JULIA LEE BARCLAY-MORTON – YOGA, WATER AND REWRITING AUTISM

I interviewed writer Julia Lee Barclay-Morton about her experience of autism. Julia began as an experimental dramatist in New York, moving to the UK to

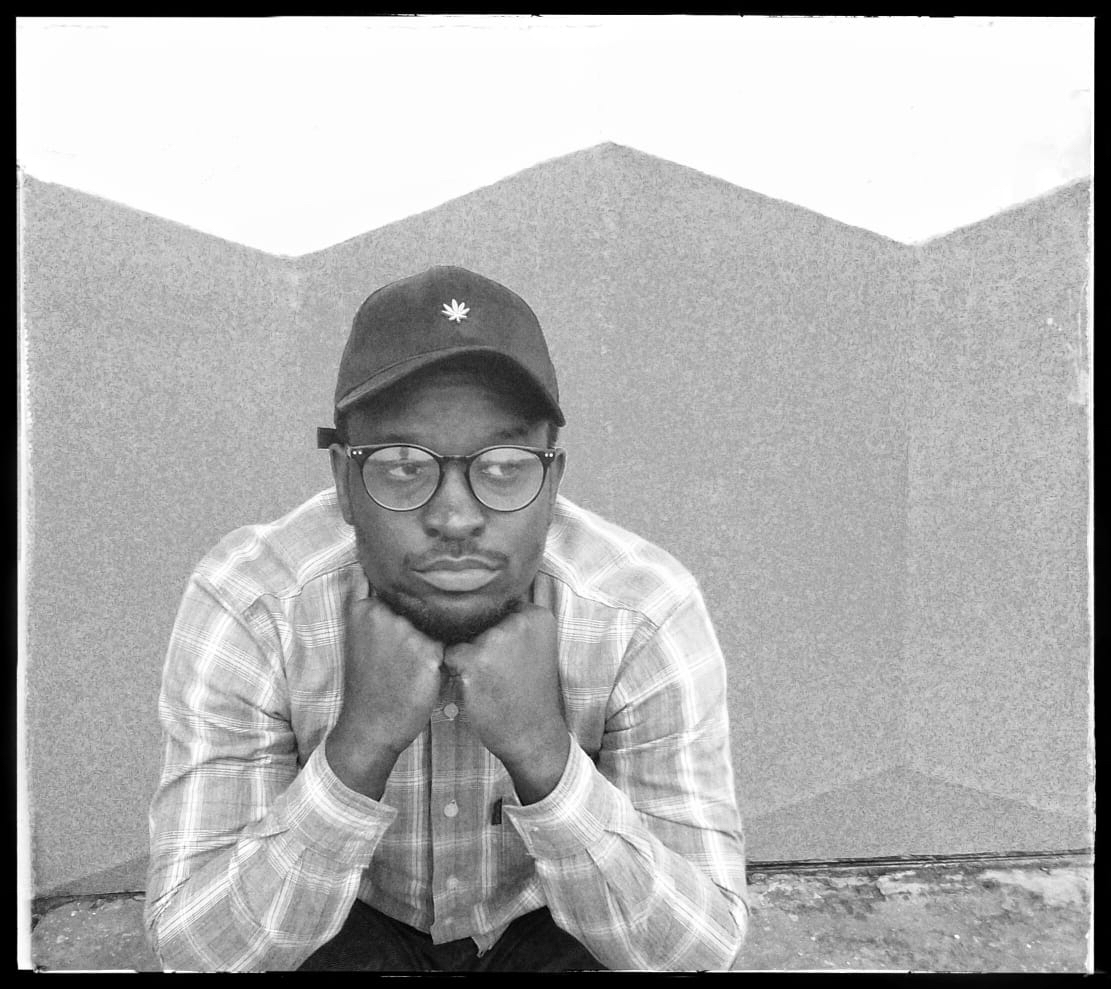

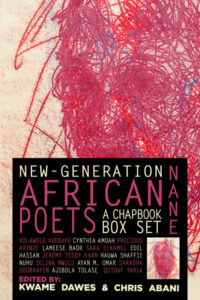

Jeremy T. Karn writes from somewhere in Liberia. His work has appeared in the 20.35: Contemporary African Poets Anthology, The Whale Road, Ice Floe Press, Lolwe, Feral Poetry, The Kissing Dynamite, Rigorous Magazine, and elsewhere. His chapbook (Miryam Magdalit) has been selected by Kwame Dawes and Chris Abani (The African Poetry Book Fund), in collaboration with Akashic Books, for the 2021 New-Generation African Poets chapbook box set.

today my mother cuts her hair low,

she looks old & tired.

i can see it from the silence in her eyes.

i am looking through her private things locked up & hidden,

maybe i will be lucky to see some childhood photos

of her dressed in t-shirt & jean, a big smile,

the medical kit box

she abandoned for my father,

or a love letter he wrote her

which i don’t believe he ever did.

when i think of how much i have aged,

i think of how much my mother has lived to keep me alive.

i want to see the history of how she gathered

herself from there to here

then into the silence i am looking at.

i swear, god knows how much

my mother has traveled inside herself,

everyday memories hold her hands into something deep

& the kettle beside her has learned

how to whistle her cries &

the songs wrecked in her throat.

today, my mother cuts her hair low & everything

has changed about her except

the grief she wears as hat.

Leslie: Tell us the story of what first triggered your writing.

Jeremy: Here’s the story: death, grief and longing are my major characters and my experience during the civil war is my minor character. The death of my uncle played a major role in me becoming a writer. In 2015, the 22nd of December, I lost my uncle. It was a hard situation for my family. Sometimes the fear of trauma is the beginning of one becoming a writer.

When my uncle’s burnt body was found, i stood over it, imagining his smile, his laughter and his small body. i stood there numbed in my skin and tears refusing to wet my eyes.

in 2016 when i began to think of my uncle, i found it difficult in expressing my thoughts to others and this began my story as a writer. i began to write about the things i longed to express.

