SARAH ROSS-THOMPSON AND THE ART OF COLLAGRAPHED PRINTS

I interviewed artist Sarah Ross-Thompson whose exceptional Collagraphed prints use fabrics, lichen, porridge and string to create images of the dramatic Scottish Highlands where she

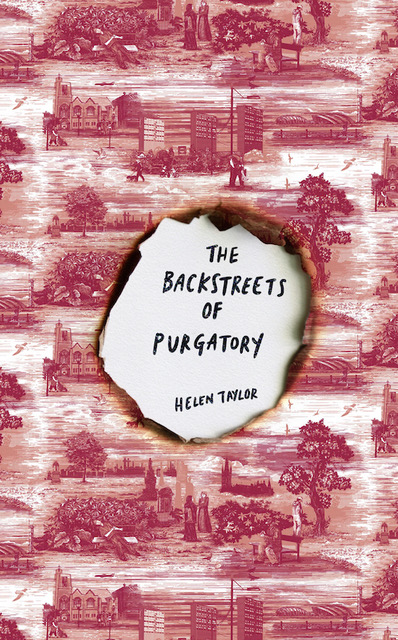

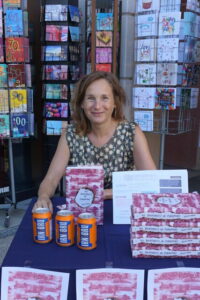

I interviewed novelist and poet Helen Murray Taylor who talked candidly about her mental health experiences and her related comic/serious debut novel The Backstreets of Purgatory. Helen‘s work has appeared in Boundless Magazine, Product Magazine, Poetry Scotland and as part of the Un(Mother) project at the Brighton Fringe 2021. She currently lives in France.

Leslie: Can you tell us about your ‘previous life’, training as a doctor and working as a research scientist?. How does your ‘rational’ past relate to the two major strands of your subsequent life – obsessive writing and life-threatening mental health issues? In what ways were the two states of mind always present? Does one state shade into the other or are they opposite sides of the same coin?

Helen: I studied medicine in Glasgow and worked as a junior doctor for a few years. That was back in the days when we worked crazy hours, over a hundred a week. It was brutal. The Art School connection comes from my student days, I guess. It was across the road and up the hill from my flat in Sauchiehall Street. We went there to see bands and to see the degree shows but sadly that’s as far as it goes. I’m not artistic in any way.

My first real encounter with mental illness came when I was a junior doctor, so I shifted sideways into research — infectious diseases and parasitology. I have PhD in the molecular biology of the parasite that causes malaria. It doesn’t come in particularly handy for my everyday life now that I’ve left research but you never know. Maybe I should write a novel about the shenanigans that go on in a research lab.

Until I started writing seriously, I believed in the divide between the rationality of science and the creativity of the arts but I’ve realised, in fact, that the type of skills and styles of thinking that I used for research science are exactly the same as those I use for writing. Both have a technical, logical side to them (for writing this means working on the craft, the thoroughness required for editing, the rigour of planning the structure of a novel etc; for research, refining practical skills, analysing results, planning the logical next step) but both require leaps of imagination, left-field ideas and originality to advance. That’s as true for research as it is for writing a novel. Strangely, I can almost feel the same part of my brain being physically stretched and tested when I’m immersed in writing as when I was seeking inspiration for my research projects. You need an investigative mind for both too. And to constantly interrogate your ideas. So, I would say that my rational state of mind and my creative state of mind are equally present and equally important. I like this idea of being both things at once. It’s a theme that comes up frequently in The Backstreets of Purgatory.

The mental health thing is different. It stopped me in my tracks. There’s a misconception that mental illness is associated with creativity — the myth of the mad genius. In reality, it’s pretty much impossible to achieve anything if you are as unwell as I became.

Leslie: Could you take us through what happened to you during your breakdown so the reader can get a picture of your symptoms & condition as well as how you were treated. What aspects of your experience found their way into your novel The Backstreets of Purgatory, please?

