Part 2 MARK STATMAN: MEXICO AND THE POETRY OF GRIEF AND CELEBRATION

Part 2 of my interview with Mark Statman looks closely at Mark’s Latin American poetic influences, his life in Mexico and ends with an extract

In the second part of my interview with Margalit Fox, whose writing in The New York Times has helped develop a new literary approach to obituaries, I asked about her nonfiction books. They include Margalit‘s story of the race to decipher the mysterious Bronze Age script known as Linear B, The Riddle of the Labyrinth. That book was chosen as one of the hundred best books of the year by The New York Times and received the 2014 William Saroyan Prize for International Writing.

Originally trained as a cellist, Margalit holds bachelor’s and master’s degrees in linguistics from Stony Brook University and a master’s degree from the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism. Her work is prominently featured in The Sense of Style (2014), the popular guide to writing well by Steven Pinker, and Obit., the behind-the-scenes 2017 documentary by Vanessa Gould.

Leslie: Tell us about your books – their characteristic subject matter, point of view and the unique challenges you had to overcome in writing them.

MF: When I was a girl, my closest friend, Elizabeth, and I—she lived down the street from me in our little Long Island town—used to love to make treasure hunts, each taking a turn writing up a series of little paper slips that would lead the other, clue by clue, through one of our houses or yards or the woods around us, culminating in a little prize at the end. It wasn’t the prize—no more than a trinket—that spurred us on: It was the procedural thrill of working our way through the clues, like Theseus being led out of the labyrinth by Ariadne’s thread. (More than half a century on, Elizabeth is still my closest friend. Strikingly, also became a journalist.)

In recent years, I’ve come to realize that all my books are about treasure hunts: They are all nonfiction procedurals, following the step-by-step journeys of real people from states of unknowing or isolation to full knowledge and the liberation that comes with it. In Talking Hands (2007), I shadowed an international team of linguists as they studied a new sign language, sprung up spontaneously in a deaf Bedouin community, to learn what happens when the human mind makes a language from scratch. In The Riddle of the Labyrinth (2013), I documented the race to decipher a mysterious Bronze Age writing system, unearthed on Crete in 1900 and not cracked for more than half a century. In Conan Doyle for the Defense (2018), I turned my attention to a true-crime case: the wrongful conviction of a Jewish immigrant named Oscar Slater for a 1908 Glasgow murder he didn’t commit—and the private-detective work of no less a figure than Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, which set Slater free after nearly 20 years.

My new book, The Confidence Men, centers on a treasure hunt with the highest possible prize at stake: liberation from a prisoner-of-war camp. Step by step, the book chronicles the most remarkable confidence scheme ever conceived—and one of the only known con games to be played for good instead of ill. As I write in the introduction:

“This is the true story of the most singular prison break ever recorded—a clandestine wartime operation that involved no tunneling, no weapons, and no violence of any kind. Conceived during World War I, it relied on a scheme so outrageous it should never have worked: Two British officers escaped from an isolated Turkish prison camp by means of a Ouija board.

“Yet that scheme—an ingeniously planned, daringly executed confidence game—was precisely the method by which the young captives, Elias Henry Jones and Cedric Waters Hill, sprang themselves from Yozgad, a prisoner-of-war camp deep in the mountains of Anatolia.

“The plan seemed born of a fever dream. Using a handmade Ouija board, Jones and Hill would regale their captors with a tale, seemingly channeled from the Beyond, designed to make them delirious to lead the pair out of Yozgad. The ruse would also require our heroes to feign mental illness, stage a double suicide attempt that came perilously close to turning real, and endure six months in a Turkish insane asylum, an ordeal that drove them to the edge of actual madness.

“And yet in the end they won their freedom. …”

Leslie: What transferrable skills did you gain from your training as a cellist and linguist? What did you learn from ten years as a staff editor at the New York Times Book Review?

