Part 2 MARK STATMAN: MEXICO AND THE POETRY OF GRIEF AND CELEBRATION

Part 2 of my interview with Mark Statman looks closely at Mark’s Latin American poetic influences, his life in Mexico and ends with an extract

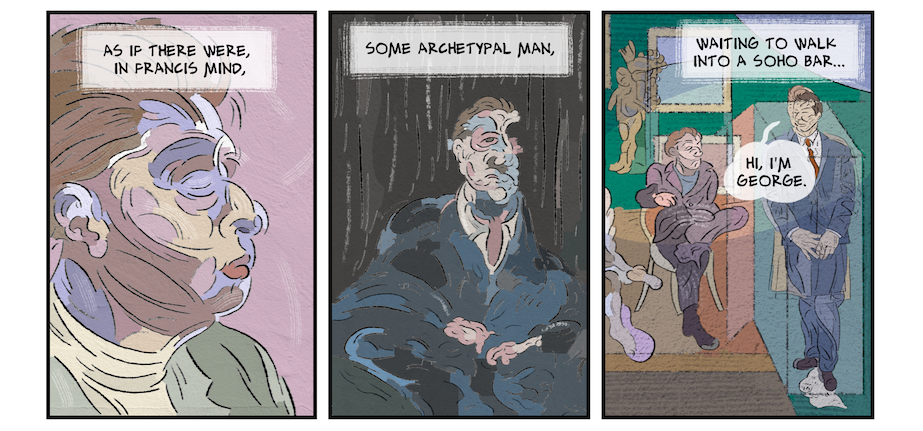

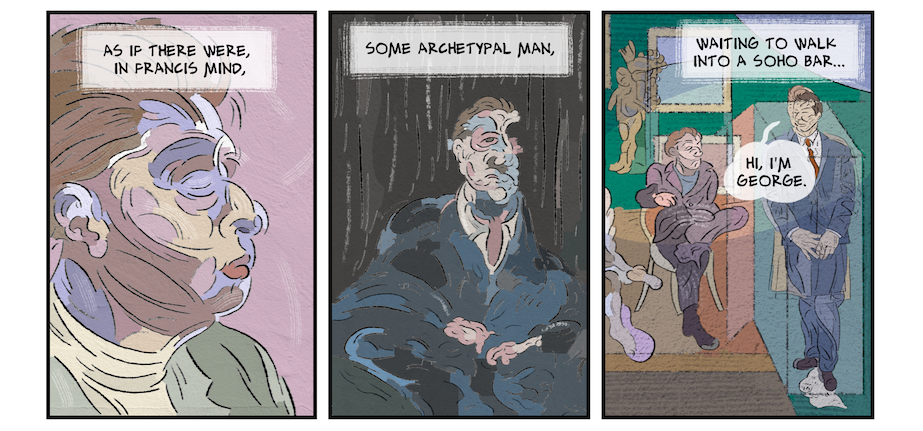

I interviewed graphic novelist Graham Johnstone who has created some exceptional visual stories based on the lives of famous painters. In the first part of his interview, Graham talks about how he put together graphic novels about Vermeer, Uccello and Francis Bacon. He also describes Tangled Tales, his non-linear comicbook, which has been turned into an interactive electronic artwork.

Leslie: Why does your recent work focus on famous painters and why did you choose, in particular, Vermeer, Uccello and Francis Bacon?

Graham: I feel I’ve always applied a fine art perspective to making comics. That’s to say I was more interested in pursuing my own creative interests, than meeting a client’s brief. Doing work about some of my artistic heroes seemed a way to connect my interests with a wider audience. I felt what I really had to offer was one artist’s (more modest) insight into other artists’ creation of timeless masterpieces.

Being trained initially as a visual artist, writing about documented lives, saved me having to invent stories and characters from scratch. For example, my Francis Bacon work-in-progress centres on 24 hours in Paris, as he faces a career high, and a personal low. It’s a powerful story, too unlikely to have been made up.