Helen: I had a history of depression from a fairly young age and post-traumatic stress disorder after involvement in a road traffic accident. The experience I describe in my essay Inside Ferguson House came a few years later, after lengthy fertility treatment, and a miscarriage of a baby conceived by IVF. It was devastating — both the loss of the baby and the fear, the likelihood, that I would never become a mother. The miscarriage coincided with starting a new job where I was desperate to prove my credentials (imposter syndrome plus plus plus). For a year, I struggled through grief, intense anxiety and depression with help from some amazing professionals — my GP, psychiatrist, community psychiatric nurse — while presenting a front at work, but the anniversary of my miscarriage hit me really badly. It got to the point where I didn’t want to carry on. I was admitted to hospital and completely stopped functioning. Didn’t eat, couldn’t sleep, lost dangerous amounts of weight, was suicidal and practically catatonic but at the same time convinced there was nothing wrong with me. I was sectioned under the Mental Health Act and eventually treated with electroconvulsive therapy. That hospital stay was fourteen months but it was just the first of several. I was under a hospital and then a community section for more than two years. The experience was horrific, cruel, funny, life-saving, farcical, profound, and changed me forever. My recovery was long and slow and very, very tough. I had to give up the work that I loved. I wasn’t capable of continuing with it.

I didn’t intend to write about mental illness in Backstreets. I deliberately tried to write something that wasn’t autobiographical in any way (to avoid the stereotype of the debut novel as a thinly disguised version of your own life) but I guess it is a theme that I can’t escape. My medical background helped with some of the details but being a patient on the ward and listening to other people’s experiences — of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, drug and alcohol addiction — gave me a much greater understanding.

Leslie: How did the other areas covered in The Backstreets of Purgatory come to you (e.g. Caravaggio, Glasgow, Irn Bru) and how do they fit into a novel with such a serious/funny subject?

Helen: I knew a bit about Caravaggio’s art from a couple of holidays to Italy — I was very proud of myself for being able to spot his paintings among the myriad of others with similar themes. They had an aura that made them stand out from the rest and which I found really affecting. I didn’t realise until later that he’d had such a violent life and that he’d murdered someone. I read a biography about him and decided he reckoned he was a hard man. A fleeting vision of him getting into trouble in a pub in Glasgow came to me and the novel developed from there. The contrasts and conflicts in Caravaggio’s life and art meant that he was practically a ready-made character (although the character in Backstreets is probably not at all how the artist himself would have liked to be portrayed). The city felt like a ready-made character too. Glasgow has so much personality, so many contrasts that echo those in Caravaggio’s work, so many defining characteristics. All I had to do was tap into a fraction of it.

Leslie: Your essay Inside Ferguson House treats some of the same material in a very different way. What are the similarities and differences between the two approaches?

Helen: Black humour is my way of dealing with tricky subjects whether they are fictional or narrative non-fiction. In terms of craft, the two are similar. I’m a visual thinker. I have to see the scene unfold before me before I can find the words to describe it. It’s the same for scenes from real life and from my imagination. In my essay, because of the nature of some of the material, I changed everyone’s names including my husband’s. It allowed me to distance myself from my own story and tackle it the same way I would treat any piece of writing. The hardest thing — the thing I haven’t mastered yet — is how to get beyond facile imagery and describe what such a catastrophic depression is really like. How destructive it is, mentally, physically, to yourself and to those around you. Clouds and black dogs don’t get anywhere near it, I’m afraid.

I guess the fundamental difference between the two approaches is the way memoir and fiction deal with the truth. The essay recounts true events (as much as anyone’s memory is an accurate account of the past, especially if it has had holes blasted in it by ECT). The novel disguises its truths behind the fiction.

Leslie: You have written about using a pseudonym and using accents and dialects in fiction. In both cases, what did you come up with as the dos and don’ts / pros and cons for their use?