MF: The other thing I tell journalism students is that if you want to be a good writer, study music … or at least listen to a lot of it. My original training as a cellist has proved absolutely invaluable to me as a writer, for it has taught me to pay unremitting attention to tone, color, pacing and cadence, essential considerations if one wants one’s writing to sing. (A good many journalists, I’ve found, have musical backgrounds. At The New York Times—before lockdown—I’ve had the pleasure of playing with an in-house chamber-music group, the Qwerty Ensemble; the last piece we did was the Brahms clarinet quintet. I pine for the day when we can all play together again.) Reading a lot of good poetry—Yeats, Dylan Thomas, e.e. cummings, even some of the linguistic eccentrics like Gerard Manley Hopkins—is also a splendid asset.

I hold bachelor’s and master’s degrees in linguistics from the State University of New York at Stony Brook, and this education, too, has proved invaluable for a career as a writer: It has made it second nature for me to think about the logical consequences of every word choice—phonetic, metrical, semantic, syntactic. Of course, the reality of writing for a daily newspaper, under bruising deadline pressure, means that one seldom has the luxury of time to agonize over every word—if I’d done do so, I would have been out of a job long ago. Fortunately, the linguistics training has made much of the agonizing process automatic, ultimately costing me little time.

It is thrilling—if daunting—to realize that even the tiniest word can have resonant consequence for readers. An obit I wrote a few years ago, of Gregory Rabassa, the distinguished translator from Spanish and Portuguese, shows Rabassa grappling with this very issue as he sat down to translate Gabriel García Márquez’s masterpiece, One Hundred Years of Solitude. As I wrote:

“It is the translator’s lot to be afflicted with chronic, Talmudic agonizing — over sound, over sense, over meter, over meaning. With ‘One Hundred Years of Solitude,’ for instance, the torment began with the first word of the title.

“In Spanish, the novel is called ‘Cien Años de Soledad,’ with ‘cien’ meaning ‘100.’

“But there’s the rub, for the translator into English confronts an instant quandary: whether to translate ‘cien’ as ‘a hundred’ or ‘one hundred.”

“Professor Rabassa was an ardent believer in the aurality of text. To him, ‘a’ was an acoustic flyspeck, little more than a fleeting grunt. He chose the more durable ‘one.’ ”

As for my ten years at the New York Times Book Review, though I did find all those commas dispiriting over the long haul, I draw every day, in my book-writing life, on what I learned there. That work taught me what kinds of things work in published books, and what don’t; it taught me to prize writing (both in the reviews themselves and in the books under review) that is clean, spare and un-self-conscious; it taught me to choose my own book projects carefully, based on a sense of what the market will and won’t bear; and, perhaps most important of all, it taught me, as a writer of nonfiction, to source not only every quotation but also every assertion of fact: In my time at the Book Review, it became clear to me that it isn’t enough for a nonfiction writer simply to set a fact down in print; it is also absolutely essential that she state where she got that fact from in the first place.

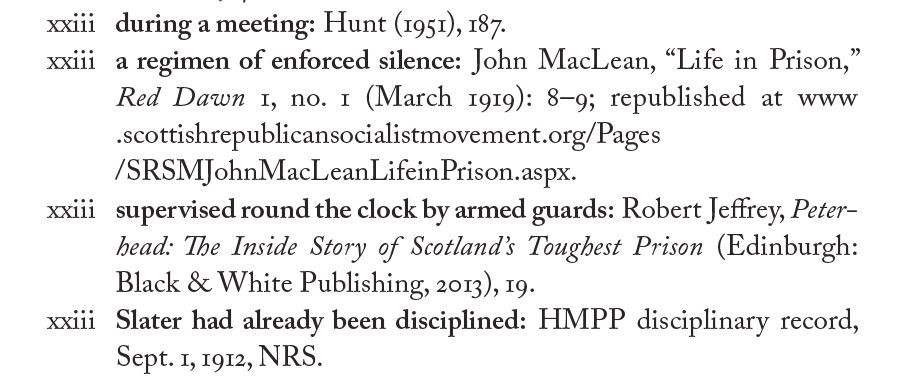

Every nonfiction book I’ve written, and every one I will write (I’m now working on Book No. 5), contains hundreds upon hundreds of bibliographic endnotes. The Confidence Men has nearly 2,000—no picnic to double-check and proofread, but it is a lineup that I trust will save me a world of second-guessing, finger-pointing and grief when the book makes its way into the world. Because I don’t want to impede the flow of the narrative line, all of my books use “trailing-phrase” endnotes, which keeps all those note numbers from appearing in the text itself, a sight that would conjure a dry academic tome in readers’ minds. In Conan Doyle for the Defense, for example, a sequence of endnotes keyed to an early passage about Oscar Slater’s incarceration reads this way:

If all this had appeared at the bottom of a single page in the main text—and with that text larded with note numbers, to boot—the book would be unreadable. Tucked discreetly in back, it offers me just as much protection while making for nice clean pages in the body of the book.