The specific subjects I’ve chosen are artists that continue to fascinate me, and in whom I see the same formal elements that attracted me to comics, particularly their evocation of time and motion. Renaissance painter Paolo Uccello is most acclaimed for his depiction of a battle, in three panels showing the beginning middle and end. So, like a comic, it’s a narrative in a sequence of images. He also shows sequences and stages of actions within each panel, for example, the massed army, their standard, their leader signalling the charge, and finally battle joined.

Vermeer and Bacon created the comics-like effect of ‘panels’ within a page by including pictures on walls and reflections in mirrors. Both also repeated motifs with variations, as I do in comics. Bacon painted sets of ‘three studies’ that I reflect in my page designs, with rows of three panels on my pages. These are visual techniques that interest me, and that I’m bringing to my projects.

However, I’m conscious that not every reader is so interested in these formal nuances, so I don’t start a project about an artist without seeing a compelling narrative. With Vermeer that’s an almost primal need for acceptance and recognition, with Uccello it’s over-ambition and the very real consequences of failure, and for Bacon it’s the tension between art and life, with the highest stakes.

There’s an example of both formal and narrative inspirations, in Vermeer’s painting Girl Reading a Letter. Reading this like a page (from top left to bottom right), it seems to depict the receipt of bad news. We see in sequence, a blood red curtain hanging over the girl like a threat, as she reads her hair seems to collapse from her head. Then we see the letter she is holding: bad news? The letter withers in her hand. Finally fruit (a symbol of life and fertility) spills from a tipped bowl. The painting has recently been restored to reveal a Cupid painting on the wall: so it’s a letter from a lover, or reporting his death, perhaps she is pregnant with his child (the spilled fruit). I think that’s a very powerful story. It may be that reading is unique to me, but hopefully it suggests I can channel great paintings into illuminating graphic novels.

Leslie: To begin with you spend months researching. What are your working methods (systematic? Juggling several projects? Intuitive? Driving yourself?) What books, exhibitions, artworks etc stand out from that process – why them (what was their personal impact)?

Graham: The first thing I had to research was approaches to biography, and the application of these in graphic novels. I’m a reviewer for The Slings and Arrows Graphic Novel Guide, and have now reviewed over thirty graphic biographies. Birth-to-death biographies tend to be hefty tomes even in prose form, and a graphic novel of that scale involves huge investment of time and money. Typex’s comprehensive Warhol biography Andy required several years of work, 550 pages and a multi-national publishing deal.

Some graphic biographies, like Freud by Corinne Maier and Anne Simon are extremely compact, covering his life and work convincingly in 60-odd pages. For example his relation with psychologist Carl Jung, moves from “you’ll be my heir” to “you’re in Oedipal rivalry with me” and ends in ejection from Freud’s house, all in a single page. The approach I’ve taken is to narrow the time-frame. My twenty page Uccello starts with him getting a commission, and ends with him completing his preparatory drawing. Most of my Bacon book takes place over 24 hours, though with a lot of memories and discussions of Bacon and his work.

Another question with biography is if, or how far to, venture into fiction. With Vermeer and Uccello, there is little evidence of their personalities or thoughts, so I opted to ‘interpolate’, to fictionally elaborate on documented events. For example I combined the factual explosion that levelled Vermeer’s home of Delft and killed its pre-eminent painter Fabritius, with the fictional, but perfectly possible, scene of Vermeer finding a wounded Fabritius amidst the wreckage.

Another approach to incomplete or unreliable sources, is to view the subject indirectly. We see Vermeer through the eyes of the (invented) model for his Girl with a Pearl Earring, in Tracy Chevalier’s novel of that name, and its film adaptation. My Francis Bacon book, centres on reported events around which there is ambiguity, so I tell the story from multiple partial perspectives of those around Bacon, from which the reader can piece together their own version.

