JULIA LEE BARCLAY-MORTON – YOGA, WATER AND REWRITING AUTISM

I interviewed writer Julia Lee Barclay-Morton about her experience of autism. Julia began as an experimental dramatist in New York, moving to the UK to

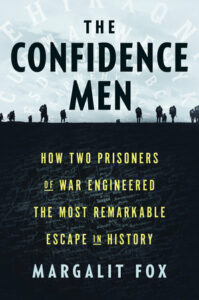

I interviewed one of the leading literary stylists in American journalism, Margalit Fox, about her 24-year-career at The New York Times. As a member of the newspaper’s celebrated obituary news department, Margalit has written the Page One send-offs for Betty Friedan, Maya Angelou, Seamus Heaney, Adrienne Rich, Maurice Sendak, and many more. Margalit has also written the obituaries of many of the unsung heroes of history, including the inventors of the Frisbee, the crash-test dummy, the plastic lawn flamingo and the bar code. She is the author of four narrative nonfiction books, with the newest, The Confidence Men: How Two Prisoners of War Engineered the Most Remarkable Escape in History, published on June 1 by Random House.

Leslie: Can you tell us, please, what led to you writing obituaries for the New York Times. What have you learned about the stylistic/emotional considerations and researching someone’s life? What’s been ground-breaking about your obituary writing?

MF: No writer plans on a career in obits: The child has not been born who comes home from primary school clutching a theme that says, “When I grow up, I want to be … an obituary writer!” I came to obits, as I have to most everything in my career, through a series of happy accidents.

I joined the New York Times in 1994 as an editor on the paper’s Sunday Book Review. It was a wonderful job—I was surrounded by smart people and great books—but I had trained as a writer and was pining for a career in which I could write my own stuff rather than cleaning up other people’s. After nearly a decade on the Book Review, I began to fear that when that far-off time came to write my own epitaph, the only thing it would say would be, “She changed 50,000 commas into semicolons.”

The catalyst came when I began contributing freelance advance obituaries to The Times’s obit department. These “advances” are the obits for the major figures—presidents, kings, queens, captains of industry, old-time Silver Screen stars—that are long and complex enough that newspapers don’t want to get caught short having to report and write them on deadline. So they are literally reported and written ahead of time—everything, of course, but the where and the when of the actual death—and they can hang around in the can for anywhere from days to decades.

I’d like to say that writing advance obits was a canny choice on my part, but it was purely a lucky one: One of the Book Review editors had moved over to become the head of Obits, and he inherited a woefully depleted stock of advances that it was incumbent on him to shore up—fast. So he recruited members of the Book Review staff, all of whom were marvelous writers, to write them. For me, this turned out to be a direct route to a full-time writing job at the paper, because historically Obits has been the job that no journalist wants, and the Obituary department of any daily paper has long been considered Siberia.

I’ve thought a great deal about the reason for this enduring stigma, and I can only conclude that the obituary beat has long been the victim of a self-fulfilling prophecy: Perhaps because of a primal fear of death, most journalists on any given paper wanted nothing to do with the Obit department. As a result, newspapers traditionally used the department as a dumping ground for their dead wood. Thus, the department produced much of that’s paper’s worst writing … and became even more stigmatized in consequence. And so it went, year in and year out, in an ever-widening spiral.

Happily, though, this stigma was a great help to me: When a Times obit writer retired in 2004, I applied for his job and got it, although I was largely unknown, because Obits remained the beat nobody wanted. Thus I became a cub reporter, on a big-city newspaper, when I was well into my 40s.

But as I’d learned from several years of writing advances (a truth of which, some 1,400 obits later, I am even more convinced), Obits is the best beat in journalism. Done properly, an obit is the most purely narrative form in any daily paper: The writer is charged with taking her subject from cradle to grave, and that gives the story a built-in narrative arc. What writer doesn’t love to be paid to tell the stories of interesting people, and what reader doesn’t love to consume them? As I’d also discovered, the longstanding association of obits with death in the popular imagination also turns out to be sorely misplaced: In an obit of, say, a thousand words, perhaps a sentence or two deals with the death; all the rest is the story of a rich and fascinating life. (An essay I wrote some years ago on the pleasures and pitfalls of being a professional obituary writer can be found here.)

Providentially, New York Times editors of the last 20 or 30 years have recognized—and wonderfully exploited—the enormous narrative potential of the obituary as a literary form. My former colleagues and I can authentically say that the New York Times Obituary Department boasts some of the very best writers on the paper if not in American journalism.

One of the things that’s been most pleasurable about writing obits for a paper like The New York Times is that while our obits, like every article in the paper, hew to impeccable journalistic standards—rigorously reported, written with complete fealty to the facts at hand—we’ve been encouraged to employ some of the techniques of literary writing (feature-style led paragraphs, vivid descriptions; connective tissue that makes the story flow; dialogue; and even, where appropriate, humor) to lift the story far above the plodding curriculum vitae that characterized obits of old.

A recent example from one of my advance obits illustrates the point. When I retired from the Times in 2018 to embark on life as a full-time book writer, I left about 80 advances in the can, which continue to give me a number of bylines each year. One of these concerned one of the most delightful characters it has even been my privilege to write about: Father Reginald Foster, an American scholar-priest who was for decades the Vatican’s chief Latinist. As a result of some careful instructions that I’d left for the editor who “put the top” on the obit when Father Foster died last year, we were able to open the piece this way:

“Reginald Foster, a former plumber’s apprentice from Wisconsin who, in four decades as an official Latinist of the Vatican, dreamed in Latin, cursed in Latin, banked in Latin and ultimately tweeted in Latin, died on Christmas Day at a nursing home in Milwaukee. He was LXXXI.”