Leslie: For you as a journalist and essayist, what have been the most imaginary and subjective writing situations you’ve found yourself in? Where does fact end and authorship/judgement/fiction begin?

MF: I know just what you mean by the question, but I confess that the words “imaginary” and “fiction” always make me quail. I am—first, last and always—a journalist, whether the task at hand is a newspaper story of a thousand words or a nonfiction book of a hundred thousand. A journalist is charged with answering the same essential question as a historian—What happened?—and, like the historian, she must hew to the facts of the case with complete fealty. For me, “imaginary” and especially “fiction” suggest the making of stories, or parts of stories, out of whole cloth, and that, for a nonfiction writer, is the single most paramount taboo of all.

I feel so intensely about this that even the phrase “creative nonfiction”—an expression that is now, as the kids would say, “a thing”—sets my teeth on edge. Some years ago, I was interviewed for the journal Creative Nonfiction. The interviewer was a friend of mine, and we had a delightful time sitting for hours in one of my favorite New York coffeehouses (back when one could do that sort of thing) as she asked her questions. The interview came out fine, but I told her: “I’m afraid I just can’t get past the name of the journal. I don’t want readers to think that I spend my days making stuff up.”

But when it comes to employing the techniques of fiction in the service of nonfiction narrative … well, that’s another story. Because I was lucky enough to join the Times obit department in the Golden Age of newspaper obituary writing, I got a decade and half’s worth of practice in writing stories that did all the journalistic work of news obits—giving readers precise information on the who, what, where, when and why of things—without reading like the leaden obits of our parents’ day.

When I was in journalism school, I first encountered a disparaging phrase (said of any dry, clunky, old-style newspaper article but particularly applicable to old-style obits): “You can see the Scotch tape.” It was a quick-and-dirty indictment of stories in which each paragraph landed with a thud before the writer proceeded to the next thud, and the thud after that, and so on, with no connective tissue linking those paragraphs. My self-imposed goal, first as an obit writer and now as a book author, is to have no Scotch tape showing at all: I try to make whatever I write incorporate the needed factual material seamlessly, so that it flows like a silken stream. I want readers, after navigating a piece of mine, to have acquired all the information I set out to give them. But I also want them to have taken genuine pleasure in the journey.

Rather than thinking of what I do as “creative” or, heaven forfend, “fiction,” I picture my task as akin to that of an artist who works entirely with found objects. The facts of the story are my found objects, and from those I cannot deviate. But in assembling them into a cohesive work—and with the privilege of making choices about order, weight, tone, continuity and the like—I hope, on good days, at least, to be able to fashion them into something resembling art.

Next week I I interview indie musician and rock climber Maggie Braley, who composes her own songs and leads community singing.

ABOUT LESLIE TATE’S BOOKS:

Part 2 of my interview with Mark Statman looks closely at Mark’s Latin American poetic influences, his life in Mexico and ends with an extract

I interviewed international poet and translator Mark Statman about Volverse/Volver, his 14th published collection. Mark, who has won national arts awards, is Emeritus Professor of Literary

I interviewed Lisa Dart, finalist in the Grolier, Aesthetica and Troubadour Poetry Prizes and author of The Linguistics of Light (poems, Salt, 2008), Fathom (prose

I interviewed writer Julia Lee Barclay-Morton about her experience of autism. Julia began as an experimental dramatist in New York, moving to the UK to

I interviewed Gillean McDougall from Glasgow, who edited the collaborative projects Honest Error (on Charles Rennie Mackintosh and his wife Margaret Macdonald) and Writing the

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

2 responses

A marvellous interview. Thanks, Leslie, and thanks and good luck to Margalit Fox.

🙂 🙂 🙂