My process from research to final work is very flexible. For a future work on Picasso and the Russian Ballet, I am having to research his various collaborators, like poet Cocteau, and composer Satie, though I concentrate on the period/ events I am covering. Discovering the Scrivener writing app, has really helped, as it lets me save all my notes, and ideas (along with photos, web pages, etc) in a single project. Often research will suggest a scene, and I’ll write it straight away. For example hearing that Bacon’s model broke into the studio and threw things around, let me reveal the current state of their relationship in a single dramatic scene.

I’ve been studying fiction writing as I’ve worked on the Bacon book, and as I’ve kept getting better I’ve reworked and expanded it. It is a pain to rework sequences I’ve already drawn, but I think it will result in a stronger book.

The last few months I’ve been concentrating on a drawing new opening chapter, but now that’s done, I’m taking some time to research and write the Picasso project. I’ll then continue writing that concurrently with drawing the Bacon book, so as soon as I finish drawing Bacon, I can start on Picasso. Producing a graphic novel is a lot of work, so I’m doing it for art and want to enjoy it. That means if I get up in the morning and don’t feel enthused about finishing yesterdays page, I pick up whichever one does enthuse me. In short, I’m methodical in theory, but much flexible in practice.

Leslie: Writing a script also takes months. What do you have to always keep in mind when writing scripts that will turn into a graphic novel? What are your daily routines/odd habits that help you in the process?

Graham: As you say, graphic novels are typically written in a format like a film script. However that’s based on someone writing for someone else to draw, and as a writer/artist I found it cumbersome. Now I’ll just draft the narration and dialogue in prose, paste that (a scene at a time) into my drawing programme (Clip Studio), and drag it between pages and panels. I’ll put the narration and dialogue into boxes or balloons, and descriptions (’Francis drops the paint tube onto the floor’) into each panel. I usually get the start and end of each page right first, and revise the rest until it works well as a page. I have my work critiqued in writers’ groups, and they’ve been happy to have submissions in this form.

As an artist, though, I don’t need all the visuals specified at the start. Sometimes there are key elements of stage management, like characters arriving and positions on the ‘set,’ but for more internal or poetic elements like characters’ reactions, I can usually come up with a more evocative visual at the drawing stage. A contorted Baconesque face expresses far more than than the words ‘George looks upset’. One panel had to suggest young Francis living rough, I had a sketch of him sitting on the steps he’ll later walk up to his exhibition. I scrolled through Bacon’s work and found a painting of a figure looking over his shoulder. That seemed to convey the vulnerability of that situation, and also prompted me to relocate the scene to an alleyway. This approach channels how Bacon himself worked, and keeps each day interesting for me.