Leslie: How do you recreate pain and grief through your poetry, and how does doing that connect with freedom? What are the core/seminal metaphors you use – why them?

Jeremy: As a child birthed during the heat of our country’s civil war, every childhood experience was engulfed with me and my friends running away from bullets. We were punished with a war we have no hands in. The experiences I had during the war with my family and what we are still going through help me to create pain and grief so uniquely in my poems. When I began writing back then, the pain and grief of the civil war kept pouring into me. Sometimes I got up from bed soaking wet with fear. But I realized that whenever I write about my pain and grief, I feel this small freedom. I think it’s a sin to stop writing about my grief and pain. To find salvation, I have to write about them, about my mother and her grief.

Leslie: Could you take us through the composition process for your poems moses: descendent of an ocean bender and Ode for My Mother?

Jeremy: I wrote the both poems the last week in the month of February this year. It was a Saturday morning and I sat down on the cold tile watching a documentary about Africans drowning in the Atlantic Ocean. I thought of my friend. My friend [. ] has been away from his family since he left his home hoping to reach Europe through the Atlantic Ocean. That morning I looked through my phone in search of his photo. I wanted to see it one more time so I can recognize him if it may appear in the documentary. moses: descendent of an ocean bender‘s first draft was submitted, I have no plan in reviewing it over and over before it lost its meaning. I wrote the poem and had no title for it. A friend from Nigeria suggested the title to the poem.

i have stopped watering my fear in losing you to an ocean,

& mama has gathered sea water in a jar & called it you.

Leslie: How has the war in Liberia affected you as a citizen and as a poet?

Jeremy: The day the war began again, I was at school. I remember my grandmothers and other parents running with their children.

I was seven years when the war ended. I had no memory of me chasing a kite into the clouds but rather bullets chasing me into a grave. My father was still away. The war affected me by taking away my childhood from me, my childhood friends who were buried in unmarked graves. We were too small for the war.