I know from emails and social media that readers were tickled by that lead—and that it kept them reading the obit all the way to the end.

Leslie: How did you learn to write as ‘one the foremost explanatory writers and literary stylists in American journalism’? What is unique/characteristic about this tradition of writing? Who were your models/mentors – why them?

MF: Why, thank you! My 24 years at the Times, the last 14 of them in Obits, helped me immeasurably—a surprising thing in that I never set out to make a career on a daily newspaper. I firmly maintain that writers come into the world hard-wired for either long form or short form, and I although I didn’t decide on a writing career until I’d been out of university for a decade, it was clear to me from then on that I am a long-form writer in my bones.

My unorthodox journey to the writing life came about this way: In the early 1980s, after spending a miserable year in a Ph.D. program in linguistics in California, I decided to jettison all thoughts of an academic career and return to New York, where I’d been born and raised. I needed to find a job quickly, and I realized that my only marketable skills were that I could read and I could write. I spent the next decade in a series of low-paying, unfulfilling jobs in book and magazine publishing—my first bout with shoveling commas.

Toward the start of that decade, I met a young man who was plying a trade I had never considered. He was a freelance nonfiction writer, a profession of glorious enfranchised dilettantism that lets one read about anything, write about anything, ask questions about anything, think about anything and, if one is very lucky, get paid for it. (Reader: I married him.) After making what few strides as I could as a self-taught freelance writer, I entered the one-year master’s-degree program at the Columbia University School of Journalism in 1990, when I was just shy of 30.

I knew going into the program that I wanted to emerge as a long-form writer: My cherished models, from that day to this, are the great literary nonfiction stylists like Tracy Kidder and John McPhee. But in those years, Columbia was best known for preparing its graduates for newspaper careers, and my training there centered on the reporting and writing of short-form stories. The professor for my introductory reporting class, a wonderful woman named Robin Reisig, encouraged me to apply for a summer internship on a daily paper, to begin after I received my degree. “But I’m a long-form writer,” I howled in protest. “I don’t want to make a career in newspapers!”

Her reply set the course of my professional life for the next 30 years. “Go ahead and apply anyway,” she urged me. “Even if it’s not what you ultimately want to do, if you get an internship, it will be an invaluable experience.”

I took her advice and applied for—and got—a summer internship on New York Newsday, the late, lamented city edition of the venerable Long Island newspaper. I was the most geriatric intern their newsroom had ever seen (most are undergraduates, or new university grads), but as Robin had predicted, the experience provided the foundation for everything that followed: I wrote on deadline nearly every day and had the great pleasure of writing about the cultural scene—particularly classical music and Broadway theater—a thrilling beat to cover in New York. The vast portfolio of clips I built up that summer (and while continuing to freelance for New York Newsday in the years that followed) led directly to my being hired by The New York Times in 1994.

What was more, by the time I started work on my first narrative nonfiction book, Talking Hands, in the early 2000s, I’d come to realize that the short-form newspaper work of which I’d been so dismissive was actually the perfect training for the long-form work I craved—for what is a nonfiction book but a thousand-word newspaper story gridded up a hundred times? All of the structural devices that a book requires—the formal techniques that give a story its shape; keep it moving along nicely; and introduce the reader, bit by comfortable bit, to new concepts—are already fully present in any good newspaper article. It becomes, then, simply a question of magnitude … and endurance.

Having recently completed my fourth narrative nonfiction book, The Confidence Men: How Two Prisoners of War Engineered the Most Remarkable Escape in History, published by Random House on June 1 (publication in the UK here), I am more conscious of this fact than ever. Ultimately, as I tell young journalism students, if you want to be a long-form writer, the single best thing you can do is to spend at least a few years in the short-form world first. I wound up spending nearly three decades in that world, and even now that I’ve fully crossed over to the other side, it continues to stand me in good stead.

Next week, Margalit talks about her non-fiction books and what she has learned about writing.

ABOUT LESLIE TATE’S BOOKS:

I interviewed writer Julia Lee Barclay-Morton about her experience of autism. Julia began as an experimental dramatist in New York, moving to the UK to

I interviewed Gillean McDougall from Glasgow, who edited the collaborative projects Honest Error (on Charles Rennie Mackintosh and his wife Margaret Macdonald) and Writing the

I interviewed French writer Delphine de Vigan, whose book, No et moi, won the prestigious Prix des libraires. Other books of hers have won a clutch

I interviewed Joanne Limburg whose poetry collection Feminismo was shortlisted for the Forward Prize for Best First Collection; another collection, Paraphernalia, was a Poetry Book Society Recommendation. Joanne

I interviewed Katherine Magnoli about The Adventures of KatGirl, her book about a wheelchair heroine, and Katherine’s journey from low self-esteem into authorial/radio success and

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

2 responses

What a fabulous guest, Leslie. I love her writing, and I’m going to explore it in more detail. Good luck to Margalit Fox in all her future endeavours.

Yes, I was very lucky to get Margalit on my blog!