Helen: Under any circumstances, writing dialogue can be tricky. Misrepresenting it is one of the quickest ways to turn off a reader. Authenticity is crucial but that doesn’t have to mean painfully accurate. As writers, it is as if we eavesdropping on conversations between characters, but we never write them exactly as we would expect to hear them. We drop the ums and ers, the stutters and the restarts that are scattered in natural speech, and pick the lines that develop the tension, or the good one-liners, or the parts that hint at undercurrents beneath the trivialities. If the language is strongly accented or in a pronounced dialect, the task automatically becomes more challenging. Should the dialogue be written phonetically, or as a watered-down version of what you heard, or written in standard English even if that wasn’t what was being spoken? Getting it wrong can take the reader out of the moment if they have to decipher the words or debate if the pronunciation has been accurately portrayed, or conversely, question the lack of an accent in a setting like Glasgow. Worse than that, if dialect is done badly, it can really appear like the writer is mocking the way a character speaks.

These were the types of issues I was grappling with as I tied myself in knots in early drafts of Backstreets, very aware of my own fairly neutral accent (north of England tinged with north east Scotland and the tiniest whiff of Glaswegian), and sensitive to the politics surrounding the language and dialects of Scotland: Standard English with an accent; Scots English with its own terms and pronunciations; Scots itself as a recognised minority language with its various regional variations. And what about spelling? By tradition Scots is an oral language and although there are plenty of written works to consult and several Scots dictionaries, for the moment there is still no absolute agreed consensus on the written form. I swithered between the extremes of standard spelling versus phonetic spelling and finally settled on something in between. In fact, I found syntax, word choice and cadence to be much more important in giving a sense of an accent than how the individual words were spelled.

I did consider writing under a male pseudonym or using initials, thinking that it might broaden my readership, but in the end, I decided it wasn’t a very feminist stance.

Leslie: Can you, from your experience as a driven writer, explain how writing can help, but how ultimately it transcends therapy?

Helen: It was a surprise to discover how much writing my novel helped my mental health. Although I’ve written about some of my experiences in the psychiatric hospital and I’ve recently been involved in a poetry project where we tackled head-on some of the issues around childlessness, I don’t tend to use writing as therapy per se and I didn’t even consider that writing the novel might be therapeutic in any way. When I began writing, I had already made big strides in my recovery but I still had a fair distance to go, even though I don’t think I realised it at the time. Writing was helpful because it completely occupied my mind. My characters came alive and filled my head so there was little room for anything else. I think my brain healed in the background while I was busy with the lives of Finn, Lizzi, Tuesday et al and frantically trying to maintain some level of control over them.

I love that moment when the characters become real. It has just happened with the novel that I’m writing at the moment. Their truths are revealed as if they are no longer anything to do with me, and that rather than invent or imagine them, my job is somehow to uncover them. I love it. Absolutely love it. That moment when you are lost in another world.

Next week I I interview Cheryl Hewitt about her mixed-media and stitch art, the discarded objects she collects and her ‘Mourning Dolls’.

ABOUT LESLIE TATE’S BOOKS:

I interviewed artist Sarah Ross-Thompson whose exceptional Collagraphed prints use fabrics, lichen, porridge and string to create images of the dramatic Scottish Highlands where she

Part 2 of my interview with Mark Statman looks closely at Mark’s Latin American poetic influences, his life in Mexico and ends with an extract

I interviewed international poet and translator Mark Statman about Volverse/Volver, his 14th published collection. Mark, who has won national arts awards, is Emeritus Professor of Literary

I interviewed Lisa Dart, finalist in the Grolier, Aesthetica and Troubadour Poetry Prizes and author of The Linguistics of Light (poems, Salt, 2008), Fathom (prose

I interviewed writer Julia Lee Barclay-Morton about her experience of autism. Julia began as an experimental dramatist in New York, moving to the UK to

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

4 responses

Hi Leslie This is an excellent interview. Mental health issues are very prevalent right now. Helen is quite right when she says that the creative experience for writing and R&D are similar. I’ve always said that progress requires great leaps of imaginative faith and the creative gene is prominent in the famous scientists and investors. Congratulations to Helen on her book.

Thanks, Robbie. Yes, Helen’s piece is mega-relevant! 🙂 🙂 🙂

Writing has wonderful healing powers. Thank you for this honest insight into your struggles because these words will help others.

🙂 🙂 🙂