Leslie: What are the penalties and dangers of being queer in Liberia? How do LGBTQ+ people in Liberia cope with that? How has an understanding of that experience gone into your poetry?

Jeremy: Bullying and death threat are the penalties of being a queer In Liberia. LGBTQ+ cope with these things by living in fear and hiding their identities. You don’t come out in Liberia and expect someone to love you. It’s quite impossible for some Liberian to accept queer people in a homophobic society. When I began writing ” Potrait of a Liberian’s boy” I was a bit concerned of how it was going to be perceived by my readers in Liberia. I saw how people avoided the poem and talked only of the two other poems that were published with it. The poem was about my queer friend that’s afraid to come out. He knows the things that are out there for him. He’s scared to lose his life. [ ] loves who he is but our society says no to know. I think it is my duty to write about things that are important to him, things that make him believe he’s God’s son too.

Leslie: What’s distinctive/characteristic of your own poetic voice? How is it related to rule-breaking and rebellion?

Jeremy: The characteristic of my poetic voice is that it enables me to better understand my strength and weakness, and it has shaped me on how to employ my own voice to get the emotions in most of my poem. My poetic voice comes from my experiences. My experiences are difficult to be written about in Liberia so whenever I write about them I think of myself as a rebel, a rebellious son of this country. Sometimes our experiences force us to be rebellious.

Leslie: Who are the writers you’ve learned most from – why them?

Safia Elhillo, Romeo Oriogun, Pam Jacobs, Logan February, Billy Collins, and Tracy Smith. These are few of the many people I have learned most from.

Leslie: Given that your writing is very personal and often deals with difficult/traumatic experiences, how do you make sure it isn’t just therapy for you? What do you want the reader/listener to take away from your poems and the experience they represent?

Jeremy: I want the readers to take away from my poems the stories I am trying to tell in my poem. In Liberia there are some things we don’t really talk about, there are some things we are scared to speak about but in my poems without fear, i have tried my best to write about them. I want my readers to take away these things from my writing and know that these are the things I have experienced and am still experiencing as a citizen of my country.

Leslie: Tell us about your published/upcoming writing and how we can obtain copies.

Jeremy: I have few poems forthcoming in the coming months. Some are my works have been published by many amazing magazines like: Lolwe, 20.35 Contemporary African Poetry Anthology, Minute Magazine, Rigorous, Feral, and elsewhere. My chapbook will be out later this later but it’s now available for preorder this link: New-Generation African Poets: A Chapbook Box Set (Nane) – Akashic Books.

Next week I interview artist Bridget Bailey about her extraordinary nature-based hats and her textile flora and fauna, exhibited at Fortnum and Mason, Jagggedart and the Royal Academy.

ABOUT LESLIE TATE’S BOOKS:

I interviewed writer Julia Lee Barclay-Morton about her experience of autism. Julia began as an experimental dramatist in New York, moving to the UK to

I interviewed Gillean McDougall from Glasgow, who edited the collaborative projects Honest Error (on Charles Rennie Mackintosh and his wife Margaret Macdonald) and Writing the

I interviewed French writer Delphine de Vigan, whose book, No et moi, won the prestigious Prix des libraires. Other books of hers have won a clutch

I interviewed Joanne Limburg whose poetry collection Feminismo was shortlisted for the Forward Prize for Best First Collection; another collection, Paraphernalia, was a Poetry Book Society Recommendation. Joanne

I interviewed Katherine Magnoli about The Adventures of KatGirl, her book about a wheelchair heroine, and Katherine’s journey from low self-esteem into authorial/radio success and

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

2 responses

We know many people go through terrible experiences, but Jeremy’s poetry makes it so vivid… I hope he gets many readers and his message is heard. Good luck to Jeremy and thanks, Leslie, for bringing him to our out attention.

HI Leslie, Jeremy’s poem is very compelling. Many people in Africa suffer terribly from civil wars. I have a friend from the DRC whose whole family was murdered in front of him when he was a small boy. Very tragic. I hope Jeremy’s poetry reaches many readers.