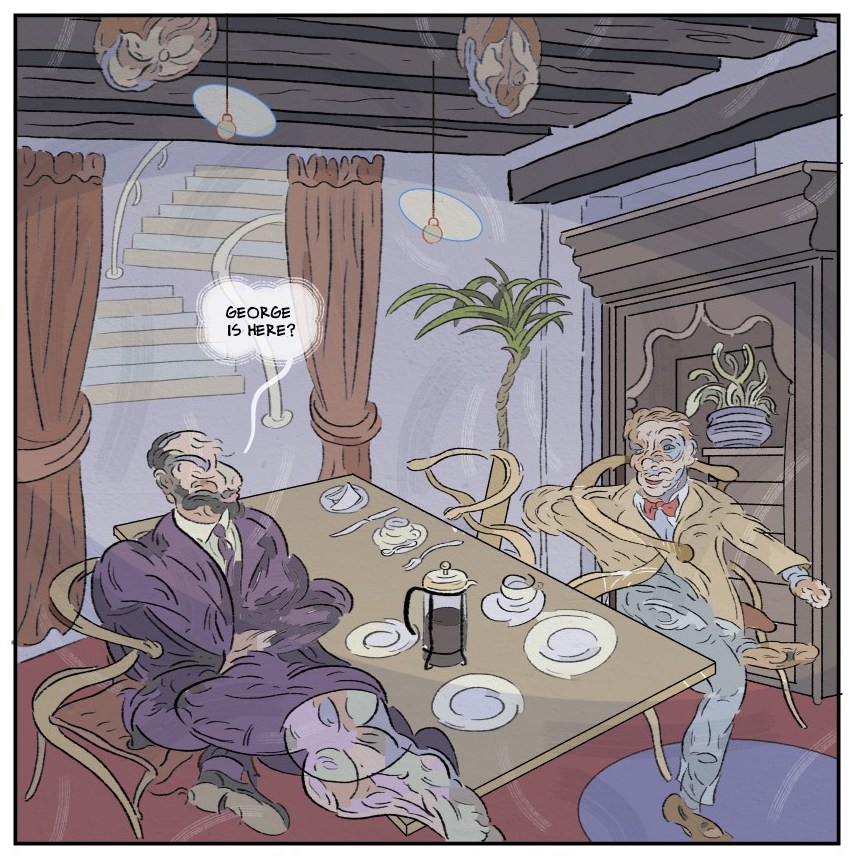

Leslie: Can you tell us what you’ve learned from creating Tangled Tales’ interactive comics? How have you developed the genre?

Graham: Tangled Tales consists of six sets of six panels, bound into six side-by-side booklets each containing a set of alternative first panels, second panels, and so on. This means it can be read in 6 to the power of 6 permutations. Now that I have a more theoretical grasp of narrative I can say that each opens with an orientation panel and a crisis escalates towards a new equilibrium, in the sixth panels. It’s a work that asserts its non-linearity. Even after having written all the six strands, it was a non-linear process of arriving at the final artwork. There are only 36 panels/drawings in the comic, but I must have drawn more than double that, as I kept finding new ways to wind the strands tighter together by progressively simplifying the drawings, repeating motifs and compositions.

Most of my work aims to convey subjective experiences, and linear thinking seemed unreal or an abstraction to me. Even now, decades later, having operated and led in organisations, I still find linearity something I arrive at circuitously, and with great effort.

It felt a great personal and artistic success to me to realise it, and turn it into a physical book. It may be the first of its type. One less happy lesson was that it was extremely time-consuming to make up the booklets, so a few years ago I arranged with a designer friend to create an interactive, electronic version. He did a brilliant job in replicating the interactivity. It’s published exclusively on iTunes, as none of the other ebook platforms could cope with the functionality.

I always had an intention to publish a Tangled Tales #0 that used the earlier versions of the panels, but that’s never reached the top of my to-do-list. Otherwise I’ve never thought of anything that added much after the original one, though there may be potential in the Ballet Russes story to have a strand from the perspective of each character.

The opening pages of the Francis Bacon graphic novel are most easily read on Pinterest. Tangled Tales is available to buy on Apple’s iBooks: search for ‘Graham Johnstone’ on the in-app store.

Next week, in part two, Graham Johnstone talks about his earlier artworks, his working methods an how he uses found objects.

ABOUT LESLIE TATE’S BOOKS:

Part 2 of my interview with Mark Statman looks closely at Mark’s Latin American poetic influences, his life in Mexico and ends with an extract

I interviewed international poet and translator Mark Statman about Volverse/Volver, his 14th published collection. Mark, who has won national arts awards, is Emeritus Professor of Literary

I interviewed Lisa Dart, finalist in the Grolier, Aesthetica and Troubadour Poetry Prizes and author of The Linguistics of Light (poems, Salt, 2008), Fathom (prose

I interviewed writer Julia Lee Barclay-Morton about her experience of autism. Julia began as an experimental dramatist in New York, moving to the UK to

I interviewed Gillean McDougall from Glasgow, who edited the collaborative projects Honest Error (on Charles Rennie Mackintosh and his wife Margaret Macdonald) and Writing the

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |