lead and not the setting. The setting is a function of the characters. I would call your book literary fiction or a family saga, although family saga doesn’t really do your book justice.

Thank you, Robbie! Shall I send you some new interview questions?

Hi Leslie,

Thank you for that essay. It certainly sold your book to me.

Thanks, Frank! I hope you enjoy Love’s Register. 🙂 🙂 🙂